A barn near Jennings, Louisiana. (Photo: polymerchemist/Flickr)

Kristen Gary Lopez’s grandmother still kept the newspaper clippings stored in a box. When investigative journalist Ethan Brown met her at her home and they sat down at her kitchen table, she got them out. “And she’d laminated them,” Brown told me, “which you can see anybody doing.” In March of 2007, the body of Kristen Gary Lopez was found in Jefferson Davis Parish, Louisiana. One year later, her cousin Brittney Gary would also be found.

But what stuck with him wasn’t the clippings, Brown suggested. “She said, ‘You can have these if you want.’ And I said: ‘I don’t want them, they’re yours! I’m not taking your memories.’”

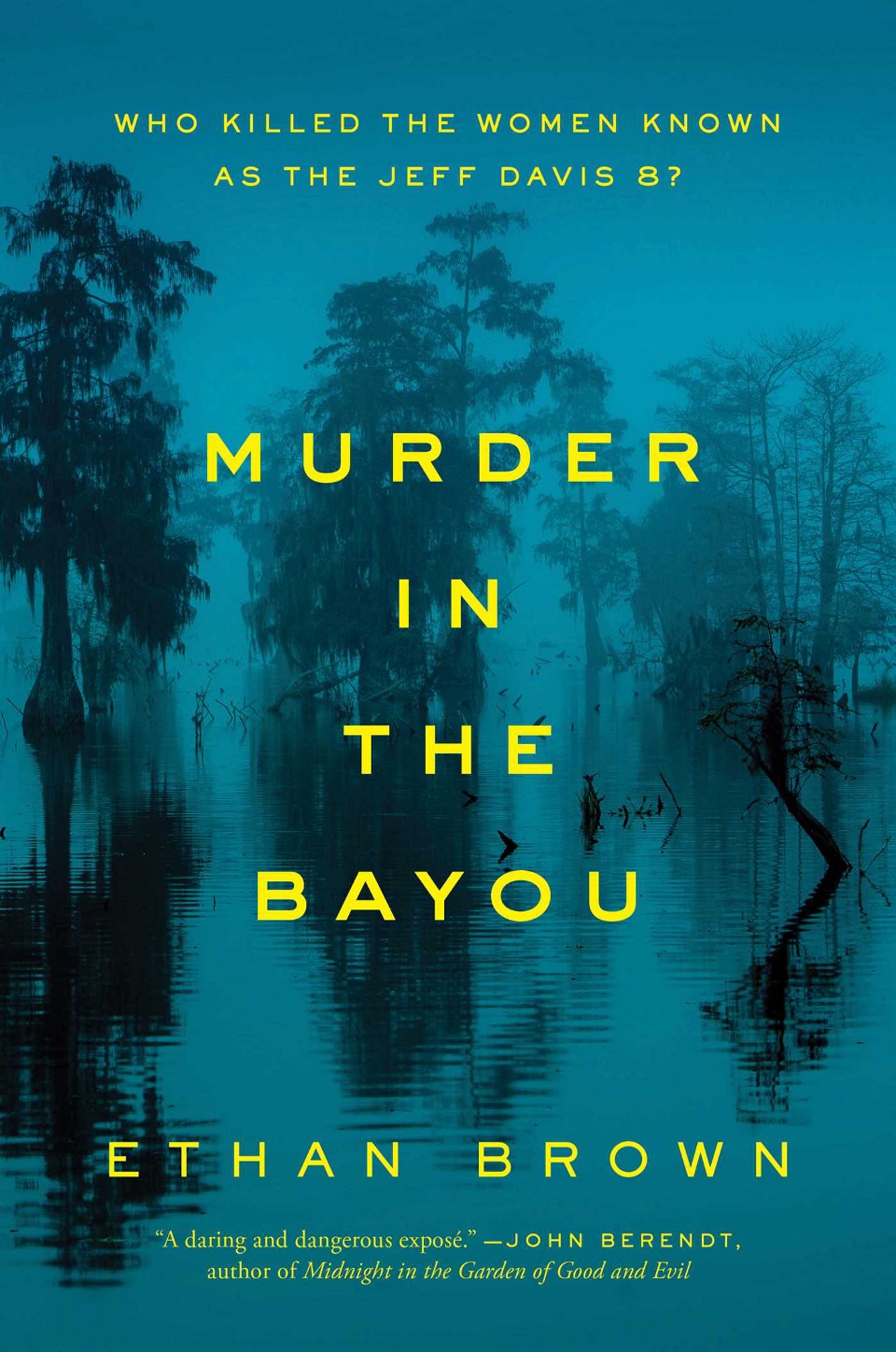

Brown’s new book Murder in the Bayou: Who Killed the Women Known as the Jeff Davis 8? traces the intersecting lives of eight Louisiana women, including Kristen and Brittney, now known as “The Jeff Davis 8.” Between 2005 and 2009, their bodies were discovered “around the swamps and canals that ring Jennings, a staggering body count for a tiny sliver of a town of about 10,000,” Brown wrote in the 2014 investigation for Matter that inspired the book. Now, seven years after Jefferson Davis Parish law enforcement announced its suspicions that a “common offender” — a serial killer — was targeting sex workers in their small community, their killings all remain unsolved.

For a public primed to view sex workers as characters in a “special victims” serial drama, a serial killer marks both the beginning and end of the story.

Local and national press underscored the women’s links to the area sex and drug trade. Brown fills in their stories with care, drawing on deep sources in Jefferson Davis Parish and a trove of public records he obtained over four years. Another portrait of the women is clear from his work: They knew one another intimately. They had worked together out of the same motel, the Boudreaux Inn, where police made near-daily arrests. Brown also reveals that lives of these eight women — Loretta Chaisson, Ernestine Patterson, Kristen Gary Lopez, Whitnei Dubois, Laconia “Muggy” Brown, Crystal Zeno, Brittney Gary, and Necole Guillory — all crossed, sometimes intimately, with local police.

Necole Guillory was “at the very center” of the scene, Brown writes. She was killed in August of 2009, the last of the Jeff Davis 8. Not long before her death, she told her mother Barbara Guillory not to bother with a cake for her birthday that year: “Momma, it doesn’t matter,” recalled her mother to Brown, “I’m not gonna be here.” She also told Brown that Necole had confided in her: “it was the police who were killing those girls.”

