How the fish that built America could be poised for an eco-friendly comeback.

By Adia White / Illustrations by Hallie Bateman

This week, Pacific Standard looks at the global seafood industry — how it’s responding to class, consumer trends, and a new climate.

Fisherman Jim Price first noticed something was awry when he pulled up a striped bass that was too skinny and covered with lesions. It was 1997, and Price had fished the Chesapeake Bay many times before, but this was something new. After showing the body to a scientist at the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, he heard theories but no answers, and decided to get some himself.

Thereafter, Price made frequent appearances on the docks, using a pair of scissors to split open the stomachs of bass. He set up a laboratory in his home for weighing the fish and recording their percentage of body fat. Over a period of 20 years, Price says he dissected 15,000 fish. He found nearly all the stomachs of the bass were empty. The fish were starving because there weren’t enough menhaden.

Menhaden are filter feeders, the janitors of the Atlantic — they have always been around to clean up the mess.

You may know menhaden by a different name — “pogies,” “bunker fatback” — or you may have never heard of them at all. Menhaden are small, bony, oily fish that many people will never encounter at the grocery store. Menhaden are also a keystone species in the Atlantic, and when they disappear, bad things start to happen: The ocean becomes murky, and algae blooms spread unchecked. Menhaden are filter feeders, the janitors of the Atlantic — they have always been around to clean up the mess.

And now they’re not.

