After years spent years gathering data to shed light on how debt collectors use the courts, here are the most important lessons learned about a tactic that affects millions.

By Paul Kiel

(Photo by Matt Cardy/Getty Images)

Millions of Americans live with the possibility that, at any moment, their wages or the cash in their bank accounts could be seized over an old debt. It’s an easily ignored part of America’s financial system, in part due to a common attitude that people who don’t pay their debts deserve what’s coming to them.

A couple of years ago, we set out to find out more about the growing use of the courts to collect consumer debts. How many lawsuits are filed? Who is filing them? Who is getting sued?

The suits are filed in state and local courts, and many states rely on antiquated systems or only keep data at the county level. We ultimately collected what details we could from a variety of states and large, urban counties. Then, we wrote a series of stories sharing what we found:

- Four million Americans had their wages garnished over consumer debts in 2013, and workers earning between $15,000 and $40,000 a year were the most likely to experience a garnishment.

- Black communities are hit much harder by debt collection lawsuits than white ones, even in places where black households and white households have similar incomes.

- One subprime lender with stores nationwide was seizing pay from active-duty soldiers when they fell behind on overpriced loans. (The company subsequently went out of business.)

- Some public and non-profit hospitals use the courts to collect from patients who can’t pay their bills, even when those patients obviously qualify for financial assistance.

- Capital One sues its customers way more than any other bank and filed an enormous number of suits during the 2007–09 recession.

But there’s a lot more to understand about the rise of this legal tactic — one that continues to alarm judges who see it firsthand.

“It seems to me that over the years I’ve become less of an authentic arbiter of disputes and more a processor of paperwork,” said Steven McMurry, a justice of the peace in Phoenix, Arizona, who has been presiding over such cases since 1998. “The thing that gets me so upset, I see all these cases and I question whether there might be some valid defense.”

Here are other important lessons we’ve learned:

Debt Buyers Are Primarily Responsible for the Rise in Lawsuits

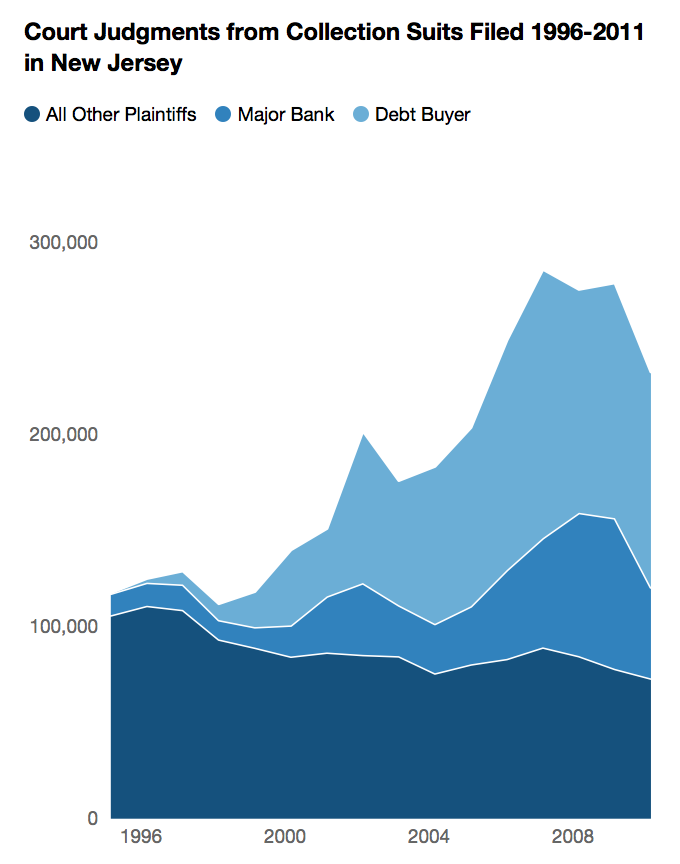

So, what’s changed to trigger these suits? The most important difference since the late 1990s is relatively simple: the emergence of debt buying. Take New Jersey for example:

(Source: ProPublica analysis, state court data from New Jersey’s Special Civil Part, which has jurisdiction over amounts up to $15,000.)

