In his recent speech commemorating the 1965 Selma civil rights march, President Obama noted the nation’s paltry voter turnout rates:

If every new voter suppression law was struck down today, we’d still have one of the lowest voting rates among free peoples.

In this, he is absolutely right. But the cause of this is generally misunderstood. People too often suggest that the nation’s low voter turnout signals a character flaw among Americans, that they somehow do not care enough about politics or are simply irresponsible. But that’s not why voter turnout is relatively low in the United States. The cause is pretty simple—ours is one of the only democracies that requires people to register to vote. Voting, that is, requires that citizens give an affirmative “opt-in,” usually several months in advance of an election. In most other countries, voter registration is the job of the government, not the voters.

Voter registration was a product of Progressive Era reforms designed, quite overtly, to limit voter participation. In the late 1800s, it was widely believed among many journalists and political observers that voter turnout was too high. That is, party machines were turning out voters in some unsavory ways, sometimes paying people to vote, sometimes having them vote more than once. But even where specific electoral crimes weren’t occurring, many reformers were uncomfortable with parties encouraging the wrong sort of people—the uneducated, the illiterate, immigrants, freed slaves, etc.—to get out and vote.

Nineteenth century reformer Andrew White warned of “a crowd of illiterate peasants, freshly raked from Irish bogs, or Bohemian mines, or Italian robber nests, [who] may exercise virtual control,” even while they were “not alive even to their own most direct interests.” Charles Francis Adams Jr., the grandson of John Quincy Adams and great-grandson of John Adams, cautioned that “universal suffrage can only mean in plain English the government of ignorance and vice—it means a European, and especially Celtic, proletariat on the Atlantic coast, an African proletariat on the shores of the Gulf, and a Chinese proletariat on the Pacific.”

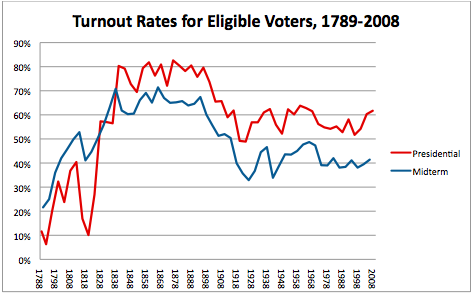

Voter registration laws passed at the turn of the 20th century were highly effective. Voter turnout plummeted, particularly among poorer and less educated Americans, producing the sorts of turnout biases we still see today. Of course, all these concerns and reforms in the cities paralleled the rise of the Jim Crow regime in the South, fundamentally disenfranchising African Americans through poll taxes and literacy tests.

The timeline below makes it pretty plain that those new laws were the cause of declining voter turnout. Americans didn’t suddenly become apathetic or irresponsible after 1900. New voter registration rules meant that if they wanted to vote, they had to register for the privilege of doing so several months before the election.

This is the context for understanding Oregon’s new law, which places the responsibility for registering voters back with the state government. Through the use of motor vehicle registration records, the state will look for people who are not registered to vote and then automatically register them unless those people decline. They will have the first opt-out voter registration system in the country in the modern era. This is a profound reform and a remarkable departure from much of the nation’s past.

It seems reasonable to expect that voter turnout will increase in Oregon once this law is fully implemented. As Jonathan Bernstein notes, however, this is occurring at a time when many states are making it more difficult to vote through the use of voter ID laws, limitations on early voting, lifetime voting bans for convicted felons, etc. It is certainly plausible that the next few years will see, as Bernstein suggests, several states (dominated by Democrats) making it easier to vote while other states (dominated by Republicans) continue to make it harder.

Laws that make it harder to vote may be anathema to good government and unbefitting a large democracy that fancies itself a model for the world. They are also entirely consistent with our history.

What Makes Us Politic? is Seth Masket’s weekly column on politics and policy.