A new study of how pro-ISIS groups form and die on a Russian Facebook clone shows that the rate of pro-ISIS group creation accelerates before a big event.

By David Shultz

(Photo: Michael Smith/Newsmakers)

One of the strangest things about the rise of ISIS has to be its online recruitment tactics. People around the world, with no actual ties to real live members of the Islamic State, are being seduced by — or at the very least exposed to — the radical idealism via the Internet. And like many things on today’s Internet, much of this recruitment is taking place on social media.

Scientists have wondered if ISIS’s social media habits might reveal insights into the organization itself; or, better yet, if those habits might present a strategy for stopping it. In a newstudy published in Science, researchers suggest that data gleaned from a Russian version of Facebook, called VKontakte, can predict when ISIS activity will spill over into the real world. The scientists found that the number of pro-ISIS groups on VKontakte increased rapidly just before a real-world terror attack The trend has little to do with the individuals, but instead speaks to the ecology and functionality of the larger ISIS Internet community.

For more, Pacific Standard spoke with Neil Johnson a physicist at the University of Miami and lead author on the paper, about the results.

As I understand it, a lot of this research was born out of previous work you did on using the Internet to monitor protests and other radical behavior. What was the question you wanted to answer at the beginning of all this?

The particular question was: “If you know, as we all do, in principle, all of the information that’s online, what could that tell you about events in the real world?”

The idea is that, if people are thinking about it, they must be Googling it. So we looked at the volumes of search terms, the number of tweets containing the word “protest.” But the bottom line is that there’s so much noise that it’s not useful for talking about what’s in the real world. I can tweet something about the Stanley Cup, but I don’t have any influence on it just by tweeting about it. So, unfortunately, after two years the answer was no, it doesn’t tell you much.

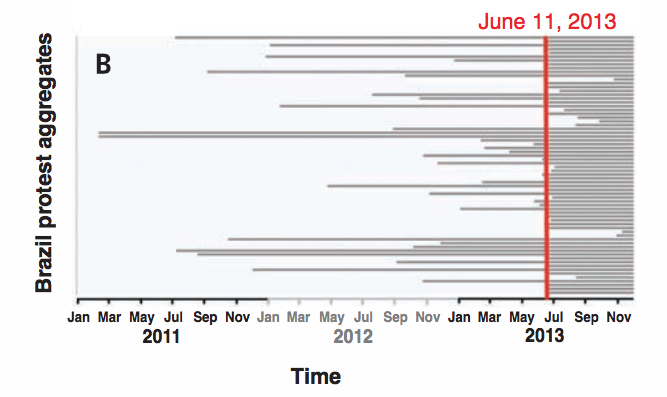

But there was one particularly famous case — the Brazil protest that arose in 2013. We missed it. We missed that prediction using our search of keywords and chatter, and so did everybody else. One immediate conclusion from that was that it’s just not possible — there’s nothing going on online that then relates into the real world. But we couldn’t quite believe that, so we went back and had a look at the Brazil protest and we decided to discard looking at keywords and chatter.

And this is when you shifted to looking at Facebook groups? What made Facebook so useful?

There’s one thing you can do on Facebook and every copy of Facebook around the world: create communities. You can create standalone entities that people then become members of and that virtual space — which we call an aggregate — enables people in them to share things.

When we dug into Facebook — when we looked closely in relation to Brazil — we saw that the rate of creation of these aggregates escalates, before the protest — and not just two days before the protests, but months or even more than a year. So we thought maybe we’d seen something. Maybe the way that humans were aggregating around would be similar for other types of “extreme activities.”

A graph showing the number of Facebook groups dedicated to protesting in Brazil leading up to the outbreak of the “Brazil Winter,” which began on June 11, 2013 (red line). The rate at which groups form, according to new research, can be used to predict when online actions will spill over into the real world. (Chart: Science)

But you couldn’t use Facebook to study ISIS. How come?

Facebook shuts them down almost instantaneously, so quick we could hardly even capture them.

So without Facebook, how is ISIS organizing?

VKontakte is exactly like Facebook — it even looks like Facebook — but the fortuitous thing for our research was that they didn’t shut down pro-ISIS groups quickly enough. They do eventually shut them down, but not so quickly that we couldn’t capture what was happening.

What did you learn on VKontakte?