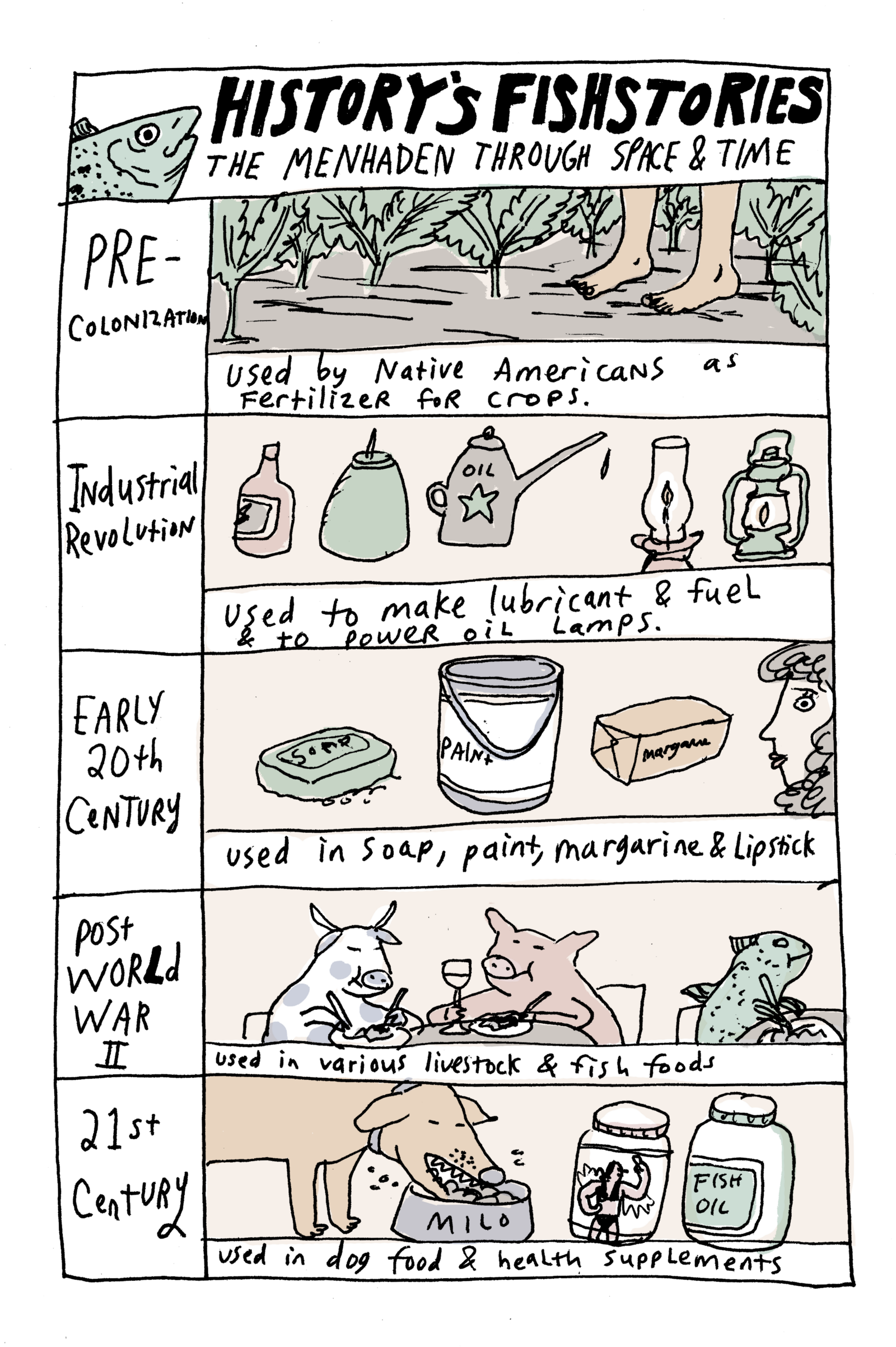

At least not in the numbers they once were. Before and during the early years of colonial settlement, Native Americans and colonists used whole menhaden to fertilize the soil. As late as the 1880s, menhaden oil was used in lamps. Because menhaden have been part of the American ecosystem for so long, we have good records of their populations over time. While menhaden are not technically an overfished species, scientists, historians, and fishermen nonetheless agree that menhaden are less abundant than they used to be — and their absence is leaving an unfilled void in the ecosystem.

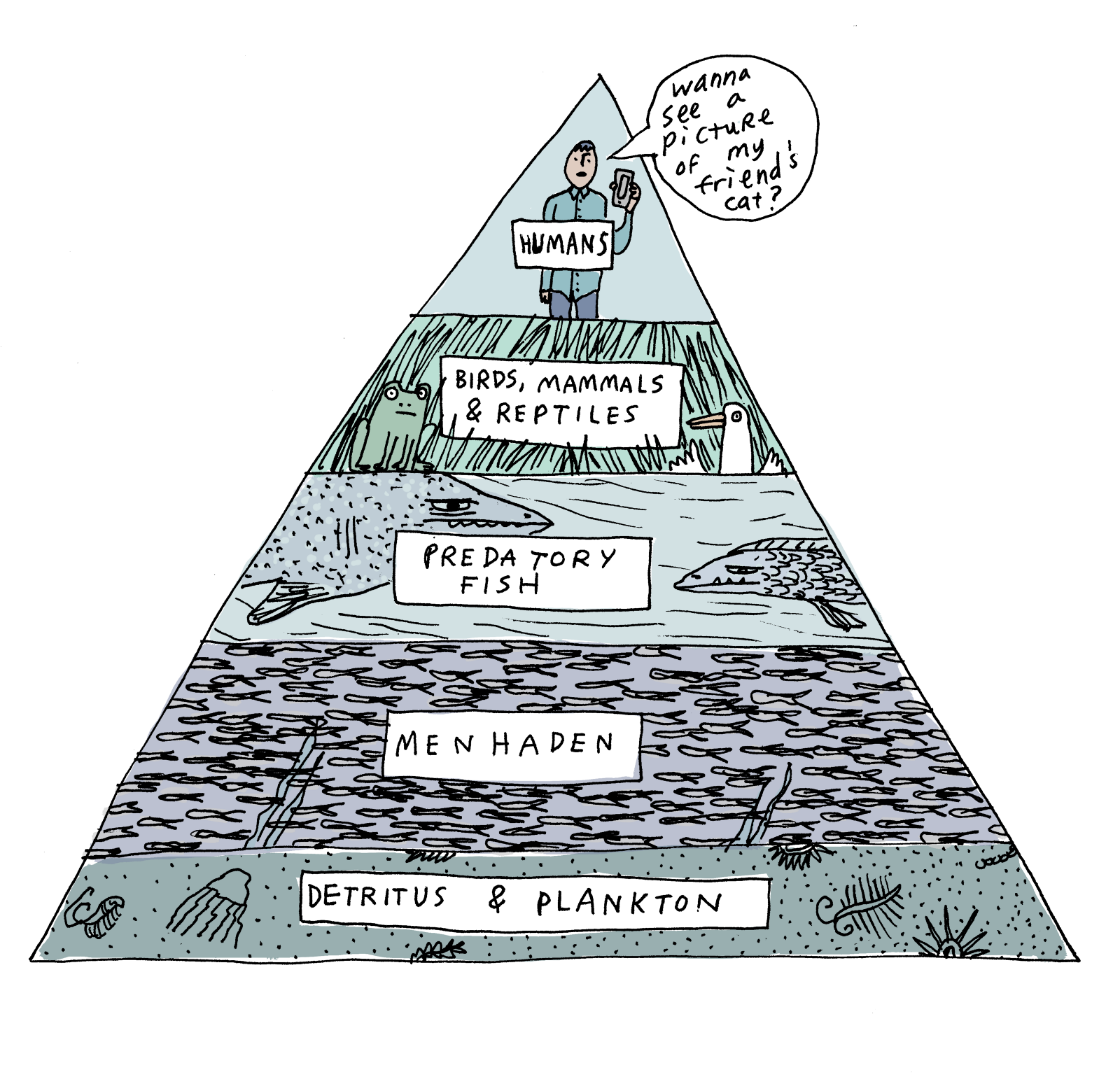

Menhaden are at the bottom of the food chain for a number of Atlantic fish.

