The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau announced new protections for users of prepaid debit cards. Will they do enough?

By Dwyer Gunn

(Photo: Christopher Furlong/Getty Images)

Last year, a technical glitch meant that thousands of clients of RushCard, the prepaid debit card company founded by the hip-hop mogul Russell Simmons, were locked out of their accounts for days on end. The brief crash called attention to the rapidly growing alternative financial services sector—and to the unregulated nature of the prepaid debit card market.

Now, that market is about to get slightly more regulated. Yesterday, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau announceda series of new regulations aimed at improving customer protections. The rules, which have been under consideration for four years, will apply to reloadable debit cards (like RushCard), as well as payroll cards, government benefit cards, tax refund cards, mobile wallets, and other electronic accounts. By and large, the new CFPB regulations are focused on transparency and on providing consumers with the same protections afforded to users of checking accounts. Along with offering greater protections for users whose cards are lost or stolen (and requiring timely investigation and resolution of account disputes or complaints), the regulations mandate a clearer disclosure of any fees associated with the cards.

The new CFPB regulations also seek to regulate those prepaid cards that provide overdraft credit lines to consumers, a feature that some argue can lead to excessive fees. Under the new regulations, providers must assess a person’s credit worthiness before extending a credit line (just as standard credit card companies are required to do), and must stick to reasonable fee and repayment schedules.

The prepaid debit card market has exploded in recent years — almost $65 billion was loaded onto “general-purpose re-loadable” cards in 2012.

The prepaid debit card market has exploded in recent years — almost $65 billion was loaded onto “general-purpose re-loadable” cards in 2012, up from less than $1 billion in 2003, according to the Mercator Advisory Group — and the growth is expected to increase. The cards, which don’t require a credit check, have historically been popular among low-income Americans that don’t have a bank account, although a 2015 study from the Pew Charitable Trusts found that much of the growth between 2012 and 2014 came from consumers who do have a bank account.

For the most part, prepaid debit card users are drawn to the cards because they’re fed up with the traditional banking system, which has not been very friendly to low-income consumers in recent years. Most basic checking accounts now carry monthly fees and minimum balances, and some report being confused by the unpredictability of overdraft fees.

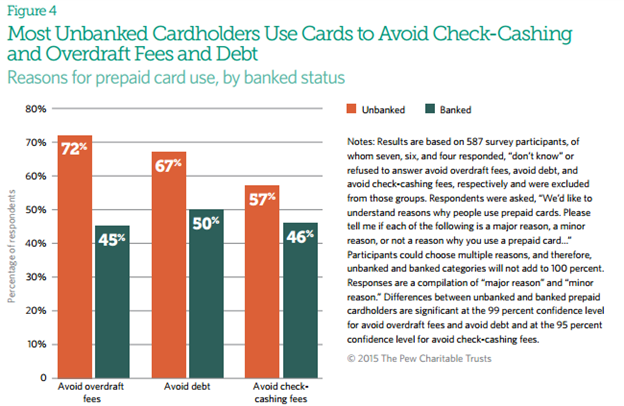

(Chart: Pew Charitable Trusts)

The chart to the left, from the Pew report, illustrates why consumers use prepaid cards.

John Caskey, an economics professor at Swarthmore College, elaborated on this concept for a piece I wrote last year. “You hear people complain about ‘high fees’ and ‘uncertain fees’ at banks,” Caskey said. “High-income people often leave a buffer in their accounts, but for a lot of low-income people, they’re going to draw down their accounts to near zero at the end of the month or pay period, and they don’t know if they’ll overdraw. So they’ll periodically get fees that they can’t predict.”

Barring a sea change in the traditional banking industry, prepaid debit cards probably aren’t going anywhere. The CFPB’s new regulations won’t do much to address what is perhaps the biggest driver of growth in the prepaid market — the lack of traditional checking accounts that are affordable for low-income people — but they will provide crucial protections for the financially vulnerable users of the cards.