Later today, the Justice Department is expected to release a report with the results of an investigation that was launched last year after Darren Wilson, a white police office, fatally shot Michael Brown, a black teenager, in Ferguson, Missouri. A preliminary summary of the report details the bias and racism present in Ferguson’s police force, as well as their consistent use of excessive force.

Federal investigators used hundreds of interviews, 35,000 pages of police records, and racial data on police stops to compile the report. The New York Times wrote:

“[Over] the past two years, African-Americans—who make up about two-thirds of the city’s population—accounted for 85 percent of traffic stops, 90 percent of citations, 93 percent of arrests and 88 percent of cases in which the police used force. Black motorists were twice as likely as whites to be searched but were less likely to be found in possession of contraband such as drugs or guns.”

While Ferguson officials are now facing the very real possibility of being sued by the Justice Department on charges of violating the Constitution (unless it negotiates a settlement), we shouldn’t forget that a number of other police stations have faced similar investigations. From Seattle and Portland to New Orleans and Miami—and even smaller units like East Haven and Maricopa County in Arizona—there are many cases against departments that have been “under federal investigation for excessive or lethal use of force against and discriminatory policing of people of color, other minorities, and vulnerable populations.”

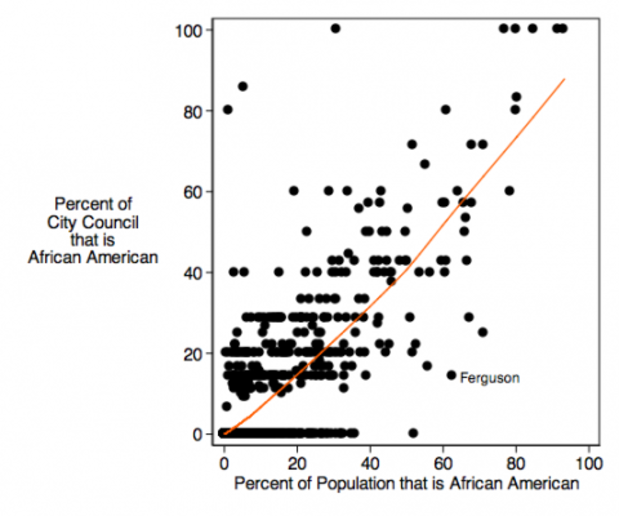

This institutional bias in Ferguson is perhaps most starkly manifested in their city council: In 2001, for example, the city, the majority of which is black, had zero African Americans on their city council. That number has since grown, but as indicated by the chart below, which uses data from 2011, it still remains a major outlier in terms of black representation.

The issue, though, ultimately lies with the police force, which also has a striking disparity in African American representation. While the community of Ferguson is two-thirds black, the police department is 94 percent white. It seems like a logical solution would be to increase the diversity of Ferguson’s police department, as Attorney General Eric Holder and Ferguson Police Chief Jackson have both advised, but it’s not that simple. As we reported last summer:

Research by criminologists in the past has similarly rejected simplistic solutions to police violence and racial tension. In an analysis of 186 “officer-involved shootings” in Riverside County, California, researchers writing for the journal Criminal Justice and Behavior found that white officers were more likely to shoot than non-white officers, but a previous study of police shootings in Chicago for the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology found that black officers were more likely to shoot than white officers. The studies were of different places and different times, so it’s impossible to generalize from them.

In addition, Wayne State University conducted a study in 2003 that assessed the impact of a department’s racial diversity on police-caused homicides and found that the ratio between minority and white police officers within a department “had no significant influence on levels of police violence.”

While it seems that the proportion of minority police officers doesn’t make a quantifiable difference in police shootings, it is hard to argue that more racially representative police forces—and even city councils—wouldn’t help build trust within a community, and perhaps avoid something like this in the future.