In 1996, there were around 500 court judgments in New Jersey from suits filed by debt buyers. By 2008, that number had reached 140,000. It’s dipped since then, but the change over time is obvious. Debt buyers dominate the docket in New Jersey’s lower level civil court: In 2011, they accounted for 48 percent of the court judgments. And from 2001 through 2011, they obtained more than one million court judgments in New Jersey alone.

For the most part, debt buyers purchase defaulted credit card accounts, typically for a few pennies on the dollar. Starting in the late ’90s, the industry began a period of rapid growth and then exploded in the middle of the last decade. That led to a sharp spike in suits, many of them by smaller debt buying companies that have since gone out of business.

The industry is now dominated by several large companies. The largest, Encore Capital Group, typically sues through its subsidiary, Midland Funding, LLC. In 2015, Encore collected $1.2 billion nationally from consumers, more than half of that through the courts, according to its most recent annual filing.

Data from courts all over the country show the same growth of debt buyers’ role in the courts, and in most courts, we found that debt buyers filed more suits than any other type of plaintiff.

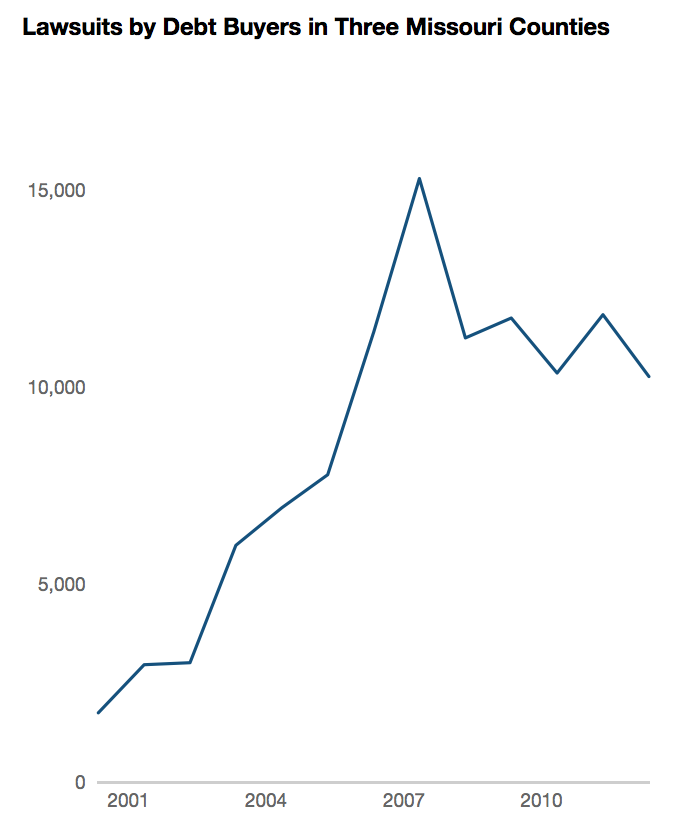

Here is what that growth looks like in three large Missouri counties for which we had data going back to 2001:

Note: The three counties are Jackson County (Kansas City), St. Charles County (suburban area of St. Louis), and the City of St. Louis. (Source: ProPublica analysis, state court data from Associate Circuit Court, which has jurisdiction over amounts up to $25,000.)

Debt buyers accounted for 42 percent of debt collection suits in these counties in 2013.