Predator fish such as bluefish, striped bass, and bluefin tuna get nutrients from menhaden that they cannot get in other prey — in part because the menhaden is one of the few kinds of fish that are able to digest the cellulose in plants.

It’s not just that other fish need menhaden for food; menhaden also play an important role in cleaning the ocean. In his book The Most Important Fish in the Sea, historian Bruce Franklin says that an adult menhaden can filter 5,760 gallons of water in one day. This filtration ensures that sunlight penetrates to the bottom, allowing photosynthesis for aquatic plant life.

Menhaden play a crucial role in cleaning the ocean: An adult menhaden can filter 5,760 gallons of water in one day. This filtration ensures that sunlight penetrates to the bottom, allowing photosynthesis for aquatic plant life.

One of the major problems besetting the Atlantic today is hypoxia — a lack of oxygenation that causes oceanic dead zones. When fertilizers spread from farmland to the ocean, the excess nutrients cause algal blooms. After the algae consume what they can on the surface, they die and sink to the bottom of the ocean. Rotting takes oxygen. If too much of the oxygen is depleted, bottom feeders won’t have enough air to survive.

That’s why menhaden are so crucial to oxygenating the ocean. Menhaden arrive early at the scene to consume the algae, schooling and feeding in the Gulf of Mexico, where the Mississippi River deposits excess fertilizer from farms in Middle America.

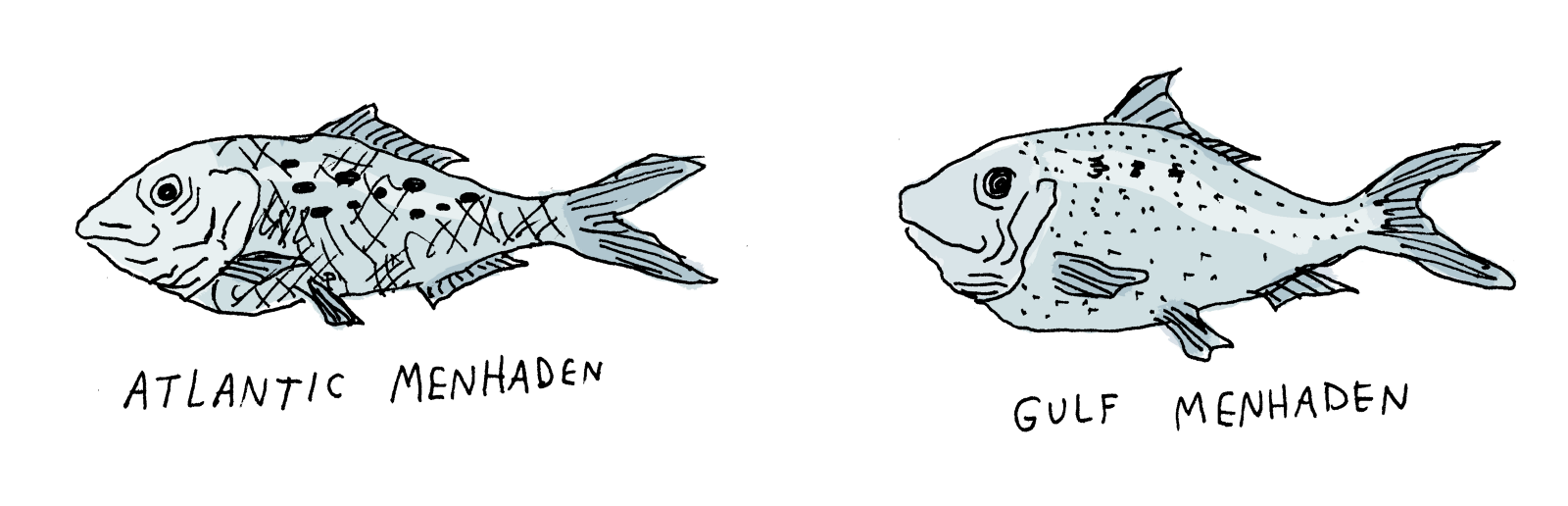

As a result, the majority of menhaden are caught in the Gulf. In 2014, around 845 million pounds were fished from the Gulf alone — and while menhaden fishing in the area hasn’t single-handedly caused the dead-zone, it may have contributed to its extent. As Franklin writes, “the menhaden come to eat the phytoplankton that are responsible for lethal algal blooms, but instead of being welcomed as a wonderful natural control mechanism, they are caught by the billions and turned into industrial commodities.”

