In a could-have-been major ruling on gun control last week, the Supreme Court had the opportunity to side with gun rights activists but instead backed Congress, upholding a provision in gun-control legislation that makes it a federal crime to buy a gun for someone else.

They heard an appeal from one Bruce James Abramski Jr., a former police officer fired for allegedly stealing funds during an investigation, who bought a gun for his uncle. His plan was to take advantage of his expired law enforcement identification to get a discount on a gun on his uncle’s behalf. Abramski’s intent to make the purchase on behalf of his uncle was clear: The uncle sent him a check before Abramski made the purchase, which he cashed only after buying and transferring the gun to his uncle.

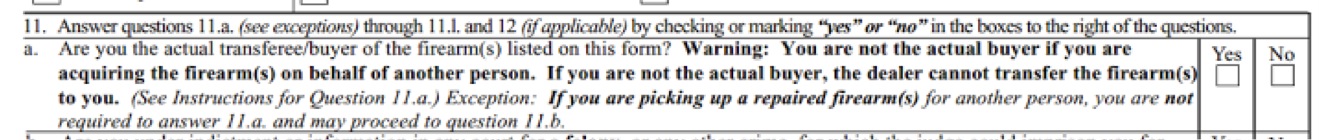

The problem is, buying a gun for someone else is illegal, and so is lying about it to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms on the federal form you have to complete when making a purchase. Abramski challenged his conviction; he argued that only the eligibility of the person buying a gun matters.

The question the Court considered was simple: Can Congress make it a federal crime to buy a gun for someone else and lie about it? Abramski and innumerable conservatives argued that gun-control legislation should only regulate who can buy a gun, not the transfer of a gun from one lawful owner to another. Five Justices said it’s clear the law’s purpose is to keep guns out of certain hands—felons and the mentally ill, for example—and that the provision prohibiting Americans from buying a gun for someone else clearly contradicts congressional intent.

IT’S A CURIOUS HOLDING for a Court that has disregarded clear congressional intent twice this month. In a case challenging a U.S. Customs and Immigration Services policy that sends the children of visa applicants who reach the age of 21 before the visa is granted to the back of the line, a group of congressmen—including Senators John McCain, Orrin Hatch, Diane Feinstein, and Chuck Schumer—told the Court that the intent behind the Act was to keep families together. But the Court ruled for USCIS anyway. (In her noteworthy dissent, Justice Sotomayor catalogued a host of reasons the convoluted ruling contradicts Congress’ purpose and the text of the statute.)

In a second case decided 7-2, the Court seized on semantics in a ruling that allows states to let companies dodge liability for toxic spills and pollution. The federal statute in question, they said, only barred companies from hiding behind “statutes of limitation,” whereas the North Carolina law protecting the company in the instant case was a variation on the theme, a little-known type of tort legislation called a “statute of repose.”

Buying a gun for someone else lets the intended owner circumvent background checks and other requirements Congress placed on those buying guns from licensed dealers.

What’s weird about the ruling is that the practical effect of the two types of tort laws they’re distinguishing from one another is the same: After a certain number of years have passed, these companies get to walk away from environmental wrongdoing—even if they concealed the contamination and victims don’t begin to suffer the consequences until after their chance to sue has expired, as happened in Asheville.

By deciding that the state law trumps federal, the Court has given polluters in states with statutes of repose an incentive to cover up pollution instead of disclosing it—and perhaps even to pollute, since they can avoid paying damages if they can keep the damage secret long enough. Their ruling may also block a group of Marines and their families who were exposed to contaminated groundwater while stationed at Camp Lejeune from 1957 to 1987 from suing.

Even the North Carolina state legislature seemed to think the Court’s ruling kooky. One Republican state representative, an attorney, told a reporter that the legislature was “surprised” at the Court’s decision. Two others introduced legislation that would close the loophole, effectively restoring the right to sue for victims in pending and future cases. The N.C. House passed the “fix” bill quickly.

WHILE THE SUPREME COURT generated the conclusion called for by the statute in this case—the one gun-control advocates wanted—the vote was as close as gun-rights activists could have hoped, just 5-4. The liberal bloc of the Court—Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan—reached five only with the addition of Justice Anthony Kennedy, whose last vote on a gun-control case favored conservatives. The vote shows just how precipitous prospects for future gun-control laws may be at the High Court.

The Court’s decision merely maintains the status quo by preserving long-standing legislation. In other words, the Justices didn’t place any new limits on gun buyers. They just affirmed that buyers can’t act as middlemen, since buying a gun for someone else lets the intended owner circumvent background checks and other requirements Congress placed on those buying guns from licensed dealers. It’s a violation that’s usually only discovered in the course of investigating a connected crime. Abramski’s scheme, for example, came to light when he was arrested for robbing a bank. In the first six months of the 2014 fiscal year, there were just 42 prosecutions in which the lead charge was related to the provision in question.

In truth, it won’t be that hard for buyers like Abramski to get around this rule—provided they use common sense, and don’t commit a related crime. If Abramski had merely waited to collect a check from his uncle, for example, it would have been much harder for prosecutors to argue that he bought it to resell to his uncle. Had he waited, Abramski could claim he got tired of the Glock 19 quickly, didn’t like how it fired after taking it to the range, caught a case of buyer’s remorse, or needed the cash. That exchange could have been, as Justice Antonin Scalia might characterize it, just the legal transfer of a gun from one lawful gun owner to another.

While it’s possible that the decision will somehow renew interest in enforcing this provision more aggressively, it’s not likely to spur law enforcement and prosecutors to act any differently. Of course, for gun-rights advocates, it’s not the law at hand—it’s the principle of the matter.

In principle, the gun-rights movement and libertarian brethren suffered a real blow this week: If only by a one-vote margin, the Supreme Court has given Congress a tentative green light on gun control. If new statutes reasonably restricting gun sellers and owners from giving guns to those Congress says shouldn’t have them reach the Court—for example, closing the so-called “gun-show loophole”—they could be upheld the same way. This decision thus marks a big victory for gun-control advocates, one sorely needed and rightfully celebrated in the wake of high-profile shootings like that at Sandy Hook Elementary and amidst ongoing gun violence that demonstrate the need for stricter limits on gun ownership.