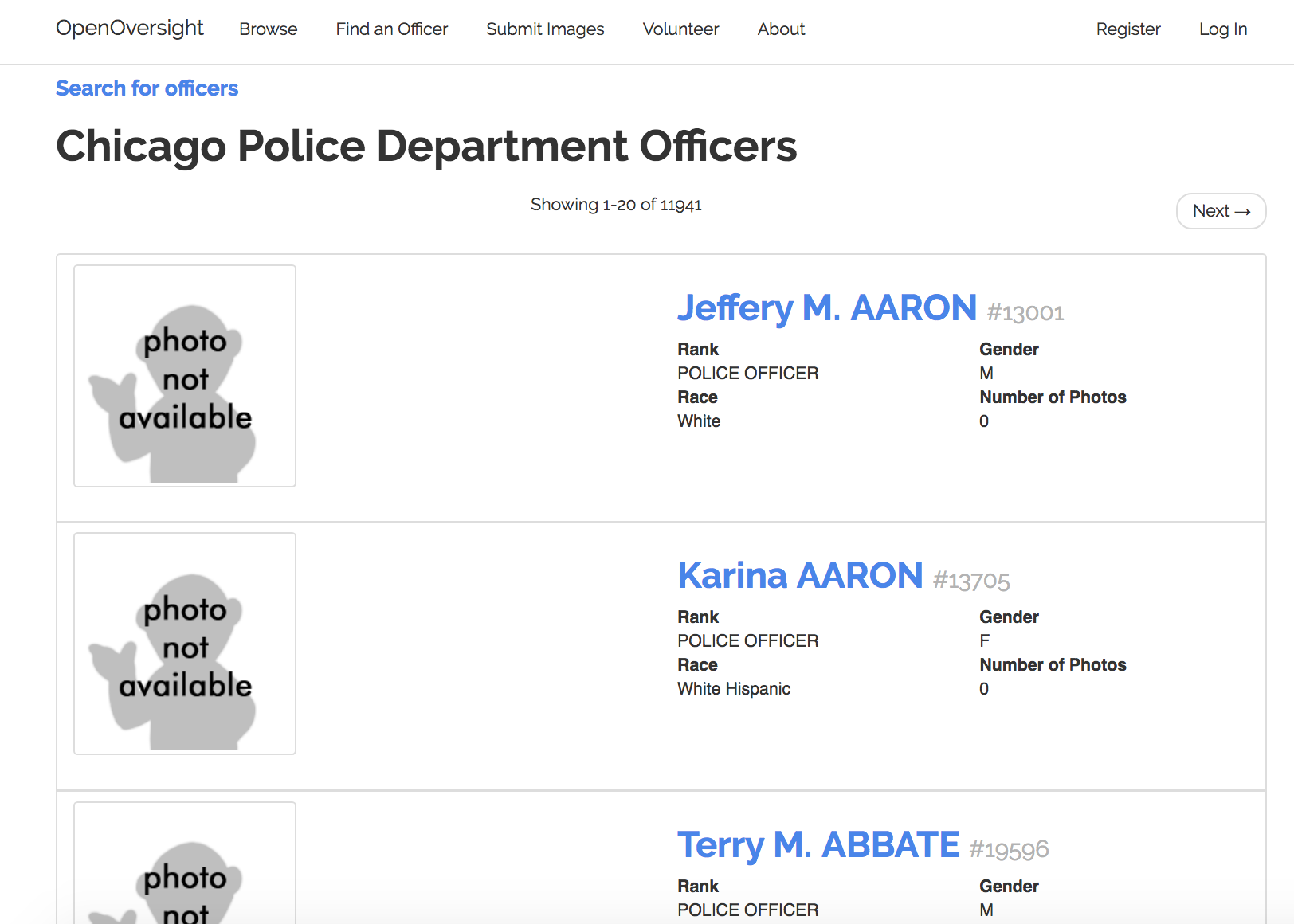

OpenOversight is deceptively simple. Anyone trying to identify a police officer can log on to the website, select the police department or federal agency, enter as much or as little of the officer’s last name and badge number as they remember, choose the officer’s rank if they know it, and enter the approximate race, gender, and age. That query searches a database of law enforcement, producing not only names, badge numbers, and identifying features, but photos and incidents too: Officer Jason D. Van Dyke of the Chicago Police Department, badge number 9465, shot and killed Laquan McDonald in October of 2014; Officer Nicole M. Rhodes of the Oakland Police Department, badge number 736, shot and killed Demouria Hogg in June of 2015; Officer Sean Aranas of the University of California Police Department, badge number 76, allegedly extorted a hot dog vendor in September of 2017.

The project isn’t perfect. Of the 684,200 patrol officers in the United States, only 12,900 have been added to OpenOversight. Some of those profiles are limited to names, badge numbers, and ranks, and just 5 percent include photos. Only five police departments—Berkeley, Chicago, New York, Oakland, and the University of California—are included, along with two federal agencies—Customs and Border Protection, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement. And, as can be seen from the examples above, only high-profile incidents are currently catalogued.

Yet OpenOversight appears to have struck a nerve. Shortly after launching in 2016, the project became the target of spammers at the encouragement of an anonymous police blog. The president of the Chicago Fraternal Order of Police has also repeatedly claimed that it endangers police officers by making them identifiable.

But accountability is exactly what Lucy Parsons Labs, the non-profit organization behind OpenOversight, hopes to achieve with this project. Pacific Standard spoke with Camille Fassett, a researcher with Lucy Parsons Labs, about OpenOversight’s reception and its future.

What was the genesis of OpenOversight?

Back in 2016, someone that Lucy Parsons Labs knew in Chicago was assaulted by a police officer. She didn’t get his name or badge number, and for big police departments like Chicago, which has over 12,000 members, this information is critical for identifying officers; in a four-year period, approximately 4,000 complaints were tossed out due to investigators being unable to identify an officer.