Brown’s investigation doesn’t make that direct accusation. What he does is show what information law enforcement had, when they had it, and what they didn’t do. A special task force comprised of state and federal law enforcementhad been convened in 2008 to solve the killings. Nearly one year before Necole Guillory’s death, a witness told the task force that a client she shared with Necole told her Necole “felt that she might be the next victim.”

“This highly specific tip received no follow-up by the task force — a lapse that may have proved fatal,” Brown writes.

Later, Necole’s boyfriend told the same task force that she said she had sex with Jefferson Davis Parish jail warden, Terrie Guillory, so he would release her from jail. Another task force witness alleged, according to a report Brown obtained and shared with me, that Terrie Guillory’s name “came up often in reference to having sex with prostitutes in Jefferson Davis Parish.” One of those women, according to another witness, was Loretta Chaisson, the first of the Jeff Davis 8. That jail warden, Terrie Guillory, was also a cousin of Necole’s.

It was after Necole’s death that Jefferson Davis Parish Sheriff Rickey Edwards, at a task force press conference, announced that, “It is the collective opinion of all agencies involved in this investigation that these murders may have been committed by a common offender.”

The “common offender” theory pushed by Jefferson Davis Parish law enforcement is at once horrifying and easy to believe. For a public primed to view sex workers as characters in a “special victims” serial drama, or who might only read the names of sex workers in the paper once they are dead, a serial killer marks both the beginning and end of the story. It is also not uncommon for serial killers who prey on women who sell sex to go undiscovered for decades — like Gary Leon Ridgway in the Pacific Northwest, who infamously claimed he targeted sex workers precisely because he thought “I could kill as many of them as I wanted without getting caught.”

But Brown illustrates how Jefferson Davis Parish law enforcement’s serial killer theory has served to deflect attention from its own troubled investigation. “For years,” he writes, “it has been easy to see the slain sex workers as simply the victims of, as Sheriff Edwards has repeatedly and dismissively told this media, a ‘high-risk lifestyle.’” This kind of victim-blaming is still socially acceptable when the victim is a sex worker. But to put the blame on “lifestyles” is quite another thing when police were also a substantial part of the victims’ lives.

