James Carey was a junior officer on a ship in the South Pacific during the Vietnam War when he was appointed one of the least envious military roles at sea: voting assistance officer. The job — a part-time one, of course — came with a massive three-ring binder of the byzantine rules and regulations for voting absentee in the 50 states, six territories, and thousands of counties back home.

“This was before e-mail,” Carey said, lest we forget that such a time ever existed. “That would mean if you’re on a ship, and you’re trying to register to vote, or to get more information on voting, you have to write a letter that goes to the ship post officer, that goes in a mailbag, which goes on a helicopter. The helo takes it to a carrier, and the carrier takes it ashore to Subic Bay in the Philippines.”

From there, it heads back to the United States and enters the U.S. Postal System, on the other end of which some local election official finally receives it weeks later.

“And maybe they need more information from you!” Carey said. Then he describes the deflating reverse process that second letter must take back across the globe. “If this is anywhere near close to an election,” Carey said, “you can imagine you’re not going to get to vote.”

Miller-McCune’s Washington correspondent Emily Badger follows the ideas informing, explaining and influencing government, from the local think tank circuit to academic research that shapes D.C. policy from afar.

In retrospect, this sounds like one of those quirky historical anecdotes about the dislocated life of soldiers at war. But the process Carey describes did not change significantly over the following 40 years (although most of the ships moved out of the South Pacific and the base at Subic reverted to the Filipinos). America has sent repeated generations of soldiers to war — including those who’ve gone to Iraq and Afghanistan – with little chance of voting on the politicians who sent them. (During the Civil War, when absentee voting was first allowed, some troops were allowed to return home to make sure their votes — generally pro-Lincoln — were counted.) This year marks the first presidential election when all of this will start to change.

“Everyone understands that it’s important that those serving us overseas have an opportunity to express their voice in our democracy,” said David Becker, who directs the election initiatives at the Pew Center on the States. “But I think many were unaware of the significant obstacles those citizens face. While they’re protecting all of our rights, their most fundamental right is at risk.”

Harry Truman first barked at Congress about this problem 60 years ago during an era, spanning World War II and the Korean War, when more Americans were stationed overseas — and disenfranchised there — than at any point in history. But by 2008, states were still mailing election materials the old-fashioned way, and sometimes even requiring voters to notarize them before sending them back. In 2008, it still took about 18 days for a piece of mail to go from Afghanistan to a stateside election official.

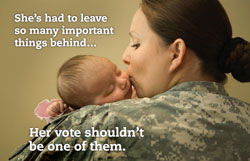

An example of a promotional campaign designed by The Pew Center on the States.

In 2009, Pew published a startling report that found that 25 states and the District of Columbia did not allow enough time for overseas service members to vote. The Election Assistance Commission estimated in 2007 that about 1 million ballots were distributed to overseas American voters (a group in total that’s estimated to include about 6 million people). Only a third of those votes were actually cast or counted. In another survey of military personnel who said they did not vote in the 2004 presidential election, 30 percent said their ballots never arrived or came too late. Another 28 percent were befuddled by the whole process.

Pew’s report — and a powerful accompanying ad campaign — helped spur Congress to finally pass legislation repairing the 1986 Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act. That earlier bill reiterated the voting rights of overseas service members but didn’t do much to protect them. The 2009 law, on the other hand, required states to plan for a 45-day window for ballot “round trips” and to provide voter registration and absentee ballot applications electronically. It also eliminated those notary requirements.

An example of a promotional campaign designed by The Pew Center on the States.

“I’m sure some of these county clerks get a ballot back, and it has mud on it, or sand on it, or bugs, and I’m sure they wonder, ‘What’s going on?’” said Carey, who is now a retired rear admiral and a senior adviser to the Pew project. “But you’re not going to the local grade school to cast your ballot. And how many notaries do you think are in foxholes with you? Obviously, nobody was thinking about all of these circumstances.”

Since the passage of the 2009 federal law, Pew’s campaign has shifted to the state level. It has just released another report surveying the 47 states and the District of Columbia that in 2010 and 2011 alone passed new laws aimed at overseas and military voters. (Alaska, Pennsylvania and New Mexico did not pass applicable laws in those years.) After decades of delay – some of it caused by the pace of technology, some by sheer inattention – nearly every corner of the country has now addressed the problem in a little over two years, in time for the 2012 presidential election.

All 47 of these states will now electronically transmit blank ballots, among other reforms. We have yet to see the day, though, when military personnel (or anyone, for that matter) can send a completed ballot back electronically as well. In this sense, technology is solving many of the problems of overseas voting, but there is a limit to how far many people are comfortable applying it. Carey, though, thinks of the sailor on a long submarine deployment who still won’t be helped by all of these reforms.

“We in the military send highly encrypted, highly secure classified messages all over the world,” he said. “Banks send not just billions but trillions of dollars all around the world electronically. I have a hard time believing that the system is all that jeopardized if we were, just because of the difficulty of their situation, to allow the military to transmit them back electronically.”

For now, though — and early primary results confirm this — many people will be able to vote in 2012 who couldn’t four years ago. It’s unclear if this will in some way impact the country’s political landscape, although military voters historically skewed Republican. Precise numbers of overseas voters are hard to come by. But Becker and Carey argue that deployed service members aren’t the only ones touched by the new legislation. These protections say something about American democracy on the whole.

“Who sends these people there?” Carey asked. “They’re not going overseas to get shot at of their own accord. Our government sends them. And who is our government? Well it’s the people we elect. It seems to me, if we’re going to be sending American citizens into harm’s way to lose a leg, to lose an arm, to lose a life, they are surely first among equals in who we need to make sure gets an opportunity to vote – and to make sure that that vote gets counted.”

Sign up for the free Miller-McCune.com e-newsletter.

“Like” Miller-McCune on Facebook.

Follow Miller-McCune on Twitter.

Add Miller-McCune.com news to your site.