She said something that really stuck with us: She said that she would recognize his face if she ever saw him again. So initially OpenOversight was developed to be a digital gallery of photos of police officers. That way, if someone wanted to identify an officer, they could input whatever they remembered, like race and sex and approximate age, and get back a list of possible faces.

(Screenshot: OpenOversight)

While the vision was originally to facilitate the process of filing complaints, I think a database of law enforcement officers could be a useful tool for a variety of people. As a reporter who has covered policing, I think that being able to access an officer’s misconduct history, mentions in the news, and unit and department history is enormously beneficial for good journalism. Activists and members of the public can use this to see a list of officers patrolling their streets, and even public defenders could potentially use OpenOversight as a source of centralized information on officer misconduct.

How does OpenOversight work?

OpenOversight gets its data from two sources right now: public records and crowdsourcing. What we’re able to get with public records varies from state to state. For example, police disciplinary records aren’t public in New York, but in Illinois, it is possible to get a history of citizen complaints. We do get, at minimum, a roster of officers, including badge numbers and units. And we ask the public to submit photographs of officers in uniform—ideally those that clearly show a badge number or a name, and then have volunteers go through the images and associate each of them with an officer, therefore tying a face to a name and badge number. We’re constantly thinking about what other types of information we could include and what other sources exist to obtain it. For example, one of our newer features is that we can link, on an officer profile, to news articles about that officer.

Has Lucy Parsons Labs been directing the expansion of OpenOversight into other cities according to certain criteria?

We have been working with groups in the cities where we have had active LPL members: Chicago, the Bay Area, and New York City. Right now we want to get this working well to be useful in the cities we’re already in before expanding substantially, but we have had community groups express interest in bringing OpenOversight to new cities.

We also have groups in other cities that are using what we’ve done so far to build their own independent OpenOversight clone, which we think is great.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.