If local law enforcement and the task force have provided few answers, local media hasn’t, either, even after the book’s publication. Speaking with me around the eighth anniversary of the launch of the task force in Jefferson Davis Parish, Brown told me he hoped some follow-up reporting would appear. He said he has offered to share with reporters the public records he’s obtained. So far, what’s most interested the press hasn’t been reporting on the women whose killings are still unsolved, but about one Louisiana politician’s lawsuit against Brown and his publisher.

A September 2016 Washington Post story used his race for the United States Senate as a hook: Louisiana Republican Representative Charles Boustany, sought the seat vacated by Senator David Vitter, and contested by former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard David Duke, along with 22 other candidates. Brown reported in his book that a field representative for Boustany, Martin Guillory (no relation to Terrie or Necole), was a co-owner of the Boudreaux Inn, frequented by all of the Jeff Davis 8 victims. The Post story included what three women in Brown’s book told him: that Boustany had been a client of sex workers, including some of the Jeff Davis 8. (Brown did not allege that Boustany had anything to do with their deaths.)

Two of these women, one of them an unnamed former sex worker and another referred to as Boustany Witness A, told Brown they were interviewed by the special task force. On that task force was “Edward W. Reed, a senior resident agent at the FBI’s Lake Charles Office,” Brown said. When Brown asked Reed in August of 2015 about the meeting with Boustany Witness A, he “refused to confirm or deny such a meeting occurred.”

In May of 2016, Boustany’s communications director replied to Brown’s questions about the case, including the claims made by these women: “Dr. Boustany had no prior knowledge of Martin Guillory’s prior involvement at the establishment you mentioned … never had any contact with any of the eight victims you mentioned … never visited that establishment.” But it was only when Boustany’s wife defended him from the allegations, which led his challengers in the Senate race to bring Brown’s reporting into the election and the attendant news cycle, that he fired former Boudreaux Inn owner Martin Guillory from his staff. Nearly one month later, Boustany announced a lawsuit against Brown and his publisher, Simon & Schuster.

“This phrase, ‘we can’t independently confirm X,’ or ‘we can’t independently confirm Y,’ appears in multiple pieces about my book. Yet I know for a fact that no effort has been made to independently confirm X or Y.”

In October, the Times-Picayune editorial board endorsed Boustany for senator. “During the campaign, an author claimed in a new book that Rep. Boustany had been a client of prostitutes in Jefferson Davis Parish,” they wrote. “The accusations were based on anonymous sources. The author declined to provide a Times-Picayune reporter with the names of the women to independently verify the allegations.” While three women who alleged Boustany was a customer of sex workers are unnamed by Brown’s book, claims about his former field representative Martin Guillory are sourced from public records.

The Boustany claims are not a pivotal event in the book: They come after an avalanche of other statements from named sources, alleging law enforcement inaction and misconduct. Still, an October Advocate story on Boustany alleged that “the chapter on Boustany relies entirely on unnamed sources.” This is untrue — Brown details the public property and law enforcement records he used, as well as his having made those records available to Reed at the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

The Advocate also reported that Martin Guillory found a new job — on the campaign of a local Republican who wanted Boustany’s seat. According to the paper, his new boss “said Guillory is a well known and skilled political operative with deep contacts in Acadiana’s African American community.”

In a case marked by official deflections, this feels like more of the same. Brown, who wants reporters to dig deeper into this case, was frustrated to see stories overlooking what he had reported. “This phrase, ‘we can’t independently confirm X,’ or ‘we can’t independently confirm Y,’ appears in multiple pieces about my book. Yet I know for a fact that no effort has been made to independently confirm X or Y,” Brown said. “You cannot write that sentence without having made an effort.” It’s for his reporting — or for one subject’s annoyance with it — that Brown and his publisher were sued. (The suit was dropped by Boustany in December, after he lost the November runoff and, with it, his bid for the senate.)

The whole investigation started, Brown told me, before he had an assignment, just knocking on doors. One day in July of 2011, he arrived at a home that had become a crime scene. A man Brown had just encountered the night before was shot to death. Police, Brown said, left his home unsecured, and he watched as other men removed items. People told him that this kind of thing was not unusual in Jennings. “That’s the thing that made me want to write about this.”

One of the people who most strongly emphasized that such occurrences “were just life in Jeff Davis Parish,” he met after he knocked on a Lake Arthur trailer door. It was Barbara Guillory, the mother of victim Necole Guillory, who answered. “Why don’t you try living here in Jennings for a while,” Brown recalled her saying, “and you’ll see that.”