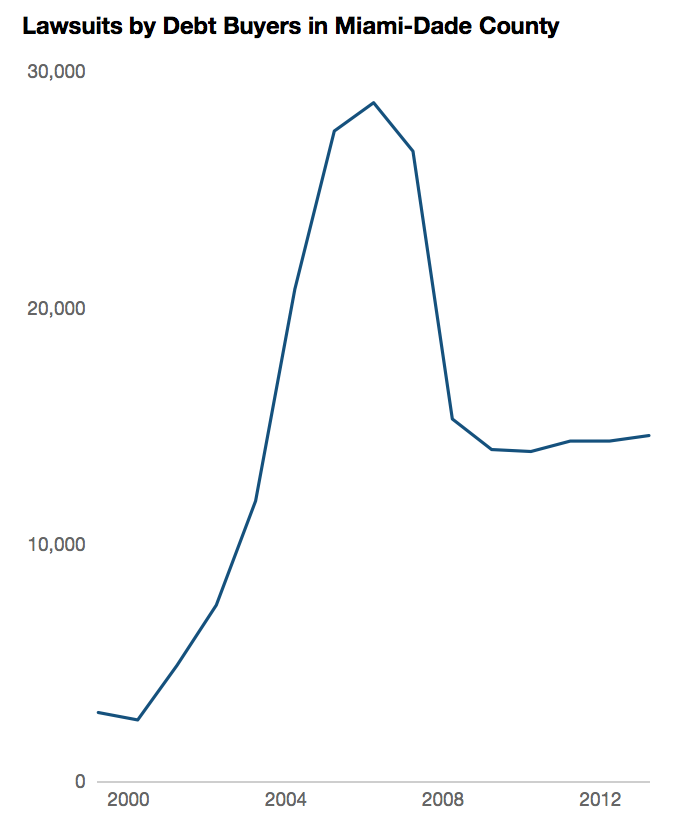

And here is Miami, Florida, where the explosion in suits in the middle of the last decade was even more pronounced:

(Source: State court data, all jurisdictions, ProPublica analysis)

Plaintiffs Are Represented by Attorneys, Defendants Largely Are Not

In 2011, Pressler & Pressler, the biggest collections law firm in New Jersey, obtained at least 76,000 judgments for its clients, primarily the debt buyers Encore Capital and New Century Financial Services. In about 69,000 of those suits, the firm used the same attorney: Ralph Gulko.

How does one person file more than 69,000 lawsuits in a year? According to a deposition Gulko gave as part of a lawsuit against his firm, he’d sit at a desk with two computer screens. On one screen would be a lawsuit, already prepared by the firm’s support staff and ready to be filed, and on the other, a summary of basic information about the case. If Gulko saw no problems, he’d electronically sign it and a Pressler employee would electronically file it.

The firm’s records showed that it took Gulko as little as four seconds to review a suit, and he did between 300 and 400 — sometimes as many as 1,000 — per day.

Last month, the federal Consumer Financial Protection Bureau ordered Pressler to pay a $1 million penalty for having filed lawsuits based on unreliable information. Pressler consented to the action, which required the firm to institute a more robust review process, but said in a statement that its process had always been sufficient to prevent filing errors.

But if there are any mistakes, it’s up to the debtors to spot them — without the aid of an attorney. In about 99 percent of Pressler’s 2011 suits, defendants didn’t have attorneys, according to our analysis. This is typical of collection suits. In 2013 in New Jersey’s lower level court, for example, more than 97 percent of defendants in debt collection cases lacked attorneys.

In Missouri that same year, about 91 percent of debtors faced suits without an attorney. Those who did have lawyers, we found, typically came from richer, whiter neighborhoods. Looking at suits from 2008 through 2012 in the St. Louis area, residents of lower-income, mostly black neighborhoods had attorneys in 4 percent of cases, while residents of upper-income, mostly white neighborhoods had them in 14 percent of cases.

Not surprisingly, suits against residents of the lower-income, black neighborhoods were much more likely to result in judgments (69 percent) than suits against residents of upper-income, white neighborhoods (53 percent).

It Matters a Lot Where You Live

Our story on Nebraska’s high volume of suits showed that key factors, such as the cost of filing a suit, can cause a huge difference in the number of collection suits filed from state to state. These differences between court systems haven’t received much attention, but they should. They result in vast disparities for poor debtors across the country.

