The conviction of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev has renewed debate about the death penalty. Convicted on all 30 charges in one of the worst domestic terrorist attacks in American history, Tsarnaev would certainly meet the criteria for the death penalty. The question, then, is whether most Americans want Tsarnaev to die at the hands of the state.

“My heart goes out to the families here, but I don’t support the death penalty,” Senator Elizabeth Warren said last week, per the Boston Globe. “I think that he should spend his life in jail. No possibility for parole. He should die in prison.”

While Warren may be a polarizing figure, on the death penalty, an increasing number of Americans—both Democratic and Republican—agree with her. Since 1994, Gallup finds that death penalty support among Democrats has tanked 26 points; just 49 percent of Democrats support the death penalty today, compared to 75 percent in 1994. Republican support has even dropped by nine points (76 percent support today vs. 85 percent in 1994).

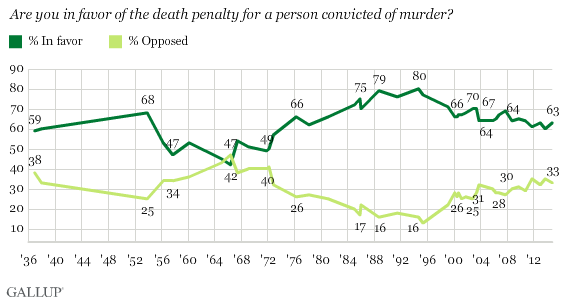

Polling on the death penalty is actually one the longest-standing questions in American history; Gallup has data going back to 1937. Support for the death penalty, it turns out, has fluctuated quite a bit, hitting a peak of 80 percent in the early ’90s. Over the last few years, however, there has been a substantial decline in support, allowing researchers to investigate how hardened beliefs can shift over a period of time.

The Boston bombing will be a test of America’s ethics, rather than America’s faith, in the fairness of our justice system.

In 2001, legal professors Samuel R. Gross and Phoebe C. Ellsworth proposed that near-unanimous support for the death penalty in the ’90s actually helped bring the issue into public debate in a way that would allow people to change their minds. New scientific information—specifically the use of DNA in acquitting defendants—re-framed the issue that gave citizens a way to “save face” in attitude changes.

“Innocent people have been released from death row for decades and there is no evidence that the system for deciding capital cases has deteriorated recently,” the two wrote. “The problem is not new; what is new is that people notice and care. It has helped that the use of DNA identification in a small number of cases has made this issue look new and scientifically undeniable, but the main catalyst is timing.”

While general opposition to the death penalty may apply to policy more broadly, it’s hard to know if this will be the case for the Boston Bomber. The overwhelming reason why most people support capital punishment is moral, a belief that justice should be applied in reciprocity—the “eye for an eye” philosophy. Only seven percent say the main reason for supporting capital punishment is as a deterrent against crime.

The Boston bombing case will be a test of America’s ethics, rather than America’s faith, in the fairness of our justice system.