Today, the Gulf of Mexico is home to the second largest dead-zone in the world, the area of which equals the size of Rhode Island and Connecticut combined.

Looking out into the Atlantic today, you won’t see schools of menhaden stretching into the horizon, but things were very different in the 1600s. When John Smith first sailed to America he came across schools of fish several miles long. In his 1608 journal, he writes: “There were an abundance of fish, lying so thick with their heads above the water that for want of nets (our barge driving around them) we attempted to catch them with our frying pan; but we found it a bad instrument to catch fish with.” John Smith didn’t have a name for the fish at the time, for there were none in England. Historians suspect that these fish were schools of menhaden.

According to Franklin, it was Smith’s descriptions of abundant oceanic life that drew some of the first colonists to America. Once the colonists arrived, it was menhaden again that allowed them to survive here. Squanto, a Patuxet Native American, showed the English settlers how to plant a corn seed with the body of a fish, increasing the productivity of the crop in the inhospitable and rocky northeastern soil. The fish was called munnawhateaug, meaning fertilizer. The Native American name has since been adapted to menhaden.

Restoring the menhaden to historic numbers won’t magically cure our dead zones, filter out all of the pollution, or suddenly cure the striped bass. But the menhaden could do more for these problems than any other single solution.

In 1850, a more commercial use was discovered, when a fisherman’s wife in Blue Hill, Maine, discovered how to extract oil from menhaden. She called the extract “fish water” and sent a sample to a merchant in Boston. Twenty years later, the sale of menhaden oil exceeded that of whale, cod, and seal oil combined. It oiled the machinery of the American Industrial Revolution and lit the streets of the first East Coast cities. The remaining carcasses of the menhaden were dried and crushed into fertilizer and then shipped across the country. Before the dawn of the 19th century, menhaden became a staple of American industry, both agricultural and otherwise. That is until 1879, when they disappeared. Due to industrial overfishing the menhaden population collapsed. The economic repercussions were devastating, especially to local fishermen.

That year there were riots. A menhaden reduction plant burned down in Reedville, Virginia. Arson was widely suspected, at the hands of small-scale fishermen. In 1880, G. Brown Goode wrote a book about the menhaden decline: “More than 40 steamers went out into the Gulf of Maine in July. To return in a few weeks without wetting their nets.”

The population eventually recovered. Menhaden are prolific breeders and aren’t likely to go extinct due to overfishing. Unfortunately, the fish that rely on them are more vulnerable.

The menhaden fishery is the second largest in the United States; the majority are caught in the Chesapeake Bay and the Gulf of Mexico. Though you won’t find it on your plate, it is almost everywhere else: in livestock feed, fertilizer, farmed fish food, pet food, and fish oil dietary supplements.

The Atlantic State Marine Fisheries Committee assesses the health of the menhaden population from Maine to Florida. It maintains that menhaden are not overfished in this region.

The Committee, however, is still working on how to address the importance of menhaden as food for other species. Marine scientist Thomas Miller at the University of Maryland says this needs to be changed. “The current reference points focus on the impact of the fishery on menhaden, they don’t consider the effects of menhaden on the larger ecosystem,” he says.

By 1870, the sale of menhaden oil exceeded that of whale, cod, and seal oil combined. It oiled the machinery of the American Industrial Revolution and lit the streets of the first east coast cities.

This is a crucial element.

If we assess the sustainability of the menhaden by looking to the health of the ocean they support, the situation appears far more dire. Recent surveys from the Maryland Department of Natural Resources found that 60 percent of striped bass in the Chesapeake Bay are infected with mycobacteriosis, a bacterial infection that can cause lesions and death in fish. Bass feed largely on menhaden and recent autopsies show that many are starving. Scientists are beginning to suspect the bass are more prone to bacterial disease because they are malnourished, and that they are malnourished because there are not enough menhaden.

The menhaden population may be healthy enough to support itself, but today the species doesn’t seem sufficient to feed the predator fish that rely on them. This problem isn’t unique to the menhaden. Most fisheries are managed with a single-species approach, meaning that the overseers do not consider the ecological role of the fish — just how many they can catch without destroying the species. When we don’t consider the domino effect, we leave too much room for ecological disasters.

In recent years, the menhaden question has caused a fuss that is changing the way the Atlantic menhaden fishery from Maine to Florida is managed. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association and the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Committee are working on a new management strategy that takes its ecological role into account. The plan should roll out some time this year or in 2017. Restoring the menhaden to historic numbers won’t magically cure our dead zones, filter out all of the pollution, or suddenly cure the striped bass. But the menhaden could do more for these problems than any other single solution. As we see throughout U.S. history, the menhaden are not to be underestimated, and what they’ve shown us in the Atlantic could serve as a lesson on the importance of conserving small forage fish worldwide.

||