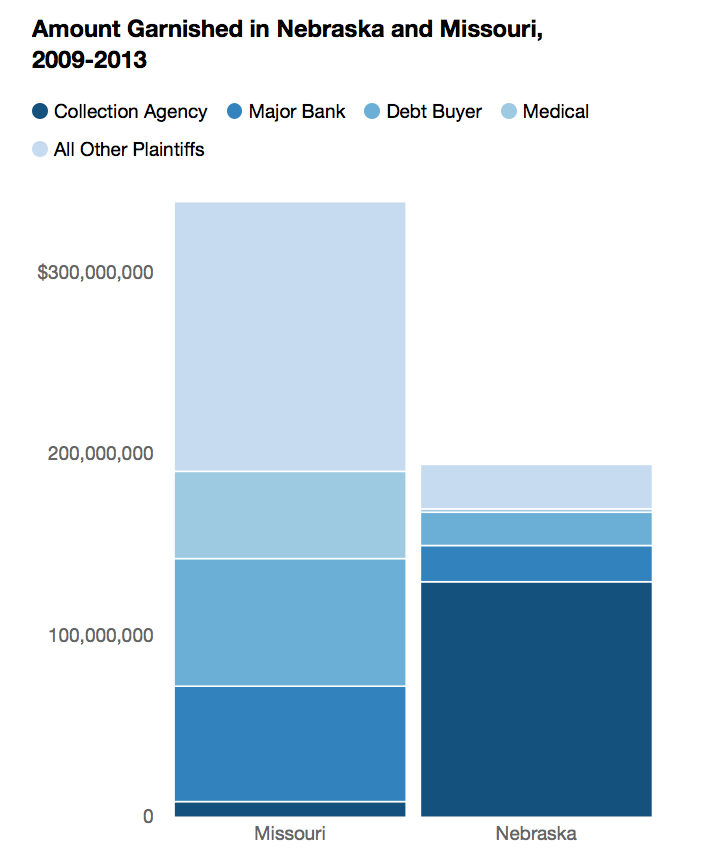

Below is a comparison of garnishments — money seized from debtors’ paychecks or bank accounts — in Missouri and Nebraska:

(Source: ProPublica analysis, state court data. For Nebraska, data includes cases filed in county courts, which have jurisdiction over suits up to $53,000. Missouri data is from Associate Circuit Court, which has jurisdiction over amounts up to $25,000.)

Keep in mind that Nebraska has a population less than one-third as large as Missouri’s. During this time period, $56 was garnished for every resident of Missouri. In Nebraska, it was $103. The difference is due to the more active role of collection agencies in Nebraska, which garnished $130 million over these years.

Nebraska’s higher number of suits can’t be explained by obvious differences such as a larger proportion of low-income families or more delinquencies. And, as Annie Waldman and I reported last year, a disproportionately high number of debt collection lawsuits are filed against black people, but only about 5 percent of Nebraska’s population is black.

So it’s clear that where debtors live matters at least as much as what race they are. Our study last year compared black and white neighborhoods in three different cities, and we found that, in the same city, the mostly black neighborhoods had twice as many court judgments as the mostly white neighborhoods, even when accounting for income.

