Cody Wilson was 24 when he decided to design a gun that anyone could make at home with a basic 3-D printer. It was 2012, and he was slogging through law school at the University of Texas–Austin, reading anarchist and anti-state philosophy in his spare time, hungering for a sense of purpose. Almost as soon as he announced his plan for a “wiki weapon” online, it prompted a wave of media attention. In 2013, he uploaded blueprints for a print-at-home rifle receiver that you can combine with factory-made parts to create an unregistered semi-automatic AR-15. More famously, he also uploaded blueprints for the Liberator, a plastic pistol you can print entirely in the privacy of your own garage.

The Liberator isn’t much of a gun. Among other problems, it cracks easily and becomes unusable, often after a single shot. Any American looking to shoot someone would have a much easier time buying a standard gun at the nearest gun show. The Liberator’s power lies less in what it can do and more in the world it suggests: a world of Liberator-style guns and file-sharing networks that spring up as quickly as they get shut down. Shortly after Wilson posted the file to his website, Defense Distributed, the Department of State ordered him to remove it. But Wilson’s team claimed that 100,000 people had already downloaded it, and today the file is easily accessible.

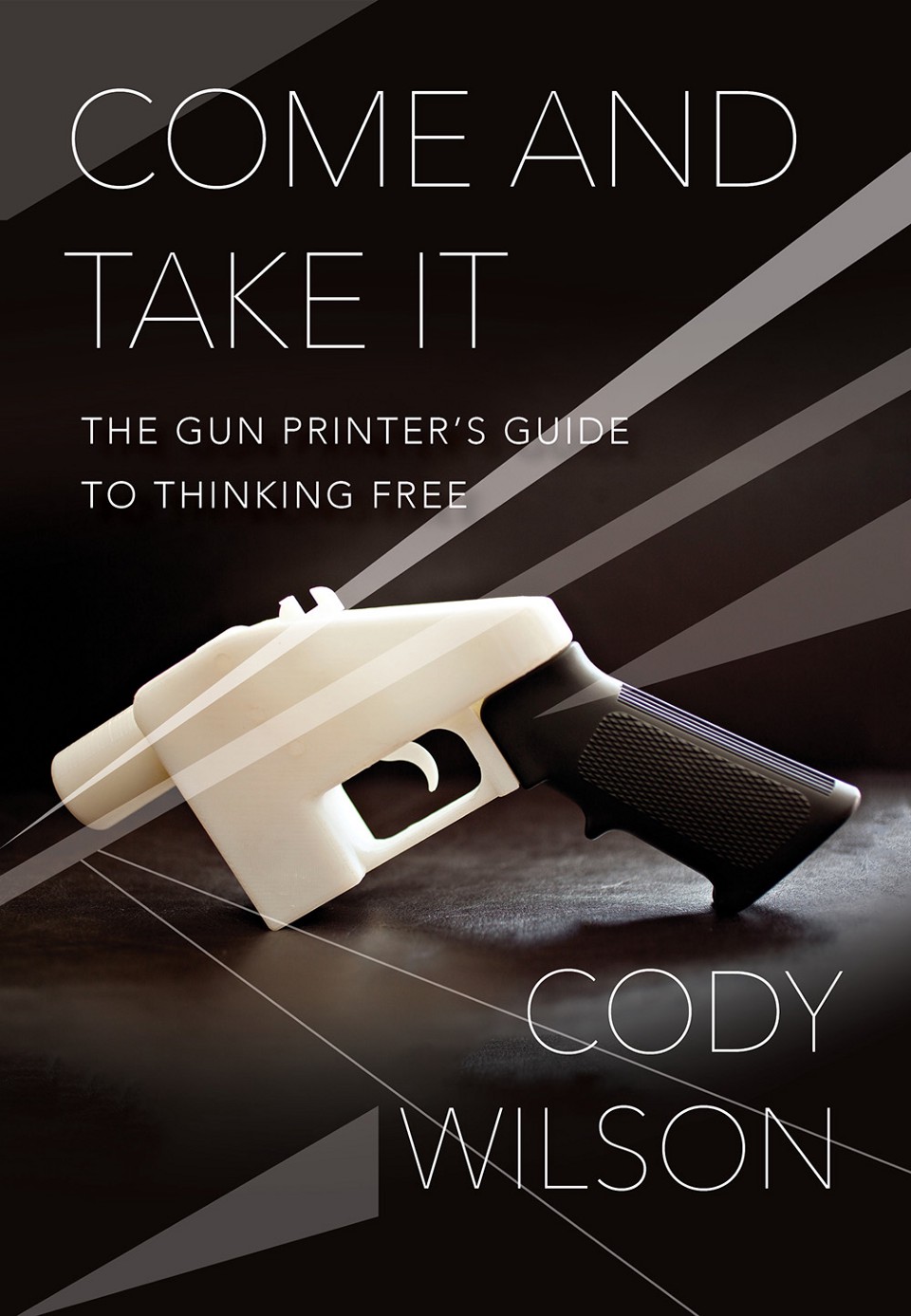

For his efforts, Wilson has been profiled breathlessly by journalists around the world; invited to speak at the Museum of Modern Art; and named both a “Most Dangerous Man on the Internet” and “Most Dangerous Man in the World” by Wired. The guy makes good copy, in part because his project is a plausible intersection for all manner of overlapping, hot-topic trends. Defense Distributed is a gun control story; a free speech story; a WikiLeaks-inflected “Internet dissemination versus The Man” story; and a disruption story. Plus, Wilson is colorful: young, brash, and prone to peppering his speech — and now, in his memoir, Come and Take It: The Gun Printer’s Guide to Thinking Free, his prose — with allusions to philosophers as disparate as Nietzsche, Foucault, Proudhon, and Baudrillard.

The short version of Wilson’s philosophy in Come and Take It: State power is out of control, and we’ve forgotten how to be individuals. This problem, as Wilson sees it, is so totalizing that any belief in piecemeal reforms is delusional. Only a complete rupture with the present will do. Finally: This necessary rupture will be achieved only by Liberator-type projects that break the state’s monopoly on force. Only then will we be transported from the stale present into the clarifying light of true freedom.

For all of the attention lavished on Wilson’s projects, very few of his interviewers have asked him to elaborate on what the post-rupture world might look like. At first glance, Come and Take It strikes a similarly vague note. For Wilson, the connection between his project and a better (truer, freer, less coercive) future is self-evident. Instead of trying to prove the case, he instead charts the play-by-play of his transformation from frustrated law student to enfant terrible of the radical gun-deregulation movement. The basic structure and tone will be familiar to anyone who has seen Fight Club or The Matrix: alienated young man, armed with extra-special sensitivity to the petty delusions of his fellow humans, finds his way into an underground network of similarly minded men.