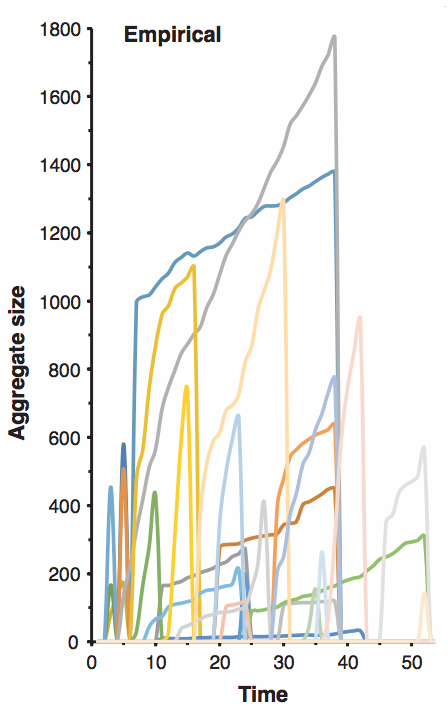

By tracking them over time we’ve shown that the aggregates grow and die in a vaguely shark-fin shape. The membership grows in some slightly irregular way, with new members coming in, or other by smaller aggregates coalescing. And then there’s these occasional vertical lines where they just end — where they shut down.

A graph showing the “shark fin” growth and shutdown of various pro-ISIS groups on VKontakte. (Graph: Science)

When things shut down, it’s closing that virtual space where they live — that aggregate community. The people scatter and they go to other places. They join other aggregates, and those aggregates grow and then they shut down, and others grow, etc. All of this is going on and it struck as like an ecology.

And the mathematics you’ve used to describe the growth and movement of these VKontakte groups is the same sort that we’ve been using in biological ecology for years?

Absolutely. Like with all things in science, you never really invent anything, you just kind of adapt it. People have applied these equations to groups of chimpanzees, birds, fish.

Are there any notable differences?

In nature, there’s never the equivalent of the shut down. Animal groups can divide in two or three or five, and they may merge again or not, but you never get them scattering in all directions. We had to put that extra bit into the mathematics, but when we did — at least visually — we knew we were on the right track because you get start to see shark fin shapes appearing in the model data. At the head of these real-world onsets, the creation of these shark fins escalates.

So, according to your research, if we see a sharp uptick in pro-ISIS group creation, we might know that a real-world terror attack is more likely?

I’m always a bit wary of the prediction thing. It almost turns the problem of dealing with extremism online into an engineering problem. We’d never get into a plane if the understanding of planes was purely anecdotal. We always hope that there’s some underlying science and systems-level understanding of the whole thing. And I would like to think that that’s what this turns it into.

Now if we know it looks like it’s spiking up, we can start to look at how we want to intervene. We either monitor it and think of it as a prediction, or we intervene and break up these escalations.

Does the data show any promising ways to disrupt ISIS organization?

If we want to stop the bigger aggregates from forming, you can break up the smaller ones. If the bigger ones are somehow harder to destroy — and let’s face it, it’s an online system, so these aggregates can be quite clever with how they shield themselves — you can shut down the small ones because they will grow into the larger ones.

But if everyone just scatters to new groups, how do we stay ahead of that?

As soon as you shut one down they scatter and join others. It’s a little bit like the case of cells with viruses. The virus wants the cell to burst — it’s good for it because then it spreads. There’s a certain rate of shutting down that you need to do to stop that outbreak. That was based on a piece of work I’ve done earlier on contagion. It follows exactly the same math.

The math shows there’s a very precise rate at which aggregates need to get shut down. If you don’t want the pro-ISIS or pro-extreme aggregates to grow into one huge global aggregate, then you’ve got to shut it down faster than this precise formula that we’ve come up with. To be able to put that down rather than guess at it with words, as a physicist, I find that quite attractive.

What about the “lone wolf” who isn’t necessarily acting in coordination with large groups? Like in Orlando, perhaps.

Our works suggests that the lone wolf is only truly alone for a small time. They’ve either been in an aggregate or they’ll soon be in an aggregate. That’s how they get their information. But I don’t think it could’ve predicted the Orlando attacks. When it’s one person, then with the information that we have now we wouldn’t have been able to predict that. If we had, say, a no fly list or something like that, we could try to match it up with the people in the aggregates. But at the present time, and I’m not saying it’s not possible, we’re not able to map individual users of the aggregates [as potential terrorists.]

Our work is a shift away from thinking that there’s one object or person, one bad guy responsible for these acts. It leads to a collective view of how really serious pro-ISIS support, and support for any kind of extremism exists online. That’s the scientific shift — from the individual to these aggregates.

||

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.