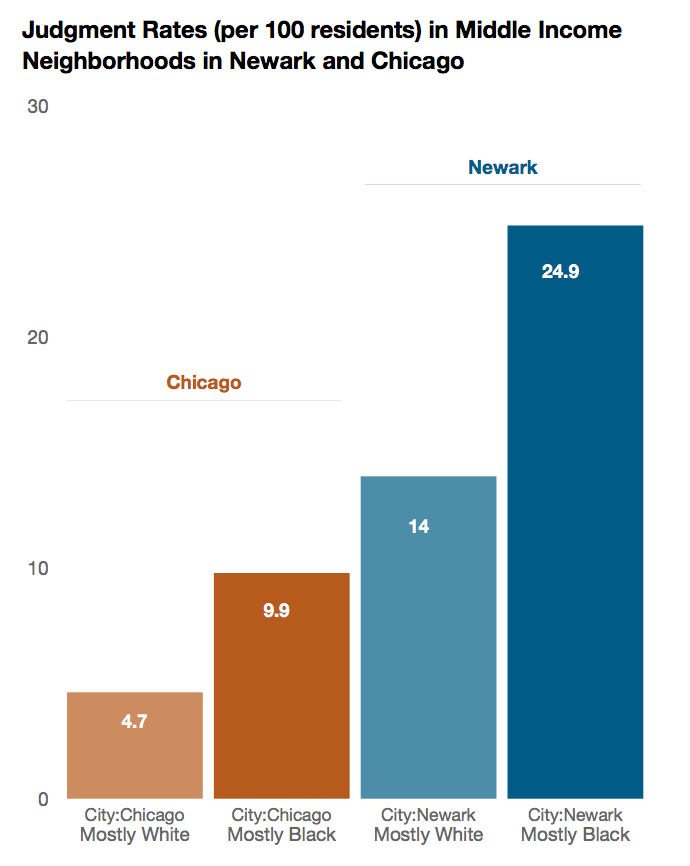

But compare across cities and the picture looks different. Here, for instance, is a comparison of judgments in middle income neighborhoods in Newark and Chicago, broken down by the racial make-up of the neighborhood where the defendant lived:

Note: Data includes judgments obtained through debt collection cases filed 2008–12. We defined middle income here as annual household income between $47,000 and $74,000. (Source: ProPublica analysis, state court data. Newark data is for Essex County, New Jersey, Special Civil Part; Chicago is for Cook County, Illinois, Circuit Court)

It’s more than three times as expensive to file a lawsuit in Cook County, where Chicago is located, than it is in Essex County, New Jersey. Consequently, a lot more debtors are sued in New Jersey. We found a higher rate of court judgments in the mostly white neighborhoods around Newark than we did in the mostly black neighborhoods of Chicago at the same income level.

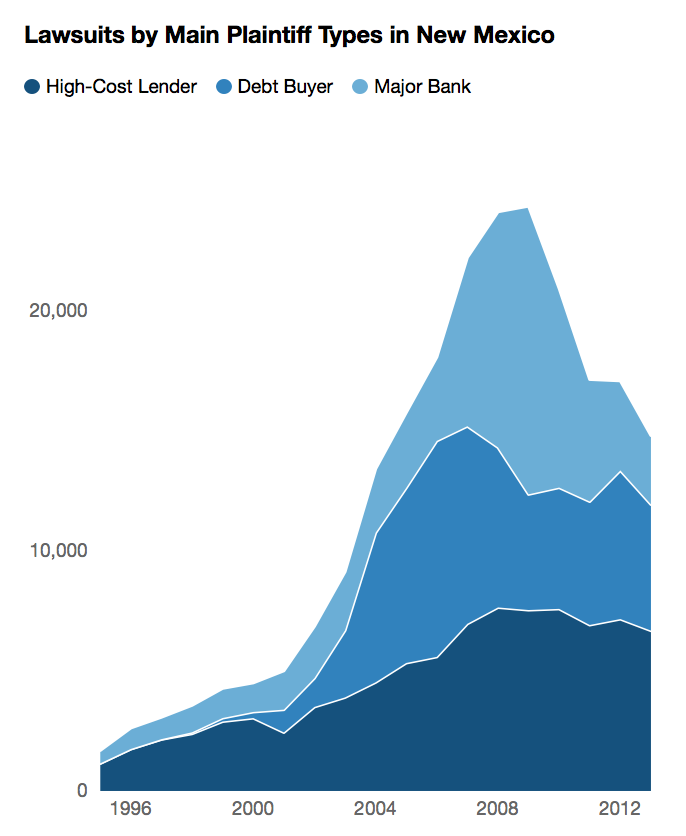

In Some States, High-Cost Lenders File the Most Lawsuits

Which types of companies file collection suits is also a reflection of state laws. In New Mexico, where there is no interest rate cap on installment loans, a large portion of suits are filed by these high-cost lenders:

Note: These three plaintiff types accounted for two-thirds of debt collection suits in 2014. (Source: ProPublica analysis, state court data from all relevant jurisdictions—district, magistrate, and metropolitan courts)

Most are filed by just a few companies: Your Credit and Noble Finance, both owned by the same man, Anthony Gentry. We wrote about Gentry in 2013, because his companies also file thousands of suits in Oklahoma and Missouri. The loans routinely come with annual interest rates above 100 percent.

“The loan information is fully disclosed to the borrower, they leave the branch office with money in hand and knowing their payment expectations,” he told us. “Yet when they don’t pay us back — you paint us as the bad guys.”

In Las Vegas, high-cost lenders also dominate the lower level court: From 2004 through 2014, they filed a total of 150,000 lawsuits there.

Some Plaintiffs Just Keep Suing, Even When the Economy Improves

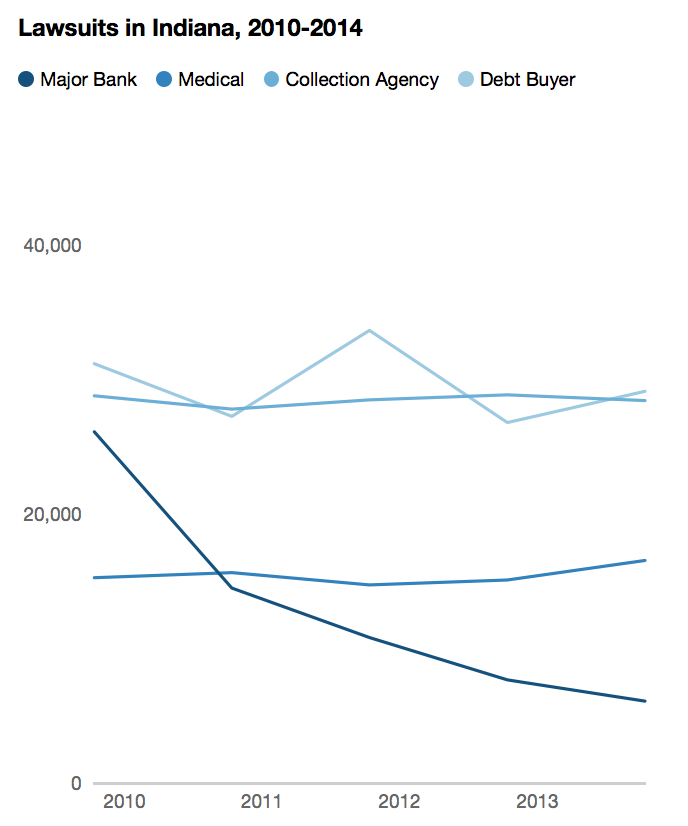

The finances of some debtors don’t improve along with the economy, making them targets of collectors in good times and bad. You might expect collection lawsuits to go up when the economy tanks and go down as it improves. That’s generally what happened with big banks and credit card debt. But not so for debt buyers, high-cost lenders, or those suing over medical debts.

Here’s a graph showing suits in Indiana courts by the four most common plaintiffs:

Note: Data includes small claims court and circuit courts for about two-thirds of the state. (Source: State court data, ProPublica analysis)

The collection agencies in Indiana primarily bring suits over medical debts. And those suits labeled “medical” in the graph above are predominantly filed by hospitals.

The consistency of these suits suggests that they target a population that has trouble recovering from debts even after the economy has improved.

Collectors Frequently Clean Out Debtors’ Bank Accounts

One of the most aggressive measures a debt collector can take is to seize cash from a debtor’s bank account. Data from Missouri allowed us to examine how often companies, armed with court judgments, took this step — and how little was left for them to take.