In prose that oozes alienation, Wilson recalls traveling to California, Switzerland, Austria, and England, making contact with gun enthusiasts, anarchists, hackers, cryptocurrency activists, and the like, all claiming they know how to usher in the revolution, or at least how to prepare for it (or, at the very least, how to get Cody Wilson some money).

(Photo: Gallery Books)

Along the way, he drops a few hints of a worldview just slightly more specific, and significantly more disturbing, than unregulated guns mean freedom, freedom is good. These hints comprise a very small portion of the book (consolidated, they would take up little more than a single page), but they are its most telling element — the expression of a racial panic, an aspect of Wilson’s ideology curiously absent from coverage of his project to date.

The first clue passes so quickly it’s easy to miss. In an airport en route to London, Wilson finds himself overcome by disgust at a security agent, whom he describes as a “slope-backed cretin.” Later, Wilson goes out of his way to recall how, in Austria, he found Slovaks to be a “hideous race,” claiming that “you see it in how they walk, how they carry themselves.” Observing a group of students watching President Barack Obama on television, he quotes every eugenicist’s favorite snippet of Nietzsche: “Too many are born.” Sitting on a bench in Vienna, he whistles “Dixie,” the de facto anthem of the Confederate States of America. (Wilson, who is white, was born and raised in Arkansas.) In California, he talks strategy with “Mencius Moldbug,” the Internet pseudonym of Curtis Yarvin, a programmer and central voice of the “neo-reactionary” right, who has proclaimed (though Wilson doesn’t mention this) that some humans are better suited to slavery than others.

On the surface, Wilson’s stated concern is freedom. But scratch that surface and it becomes clear that, while Wilson’s “freedom” might mean, in part, “freedom from the state,” it also means freedom, backed by force, from the “too many”: the conformist sheeple, hideous races, and slope-backed cretins of the world.

If this sounds like a stretch, I recommend you pull up Wilson’s Twitter feed and scroll back to May 9th, where he affixed the following caption to a photograph of a racially diverse group of Hillary Clinton supporters: “Quick, find one genetically fit person.”

Wilson’s project might, as a variety of media observers have speculated, pose deep dilemmas about how to regulate open-source software in an increasingly networked, print-on-demand future. His memoir, though, suggests the existence of much more pressing questions among his sizable audience (Simon & Schuster reportedly paid $250,000 for his book). As media scholar Robbie Fordyce has noted, users of the white supremacist website Stormfront frequently discuss the importance of 3-D printing — and not just of weapons — in the coming of a white utopia.

Come and Take It is an especially illuminating read in the Season of Donald Trump — another white preacher who stumbled onto a bigger audience than almost anyone foresaw, and whose nativist appeal the overwhelming majority of politicians, journalists, and pundits were much too slow to understand. Trump promises white America that a “great again” future awaits, and that he knows exactly how to get there. Wilson sings a similar song, but adds a verse: To prepare for greatness, grab (or print) a gun.