Earlier this month, Aetna, the third-largest health insurer in the country, announced that it was pulling out of the Obamacare exchanges in 11 of the 15 states where it currently offers plans. The announcement came on the heels of another, this one in early August, that it was nixing the idea of expanding its Affordable Care Act exchange offerings in 2017 (into New Jersey and Indiana), and that it expected a loss of $300 million in 2016 on the ACA portion of its business.

While rumors have been swirling that Aetna’s recent announcement has more to do with the Department of Justice’s opposition to the insurance giant’s proposed merger with Humana than its bottom line, the company isn’t the first major private insurer to make such an announcement in recent months. All five of the large insurance companies in the United States are projecting losses in their ACA business for this year, and United Healthcare and Humana have also both announced plans to scale back their participation in the exchanges. By this fall, there will only be seven health insurance co-ops still standing; there were 23 in 2014.

So What Does This Mean for Consumers?

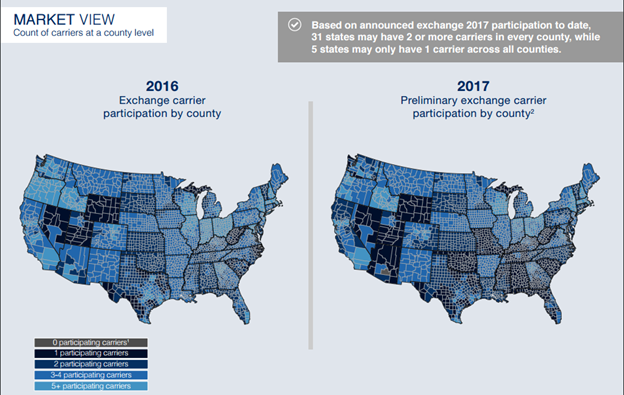

Industry experts predict that the result of all this turmoil will be fewer health insurance options for exchange shoppers, particularly in rural areas. A recent analysis of insurer participation in the marketplaces, released by health-care consulting firm Avalere, suggests that almost 36 percent of rating regions currently have only one insurer signed up to participate in 2017 (compared to only 4 percent of regions in 2016). Almost 55 percent of regions, meanwhile, will have just two participating insurers. (These numbers aren’t final — final numbers won’t be available until late September. Avalere’s analysis assumes that no new participants will enter the market, although there are some smaller insurers with limited plans who plan to do exactly that.)

A second analysis from the McKinsey Center for U.S. Health System Reform (performed for the New York Times’ Upshot blog) finds that “17 percent of Americans eligible for an Affordable Care Act plan may have only one insurer to choose next year,” in comparison to only 2 percent of Americans in 2016. The Times also reports that one county in Arizona has no participating insurers for 2017, at least not at the moment. The regions most affected are, for the most part, rural, sparsely populated, and confined to a small number of states (specifically, Arizona, North and South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida). Exchange participants in large cities, as well as most counties in coastal regions, will still have access to multiple plan options.

The map at left, from the McKinsey analysis, illustrates the geographic variation in insurer participation.

This reduction in insurers isn’t great news for consumers. All else equal, economic theory predicts that more competition in a market results in lower prices for customers, and the evidence to date suggests this holds true for health insurance exchanges. Earlier this year, the Urban Institute released a comprehensive report on health-care premiums in the individual marketplace. They found, first and foremost, that different regions were undergoing profoundly different experiences with respect to premium growth: Some regions saw premiums go up, while other saw declines. Across 499 rating areas, 29.1 percent of the population lived in areas with reductions in premiums, 19 percent lived in areas with small increases (between 0 and 5 percent), and 16.1 percent lived in areas with premium increases between 5 and 10 percent. Approximately 35 percent of the population, meanwhile, lived in ratings areas with premium increases of over 10 percent.

The Urban Institute researchers also looked at the factors associated with lower premiums and lower premium growth. “You can’t prove causation, but you can see what’s going on in areas with low premiums or low growth,” explains Linda Blumberg, one of authors of the report. “The first trend is that states with large populations tend to have lower growth and lower premiums. A bigger state is going to attract more insurers, and even some of the rating areas that have lower populations are going to benefit from that.”

Blumberg and her colleagues found that insurer participation matters, and that premiums tend to go up when insurers exit the scene. “The number of insurers matters — more insurers means lower premiums, and lower premium growth,” Blumberg says. “The other thing we’ve seen is that, when we see insurers leaving a market, you tend to see premiums going up, all else being equal.”

What Went Wrong?

So why are so many insurers losing money and pulling out of the exchanges, leaving consumers in some parts of the country with few options and likely premium increases?

The fundamental problem facing many (though not all) insurers right now is simple: Too many sick people, and not enough healthy people, have signed up for health insurance. In order to make a profit, insurers need to spend less on medical services for enrollees than they receive in premium payments from enrollees.

That means that, in any given insurance pool, they need a bunch of healthy folks to buy insurance (and not require much health care) to subsidize the health-care expenditures of the sicker people who sign up. Before the ACA, insurers selected for a healthy risk pool by denying health insurance to people with pre-existing conditions, which they’re no longer allowed to do.

By this fall, there will only be seven health insurance co-ops still standing; there were 23 in 2014.

