If you’ve ever visited the Capitol in Washington, D.C., one of the things you probably noticed is the huge number of congressional staffers. They’re everywhere, running to policy meetings, sitting in on committee hearings, helping you out at a front desk, giving tours, and maybe even offering to sit down to chat with you because your member of Congress is busy that day.

Staffers aren’t simply 22-year-olds who get coffee, make copies, and print out emails for their technologically challenged bosses. They provide research and expertise.

It’s a very different experience in most state legislatures, where you’re more likely to run into an actual elected official than one of her staffers. There’s just not a lot of staff in our state legislatures. As I recently learned from a talk by Karl Kurtz of the National Conference of State Legislatures, there are a total of about 34,000 state legislative staffers—including permanent staff, temporary aides for legislative sessions, and others—in all 50 state houses combined. Meanwhile, there are, as of 2009, nearly 23,000 staffers just in Congress. Congress is, in fact, the best staffed national legislature in the world.

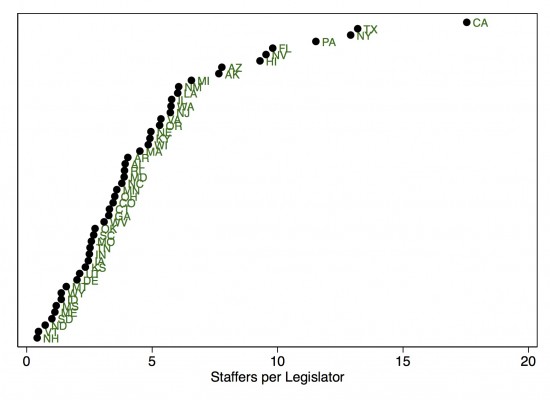

If you break the numbers down by state, it’s clear that those 34,000 staffers are not distributed evenly. A few large states with professionalized (year-round, well-paid) legislatures have most of them. California, unsurprisingly, is in the lead, with 2,106 staffers for its 120 legislators—roughly 18 staffers per legislator. Most other states are much smaller, with a median of 3.8 staffers per legislator. New Hampshire has only 179 staffers for its 424 legislators, less than half a staffer per member.

This relative lack of staffing is not a small matter. Staffers aren’t simply 22-year-olds who get coffee, make copies, and print out emails for their technologically challenged bosses. They provide research and expertise. A legislator who is writing a bill or considering a roll call vote requires information: How will this bill affect her district and state? Which key interest groups support it or oppose it, and why? Is public opinion running for it or against it? Will it actually help or hurt the state in the years to come?

The main way to get answers to these questions is to rely upon legislative staff. At least, that’s what members of Congress get to do. If state legislators don’t have such a resource, they’ll have to rely on someone else: the governor (making the legislators even more subservient to the biggest political office in the state), lobbyists (who certainly have their own agendas), party leaders, or even their own best guesses.

Having a decent number of staffers available gives state legislators a better ability to make competent, independent decisions and to resist the influence of other actors. They better enable the legislature to do the governing job we’ve assigned to it. It’s a pity that such expenditures are often described as wasteful.