It wasn’t for lack of trying. Plaintiffs in Missouri tried to garnish debtors’ bank accounts at least 59,000 times in 2012. Most of the time, they got nothing. That might’ve been because the account was empty, or because collectors had the wrong account information. Still, they were successful 13,000 times.

About 60 percent of the time, there was less money in the account than the debtor owed. When that happens, the plaintiff can take every penny in the account.

Collectors typically got around $500 per garnishment, we found. But for those that zeroed out an account, the median was $350.

Still, it added up. From 2009 through 2013, plaintiffs in Missouri took at least $48 million from debtors’ bank accounts — about 14 percent of the $339 million garnished during those years, mostly through debtors’ wages.

The Threat of Garnishment Persists for Many Years

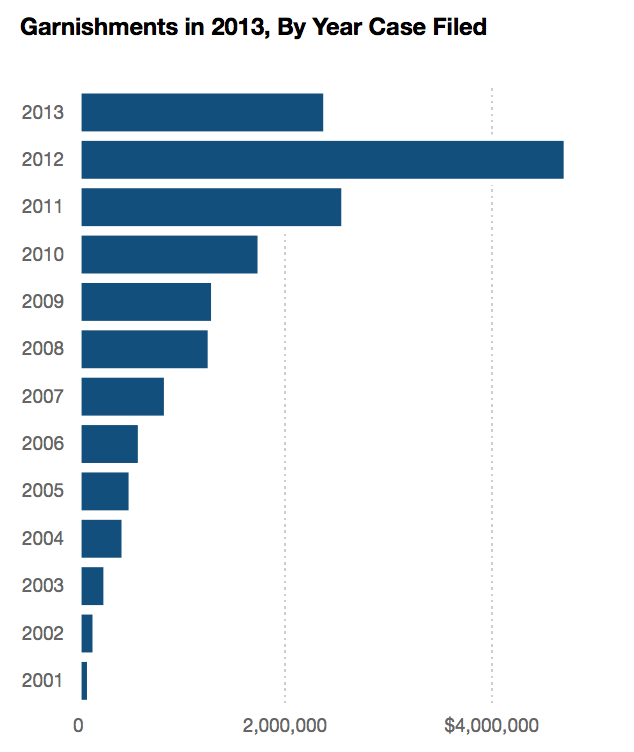

Finally, and perhaps most toxically for debtors, court judgments from collection suits can be near-permanent. In Missouri, a judgment is valid for 10 years and can be renewed for another 10. The plaintiff can seek to garnish a debtor’s wages at any time.

The graph below shows the long tail of garnishments in three Missouri counties. In 2013, plaintiffs garnished a total of $17 million, but only about 14 percent of that was from cases actually filed in 2013. A quarter came from suits filed in 2008 or earlier.

Note: The counties are the same three as above: Jackson County (Kansas City), St. Charles County (suburban area of St. Louis), and the City of St. Louis. (Source: State court data, ProPublica analysis)

So What Can Be Done?

No one is counting, and someone should. On the state level, policymakers are flying blind. They have no way of comparing the number and types of suits in their state to others. On the national level, major companies that fill the nation’s courts with lawsuits don’t get the scrutiny they otherwise might.

We listed a number of potential reforms last year, and those are definitely still applicable here. Most centrally, the last federal law to limit garnishments was passed in 1968. It was inadequate to start with and is now clearly out-of-date, consumer advocates say: Overhauling that law to set a more reasonable limit on wage seizures (now at 25 percent of after-tax income) and setting some limit (there’s currently none) on bank account garnishments would make a big difference.

In December, Missouri’s attorney general suggested a number of reforms to make the process fairer to debtors. The collection industry supported the measures, suggesting that some commonsense changes can be easy to agree on.

||

This story originally appeared on ProPublica as “So Sue Them: What We’ve Learned About the Debt Collection Lawsuit Machine” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.