In employer-provided health insurance plans, this risk-pooling usually happens naturally — everyone gets health insurance, sick and healthy alike. But when people are left to their own devices (and wallets) to buy health insurance, healthy individuals are less likely to sign up than their sick counterparts. Economists call this “adverse selection.” The ACA attempted to address this problem with a variety of mechanisms. The first was the “individual mandate,” which required all Americans to purchase health insurance or pay a fine. Unfortunately, more healthy people than expected have opted to pay the fine, which experts blame on the fines being too low, resulting in a risk pool that skews sicker than some insurance companies were expecting.

The ACA also included three adjustment mechanisms meant to help insurers weather the inevitable surge of sick people expected to sign up first for insurance under the ACA (many of whom had previously been denied due to pre-existing conditions). The risk adjustment program transfers funds from insurers with lots of low-risk participation to those with lots of high-risk participants; the re-insurance program provides payments to plans with a high number of high-cost participants; and the risk corridor program collects payments from plans with lower-than-expected claims and disburses them to plans with higher-than-expected claims (all three are zero-sum and do not include government subsidies). Only the risk adjustment program is permanent, the latter two will expire at the end of this year.

But these programs haven’t worked out quite as planned. The risk adjustment program has come under fire for allegedly punishing small, innovative insurers, and the risk corridor program payments have so far fallen well short of expectations. Aetna’s CEO described the risk adjustment program as inadequate in a recent interview with Bloomberg News, and a number of the co-ops have attributed their financial woes to flaws with the various risk stabilization programs.

Can We Fix It?

ACA supporters contend that the current instability in the market is temporary. Insurers, they argue, are simply learning to serve a different pool of consumers, under a different set of regulations.

There’s some evidence to support this argument. Not all insurers are giving up on the exchanges. In early June (before Aetna’s announcement), researchers at the Commonwealth Fund, a non-partisan health-care research shop, reported on the second-quarter earnings calls of insurers. Their conclusions were optimistic. “The truth is that not all insurers will thrive in this new and still developing marketplace, where consumer protective rules reward effective risk management and prohibit the discriminatory underwriting practices that insurers could rely on in the past,” the researchers wrote. “Nevertheless, there are clearly insurers that see business value in marketplace participation and are committed to the underlying principles of the ACA.”

In particular, several insurers that had previously offered Medicaid plans (and, thus, had existing rates negotiated with narrow networks of providers) — Centene and Molina, most notably — are thriving in the ACA exchanges, which suggests that “fixing” the ACA exchanges may entail accepting that the plans on offer look different than expected.

“These are insurers that had previously negotiated with providers to have a network, and they tended to have negotiated provider payments that were low compared to the provider sector, so that they could win these [Medicaid] contracts with the state,” Blumberg explains. “But an insurer of a different type that may have dominated the private market and didn’t have to complete on price … now they do.”

The fundamental problem facing many insurers right now is simple: Too many sick people, and not enough healthy people, have signed up for health insurance.

There are also changes to the law that could be made, although some are controversial. The government is working on tweaks to the risk adjustment mechanism. And most health-care experts at this point believe that more can, and must, be done to encourage healthy people to participate in the health-care exchanges in order to create an overall healthier pool. Both the subsidies for purchasing coverage and the fines associated with the individual mandate could be increased. In a recent interview with Vox, the health economist Uwe Reinhardt pointed out that Switzerland, which relies on private insurers, takes a much sterner approach to people who opt out.

“When they run these exchanges, they accompany them with a very harsh mandate,” Reinhardt said. “If you don’t obey the mandate, the Swiss find out, and they go after you and garnish your wages. If you’re not insured, they’ll look at your wages and recoup the premiums you owe. They’re very tough. And we’ve never been tough.”

Emily Curran, a co-author of the Commonwealth Fund report, also points out that some states have done a better job than others of encouraging insurer participation. “It’s important to consider what flexibility the state-based marketplaces have in order to make sure this is a sustainable, competitive marketplace,” she says. “They can set plan participation requirements and they can make decisions regarding structure.”

Curran cites California and Maryland as two states that have worked hard to encourage a robust marketplace. California encouraged insurer participation upfront by limiting future opportunities, although they’ve since allowed new entrants in ratings areas with limited competition. Maryland, meanwhile, forbids insurers from offering individual products outside the marketplace unless they also participate in the ACA marketplace. Maryland also operates the country’s only all-payer rate-setting system, which dramatically reduces barriers to entry for smaller insurance companies.

And then, of course, there’s the public option, which President Barack Obama recently reiterated his support for in an article for the Journal of the American Medical Association. Such an option, Blumberg suggests, would not only provide at least one guaranteed option in rural areas but might also help contain premium growth in other markets, since the presence of a low-cost public plan would force private insurers to compete more aggressively on price. A similar effect is already occurring in markets with low-cost insurers. The Urban Institute’s analysis found that markets with a Medicaid insurer had lower premiums than markets without such an insurer (though the analysis doesn’t establish causation). Specifically, markets with a participating Medicaid insurer experienced a relative premium change 7.3 percentage points lower than comparable markets without such an insurer.

“You could do this universally, you could do it across the board,” she says. “Or you could do it in the areas where the markets are the weakest. And you could do it in a number of ways, but you need a plan that is going to be able to catalyze some competition for the remaining insurer or insurers to respond to.”

Of course, not all of these solutions are politically feasible, and a lot depends on the outcome of the upcoming election. But there are effective changes that can be made, and claims that Obamacare is failing are greatly exaggerated. The ACA’s individual health exchanges are clearly facing some challenges, but it’s not time to throw in the towel yet.