A lot of the discussion about next month’s elections has focused on the United States Senate (Republicans may take control) and the House (Republicans may pick up a few seats). But what about state legislatures? After all, that’s where a lot of the major policy innovations have been occurring in recent years, on such issues as firearms access, abortion regulations, environmental rules, and so forth. A few seats shifting in the U.S. House probably won’t make much of a difference in public policy; a few state legislatures shifting control really will.

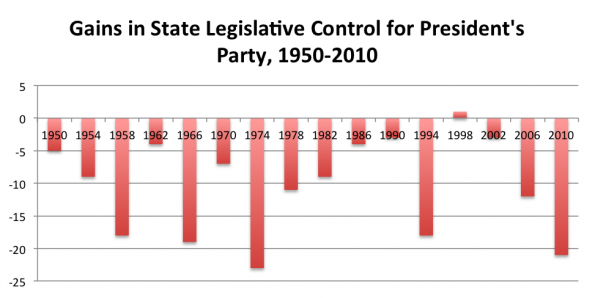

It turns out that the same factors that explain shifts in congressional control are at play in state legislative elections as well. (State legislative elections track congressional elections extremely closely.) As with congressional elections, the president’s party almost invariably loses state legislatures in a mid-term election. As the chart below shows, in mid-term elections since 1950, the president’s party lost control of state legislatures in every year except 1998. And the big losses track the major congressional wave elections—the post-Watergate blowout in 1974, Clinton’s big losses in 1994, Obama’s “shellacking” in 2010, etc. (Data come from Tim Storey and Carl Klarner.)

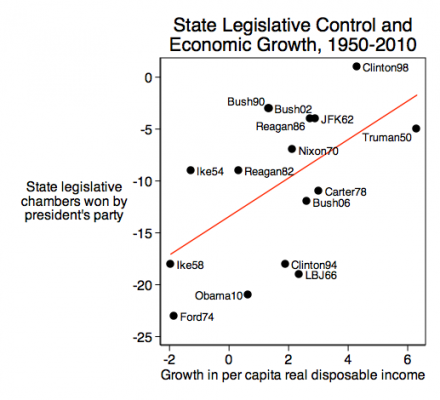

Also like congressional elections, state legislative outcomes tend to turn on a handful of national political factors. Chief among these is economic growth. The chart below shows the relationship between growth in real disposable income (from the middle of the year before the election to the middle of the election year) and the number of chambers lost or won by the president’s party. The data points are labeled by the incumbent president and year. This is a pretty strong relationship, suggesting that while the president’s party will almost always lose chambers, it can mitigate those losses during periods of strong economic growth. Incidentally, that economic growth figure today is 1.8 percent, which is commensurate with a little more than 10 chambers lost by the president’s party.

The popularity of the president is also important here. Roughly every two points the president gains in his approval rating, he saves a state legislative chamber for his party. This is a large part of the reason Bill Clinton and George W. Bush were able to avoid major losses for their parties in state legislative elections of 1998 and 2002, respectively.

It’s also important to consider exposure—how many chambers the president’s party currently controls. Democrats held 58 chambers going into the 2010 elections, including some very competitive ones that were relatively easy pick-ups for Republicans during a strongly pro-Republican tide. Democrats only hold 40 chambers this year; it’ll be harder for Republicans to pick up as many chambers as they did four years ago.

So putting all these variables together into a regression equation yields a prediction that Republicans will pick up roughly 13 state legislatures this year. Now, to be sure, that’s a pretty antiseptic forecast, ignoring some important state-by-state details. And it doesn’t really tell us just which chambers are most likely to flip, although any list would have to include chambers like the senates of Colorado, Nevada, Iowa, and Oregon, where Democrats only hold the majority by one or two seats.

But what we know about state legislative elections suggests that they turn strongly on the national political environment, and the political fates of thousands of state legislators next month turns on voters’ perceptions of Barack Obama and the national economy. If history is any judge, Republicans will emerge from the election with a greater ability to mold state-level policy and affect the lives and livelihoods of state residents, even if those residents aren’t thinking about this when they cast their votes.