A half-degree Celsius of global warming could make all the difference for the world’s permafrost, where huge amounts of greenhouse gases have been locked in frozen soils for millennia.

Massive thawing would unleash a surge of heat-trapping CO2 and methane, potentially causing global temperatures to climb well past even the worst-case scenarios envisioned by climate scientists. That’s why capping global warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius, as prescribed in the Paris climate agreement, is so important, according to an international team of researchers who have quantified how much permafrost will melt as the planet warms.

Overall, they found that permafrost is 20 percent more sensitive to temperature increases than earlier estimates by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change had suggested.

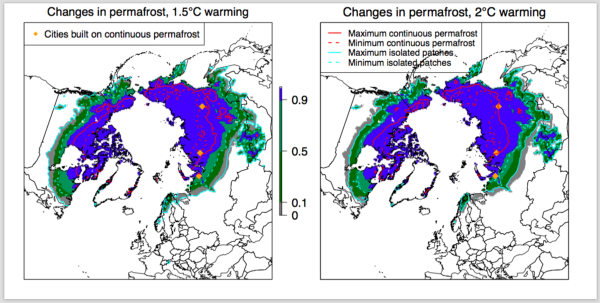

If the world warms by two degrees Celsius over pre-industrial levels, it means about 2.5 million square miles of permafrost will thaw. But capping warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius, as targeted by the international climate deal, could keep nearly one million square miles frozen, reducing the risk of a massive amount of greenhouse gases becoming unlocked from the permafrost, which in turn would fuel runaway climate change.

Melting permafrost could cause runaway global warming. It would also be very expensive, costing us $5 to $10 trillion in economic damage.

“Achieving the ambitious Paris Agreement climate targets could limit permafrost loss,” says University of Exeter scientist Sarah Chadburn, lead author of the new study published this week in the journal Nature Climate Change. “For the first time we have calculated how much could be saved. We hadn’t really calculated this in such a robust way before.”

The research team, which included scientists from the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Norway, says the findings are also important for the 35 million people who live in the permafrost zone, where widespread melting will lead to unstable ground, and will threaten towns, bridges, and roads.

The new study found a clear correlation between changes in air temperature and the growing area of thawing permafrost. If greenhouse gas emissions continue unchecked, thawed permafrost could release 1.85 trillion metric tons of carbon, dwarfing the 350 billion metric tons already released from burning fossil fuels.

By the end of this century, under a business-as-usual emissions scenario, the releases would total at least 130 to 160 billion tons of carbon, according to Ted Schuur, a permafrost researcher at Northern Arizona University who studies carbon emissions from thawing permafrost.

Permafrost is ground that stays frozen for two or more years in a row. Right now, worldwide permafrost covers an area of the Earth equivalent in size to the China, Brazil, and the United States combined, including about 24 percent of the land area in the Northern Hemisphere. Many permafrost soils are made up of dead plant matter, and, when they thaw, microbes quickly start to digest the carbon, releasing it into the air as CO2 and methane.

There’s twice as much carbon stored in permafrost than in the atmosphere, so climate scientists have long been trying to figure out exactly what it would mean for the climate if it thaws. That’s why this new study is an important step, says co-author Eleanor Burke, from the United Kingdom’s Met Office Hadley Centre, a global hub of climate research.

There’s still vigorous scientific debate about exactly how much warming permafrost will cause as it thaws, because sampling stations and studies are sparse compared to the expanse of terrain. But there’s no question that such a meltdown would be expensive, costing us $5 to $10 trillion in economic damage, according to a 2015 study. Acting now to limit greenhouse gas pollution and slow global warming will almost certainly be cheaper than taking a wait-and-see attitude, according to climate economists.

The Arctic is warming at around twice the rate as the rest of the world, with permafrost already starting to thaw across large areas. Every additional one degree Celsius of warming will thaw 1.54 million square miles of permafrost, an area larger than India.

“Simply put, the more we do to reduce human greenhouse gas emissions, the less change there will be in permafrost,” Schuur says.