East African elephants poached in the 19th century were lost in time, but a new study aims to map out their origins.

By Sukee Bennett

An elephant in Mikumi National Park, which borders the Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania. (Photo: Daniel Hayduk/AFP/Getty Images)

In the 19th century, wild African elephants roamed free of fences. The migratory mega-herbivores had vast impacts on the ecology and flora of East African habitats. But humans, in pursuit of ivory, hunted elephants relentlessly — and continue to do so. According to the Great Elephant Census, the savanna elephant population declined 30 percent in 15 countries between 2007 and 2014.

Scientists have had trouble tracing the geographic origins of most ivory from the 19th century, when the international trade intensified. But a new study, published last month in PLoS One, made headway in classifying the sources of historic ivory in natural history and museum collections. This led to an improved picture of 19th-century trade patterns, illustrating that most ivory came from East Africa’s tropical interior. Using the study’s methodology to analyze modern ivory, scientists can trace elephants most at risk of poaching or habitat loss today.

“Humans have sought after elephants for millennia for their ivory. It’s had a major impact,” said lead scientist Ashley Coutu, an archaeologist at the University of York in the United Kingdom.

The analysis by Coutu’s team relied on different chemical structures of each element, such as carbon and oxygen, called isotopes. These variations exist naturally, and are stored in both living and non-living things.

When animals eat and drink, they “incorporate varying amounts of each isotope and metabolize them differently,” Coutu said. By analyzing the levels of these isotopes preserved in tusks, hair and other tissues from elephants, scientists can trace their diets, habitats, and migration patterns across the East African landscape.

East Africa features strikingly different settings: lush coastal forests, dry open savannas, and tropical inland forests. Each dynamic habitat has a unique patchwork of trees and grasses, which normally carry different mixtures of the isotopes measured by Coutu’s team. Elephants aren’t picky eaters; they’ll munch on most vegetation. And as the pachyderms feed and drink from watering holes, they take up elements and their isotopes into their hair, teeth, and tusks.

In the study, the researchers analyzed carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and strontium isotopes from poached elephant tusk, bone, and tooth samples. Carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen contain clues about the climate, rainfall, and distance from the Indian Ocean where an elephant lived and ate. Strontium preserves hints of the geologic landscapes where an elephant roamed.

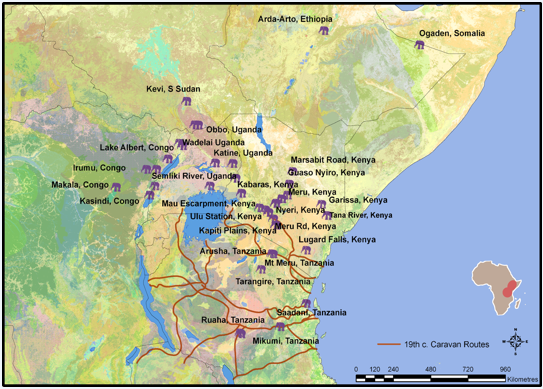

East African sites where the scientists determined many 19th- and 20th-century ivory trade elephants originated. (Map: Courtesy of Ashley Coutu.)

The team picked away at old billiard balls, piano keys, cutlery handles, and other ivory commodities from African, European, and American collections — sourced from about 100 elephants — and analyzed the remnants of tissue within.

“We could see patterns in the isotope data across the East African region that helped us characterize elephants to different habitats,” Coutu said. She added that many piano keys and ivory cutlery handles “had isotope values that matched elephants which lived in tropical rainforests” in East Africa’s interior, supporting earlier evidence that hunting eradicated elephants from the coastal areas of southern Kenya and northern Tanzania by the mid-1800s, pushing poaching inland.

But isotopes are only one tool; they are limited in what they can reveal.

“We’re never going to use these isotopes alone to map everything out,” said Matt Sponheimer, a biological anthropologist at the University of Colorado–Boulder who has conducted similar research.

But the study contributes to a growing body of data that helps scientists track and grasp the unique life history of the African elephant. The more scientists learn about this, the better they can work toward protecting modern-day elephants.

“This is something that began and was acceptable for so many years. If you look around and look at the poaching today, it’s in the same places,” said Nancy Cohn, a trustee at the Deep River Historical Society in Connecticut.

This story originally appeared at the website of global conservation news service Mongabay.com. Get updates on their stories delivered to your inbox, or follow @Mongabay on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.