This election will come down to roughly the same set of battleground states we’ve been watching for two decades, and the loser will likely win in excess of 47 percent of the two-party vote.

By Seth Masket

Senator Bernie Sanders delivers remarks on the first day of the Democratic National Convention at the Wells Fargo Center on July 25, 2016, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Photo: Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

We’ve heard about the ways in which the 2016 presidential election is breaking all the rules. The sharp differences between the nominating conventions in both tone and substance, Hillary Clinton’s surprisingly strong challenge from Bernie Sanders, the high unfavorability ratings of both major party candidates, basically everything about how Donald Trump became the Republican nominee and continues to campaign, etc. These departures from past cycles are striking and at least a little disorienting for those who follow presidential elections. But perhaps one of the more interesting things is how similar to past elections this one may end up being.

Judging from the coverage surrounding the recent conventions, one might think that some sort of party re-alignment is in the works. Conservative pundits noted that Democratic Party leaders seemed to claim some of the themes and optimism of Ronald Reagan, while the Republican convention was almost entirely organized around Trump’s message that the nation was doomed unless he was unleashed to save it. And the Republican convention was perhaps most notable for those who didn’t attend it, including both Presidents Bush, John McCain, Mitt Romney, Jeb Bush, and Marco Rubio. And, of course, one of that convention’s most memorable moments was Ted Cruz’s conspicuous failure to endorse his party’s nominee.

The implication was that the Republican Party coalition may be cracking up, even if perhaps only temporarily. Is it?

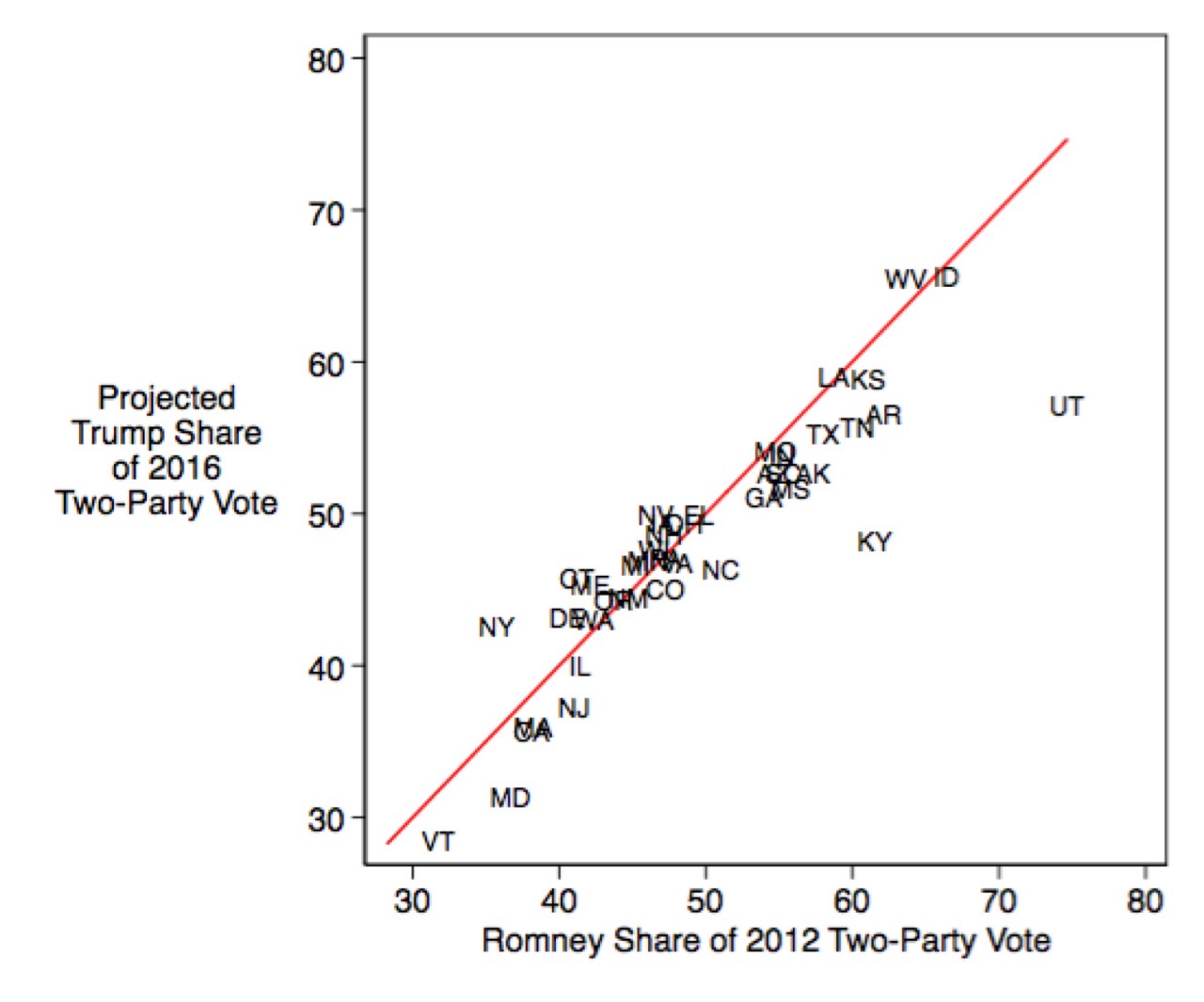

One way to examine this is to compare Trump’s polling in the various states with the performance of previous Republican presidential candidates. (I’m borrowing this analysis from a paper done by political scientist David Karol earlier this year.) The chart below compares Romney’s share of the two-party vote in 2012 with Trump’s expected vote share given state-level polling in 2016. The red line indicates Romney’s level of support: if a state appears above that line, then Trump is out-performing Romney.

To a remarkable degree, the states are sticking very close to the line, and the two variables correlate very closely. In other words, if you know how Romney did in a state four years ago, you can come very close to predicting how Trump will do there this year. Apart from some notable Trump under-performances in Utah and Kentucky, we’re seeing very little evidence of a Republican Party crack up. The coalition seems to be holding.

Now, there are a number of important caveats in this analysis. For one, all states are not polled equally. Some of the less competitive states haven’t been polled in several months, while the swing states were polled very recently and repeatedly—so are likely more accurate — but were polled in the middle of Trump’s post-convention surge.

Also, the figure above uses estimates of the two-party vote, which means that undecided voters are ignored. In some states, there are still quite a few undecideds (including 37 percent of Utah’s electorate). They may end up breaking evenly between the major party candidates, but that’s not obvious at this point. Perhaps most of those are Republicans who can’t quite bring themselves to vote for Trump. Perhaps they’re Trump supporters who don’t want to admit it to pollsters. Perhaps they’ll end up supporting the Libertarian or Green Party candidates. It’s hard to know right now.

But the graph above suggests two important things. First of all, the alignment between the parties seems to be holding this year. More traditionally Republican states are more supportive of Trump. This just reminds us that Republican voters are rallying to Trump, not quite, but almost, as much as Democrats are rallying to Clinton.

Second, this election will likely be relatively close. You may quite legitimately believe that Trump’s behavior, or Clinton’s association with political scandals, should mean that the electorate will overwhelmingly reject him or her. But Clinton will be sustained by areas of traditional Democratic strength just as Trump will be backed in the Republican strongholds. This election will come down to roughly the same set of battleground states we’ve been watching for two decades, and the loser will likely win in excess of 47 percent of the two-party vote.

In the end, this very weird election cycle will probably end up looking like a pretty normal one in the election returns. Whether that’s more comforting or more disorienting is another issue.

||