A battle against leisure is unfolding. In America, it’s a war that has been raging since the Puritan age.

Though recently American leisure time has appearedto rise, the averages are skewed by undereducated and lower-income men, who are likely “unemployed or underemployed,” as the Washington Post has noted. Work-life balances are abominable when compared to other developed countries. And the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that the “average American” is actually working “one month” more a year than he or she was in 1976.

But Sunday, the weekend day that even Puritans blocked off for worship and rest (a Puritan poet once pondered “over whether closing a stable door that was blowing in the wind constituted an act of work which would profane the Sabbath”), is also beginning to look more and more like just another day of the work week.

It seems that even the sacrosanct tradition of once-a-week existential dread, the anxious pulse that some have called the “Sunday blues,” has recently receded amid the constant onslaught of email, dynamic I-choose-for-myself-which-seven-hours-of-programming-to-watch television, and encroaching publishing schedules, as John Herrman recently noted in The Awl.

Will Sundays, as we’ve known them, soon simply disappear? Evidence from Canada suggests that this full-scale erosion is already further along than we may think. Behaviorally, at least, the data support the theory that Sundays, once Western civilization’s weekly beacons of idleness, are becoming ever-more harried. Given the trend lines, it’s pretty safe to assume some form of the same phenomenon is occurring in the United States.

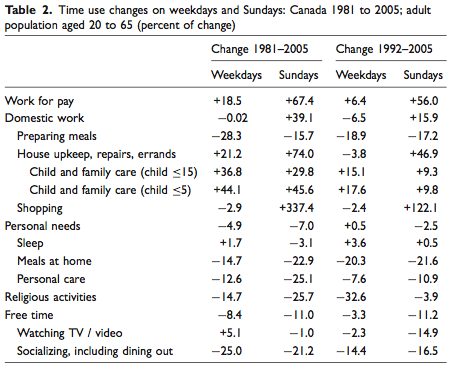

In the latest issue of Time & Society, University of Waterloo leisure studies professor Jiri Zuzanek compared behavioral and emotional data (from national surveys and smaller ones carried out by his own team) about Sundays collected in the mid-1980s to that of the mid-2000s. Here are some of the disturbing results:

[I]n 2005 adult Canadians spent 67% more time on Sundays working for pay than they did in 1981 – 106 minutes compared to 63 minutes. Time spent working around the house, caring for children and shopping increased on Sundays from 2.9 hours in 1981 to 4.0 hours in 2005. Of domestic obligations, shopping expanded the most – from less than 10 minutes in 1981 to 43 minutes in 2005. House upkeep rose from 48 minutes to 73 minutes, and errands from 16 minutes to 38 minutes. …

In 1985, 68% respondents felt free to do what they were doing on Sundays. In 2003, the corresponding figure was 58%. The number of Sunday episodes when respondents felt that they ‘had to do’ what they were doing grew from 18% in 1985 to 22% in 2003.

All the bad categories added time, and all the enjoyable ones lost.

(Chart: Time & Society)

As the chart above illustrates, the gains in convenience, from retail store hour expansions, for example, don’t appear to be making weekdays all that much easier either.

This radical Sunday transformation may have significant philosophical implications. Emile Durkheim, according to Zuzanek, believed that the distinction between weekends and weekdays was a significant one. It allows us to separate the “ordinary and the extraordinary, the sacred and the profane.” Or, in other words, it’s difficult to tolerate the dreary stream of TPS reports, tchotchkes, and general malaise without anticipation of any keg parties, computer smashing, money laundering, or whatever other dark weekend occupation you deem appropriate. As Zuzanek notes, Russian sociologist Pitirim Sorokin advanced Durkheim’s work further: “If there were neither the names of the days nor the weeks, we would be liable to be lost in an endless series of days – as grey as fog – and confuse one day with another.” How do we know what to do when it’s all the same? We could soon be witnessing a rip in the fibers of the “socio-cultural” time space continuum.

The most disturbing thing about this weekday behavioral encroachment is that it hasn’t precipitated a drastic change in the “emotional texture” (or the way you “feel” about a day) of Sundays. Canadians, at least, seem happy to embrace the rapidly declining status quo:

Respondents surveyed in 2003 continued to enjoy Sundays at a level not very different from 1985. Behaviourally, Sundays are today more constrained and more like the rest of the week, but we do not seem to mind. Survey research has shown that, generally, people tend to enjoy the things they are doing. To make the best of one’s life is natural. In a way, this serves as a self-defence mechanism. Life becomes miserable when we continuously dislike what we are doing. Economic analyses suggest that the net gainers of shopping and service deregulation were large retail chains, but the removal of shopping restrictions on Sunday met with popular support in most countries.

How can we stop the weekday from swallowing Sunday without even recognizing that it’s taking a bite? This failure of perception is perhaps a nuanced symbol that we are entering a new epoch. We are edging ever closer to a machine-tethered, work-chained, gruel-fed world governed by corporate automatons. In fact, the depressing implication of Zuzanek’s study, which didn’t even account for the more recent market saturation of smartphones, is that we may have already arrived. “Perhaps not only the days of the week became ‘grey,’ but so did we,” he concludes.