Following national trends, last week’s election was a solid win for Democrats, who swung over 300 state legislative seats across the country, bringing some six legislative chambers to their side. This wasn’t a historically extraordinary shift, but it was consistent with expert expectations and also with the similar gains Democrats made in the House of Representatives.

These shifts will, of course, have important consequences for residents of those states. Many state legislative laws, covering topics like education, transportation, and health care, will have a far greater impact on residents’ lives than those being considered by Congress.

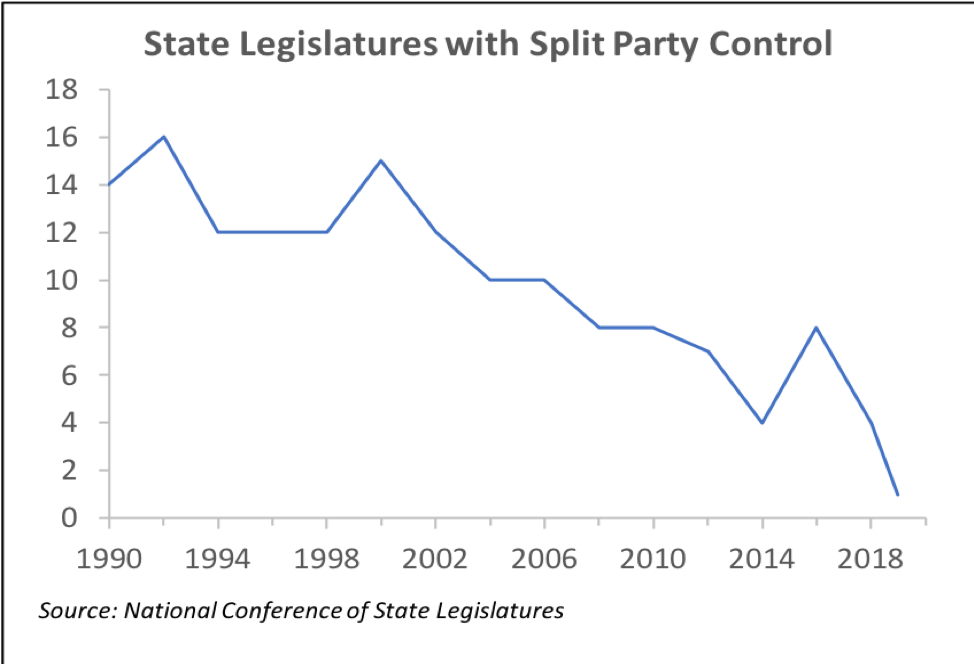

Perhaps even more important, though, was the shift in unified party control. Congress will have split party control next year, and this is far from unusual at the national level—Democrats held the Senate while Republicans held the House as recently as 2015. And quite a few state legislatures have often seen split party control.

Starting in January, only one state legislature—Minnesota’s—will be under split party control. In that state, Democrats took over the state house but fell one seat short of flipping the state senate last week. The last time just one state legislature was under split party control was 1914.

This represents an important shift in Americans’ voting behavior. Split-ticket voting has been on the decline for decades, which helps explain why events like Republican governors winning in Democratic-leaning states like Massachusetts or Democratic senators winning Republican-leaning states like West Virginia are increasingly rare. Over time, states are increasingly being represented by elected officials whose partisanship accords with the states’ voters.

What does this mean for those states? There were only four states that had split party control prior to the election—Colorado, Connecticut, Maine, and New York. All four of those shifted to unified Democratic control. Importantly, all four will have Democratic governors next year as well.

Colorado has had some recent successes in bipartisan governance despite a highly polarized legislature, in part because pragmatic and relatively experienced legislative chamber leaders worked together with a centrist governor and set out a clear road map of which issues they felt they could work together on. This year, that state’s governor, state house speaker, and state senate president were all termed out. Colorado begins 2019 with new chamber leaders and a new governor, Jared Polis. Polis certainly wasn’t the left-wing extremist his Republican opponent portrayed him to be during the recent campaign—Polis isn’t even the most liberal Democratic member of Congress from Colorado. Nonetheless, he ran on a fairly liberal agenda of increasing early childhood education, expanding access to health care, and powering the electrical grid with 100 percent renewable sources in the next two decades. And he doesn’t particularly need to confer with Republicans to translate this agenda into law.

New York is also set to move in a more liberal direction, with the Democratic flip of the state senate and the demise of the Independent Democratic Conference—a coalition of moderate Democratic senators who worked closely with Republicans—in the September primaries.

Of course, a dozen states with unified legislative party control still have a governor of the other party, so legislative parties don’t have carte blanche in deciding how to govern.

Nonetheless, the 2018 election results mean that the states are going to continue to march away from each other in terms of policy, and that people’s decisions about where to live will have increasingly important consequences for how they live. It affects one’s taxes, access to health care, the availability of reproductive services or firearms, quality of schools or roads, how easy it is to vote, and a whole host of other things of vital importance to people’s lives. And, increasingly, one party gets to make these calls in each state, and it doesn’t need to check in with the other party to do so.