If the anti-Trump movement wants to learn from the 1960s, we need to be more honest about what activism meant back then.

By Malcolm Harris

Frank Smith, Bob Moses, and Willie (Wazir) Peacock at the S.N.C.C. office in Greenwood, Mississippi, 1963. (Photo: Civil Rights Movement Veterans)

As the resistance to President Donald Trump’s regime begins to organize and distinguish itself from the Democratic Party, it faces a question of tactics. Marches can be energizing, especially for newcomers, but when they don’t lead anywhere (in a larger sense), they can turn dispiriting. Property destruction — anarchists sometimes jokingly call it “smashy smashy” — gets media attention and can shut down a fascist recruiting party, but broken glass and fire sometimes scare the wrong people too. Even though we all agree on stopping Trump, can the resistance work together if we can’t decide on how to resist?

For a couple of decades, American left-wing organizers have settled into an uneasy accord called “diversity of tactics.” During the 1990s anti-globalization movement, warier organizations agreed not to condemn property destruction to the media (or to the authorities), as long as they had some plausible deniability. If a demonstration has endorsed a diversity of tactics, that’s supposed to mean that everyone agrees to a certain amount of participatory variation in the interests of unity. In practice, it usually means that some people might want to bloc-up and smash windows. The compromise has enabled real achievements (like slowing the blind spread of free trade), but this diversity of tactics has become unsatisfactory to everyone involved. At most demonstrations, the Black Bloc is too small to protect itself, and moderate marchers — some of whom have the experience to know better — are crying over broken windows. Now the first smashed Starbucks or looted convenience store or garbage can fire is the center of the action, for participants, the media, and the public. But the uneasy accord isn’t really headed anywhere, and the most vibrant actions (like the airport demonstrations) have been reactions.

What unified the Civil Rights Movement was not an ideology of hardcore Christian pacifism, but a determination to make change.

To go beyond diversity of tactics, a common impulse is to revisit the history of the Civil Rights Movement, but first I want to clarify the terms of this debate — and the history of the Civil Rights Movement. No one within a few standard deviations of the American left mainstream even contemplates the tactic of lethal offensive violence. “Diversity of tactics” doesn’t mean “anything goes,” and, unlike the right (whether we’re looking at the anti-government, anti-abortion, or standard hate-crimes faction), the left generally does not countenance murder. Like almost everyone else — including the government — leftists tend to think the rules are different for self-defense, but actively looking to hurt people is a no-go. Whenever a march gets a little bit rowdy, however, someone is quick to cite the dignified example of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement, as if that were a front man and his backing band. Critics who take up these talking points posit “non-violence” as a tactical spectrum between marching and peacefully getting arrested. Anything else, they worry, risks alienating the public. And, furthermore, breaking windows is wrong.

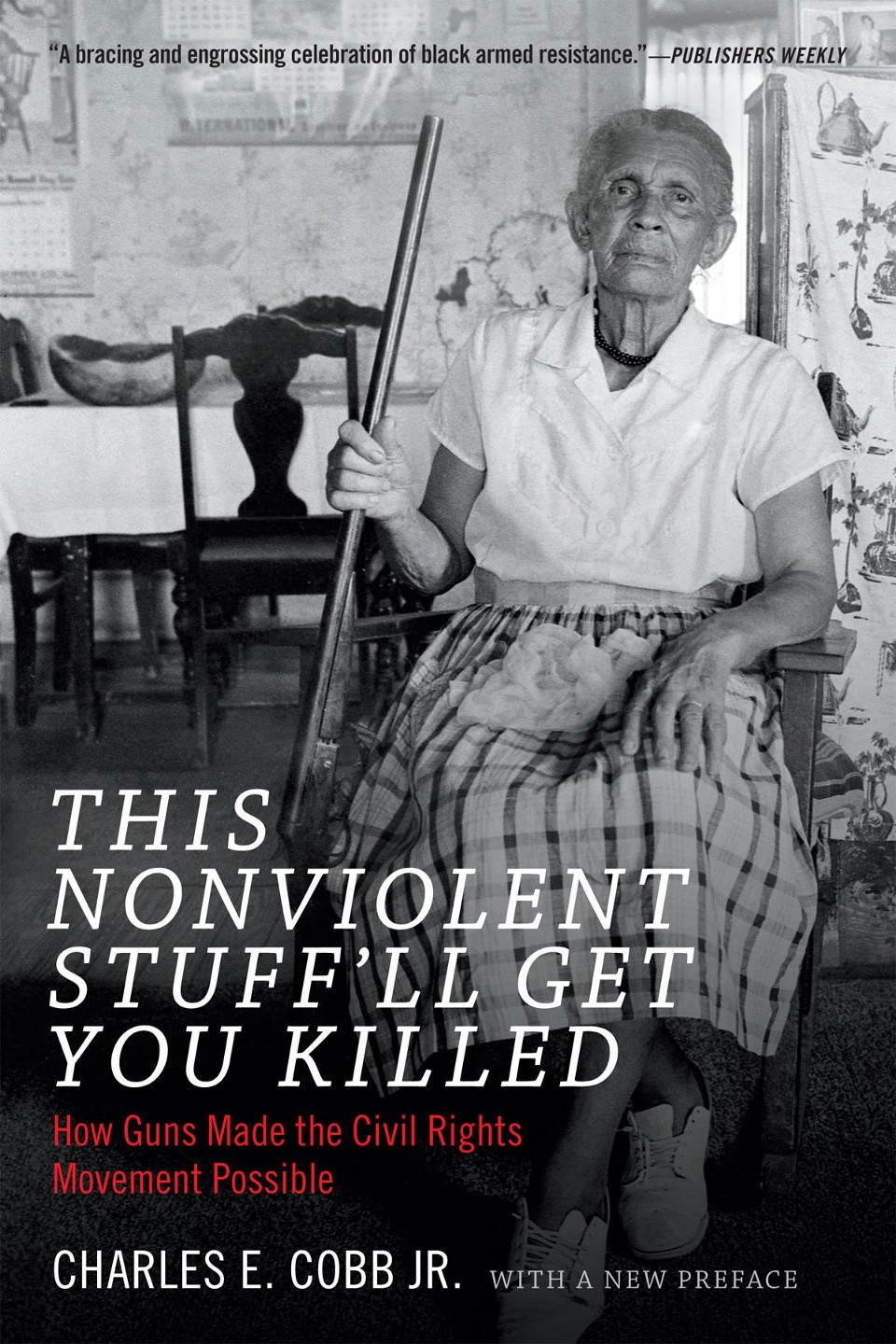

This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible. (Photo: Duke University Press)

“We weren’t considered dignified,” laughs Charles E. Cobb Jr. “They told us the same things, that we were making more enemies than friends, that we were being too disruptive.” Cobb was an organizer with what he calls the “Southern Movement,” working as a Mississippi field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee from 1962 to ’67. I spoke with him about his 2015 book, This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible. “The popular notion is that the Movement was about mass protests in public spaces and charismatic leaders,” he says, “and that’s a problem with the historiography. It was really about grassroots political organizing.” In the book, Cobb writes that accepting the hospitality of families in the South sometimes meant accepting that they would protect your life from white marauders, with violence if necessary. “Non-violence doesn’t work for everything,” Cobb says. “You use self-defense with the Klan.”

Insofar as we can speak of an American Civil Rights Movement that was wholly non-violent, it’s because there was no serious attempt at armed insurrection. According to Cobb, Movement people would bullshit about picking up tactics like the ones rebels were using in the concurrent (armed) battle for independence in Mozambique, but “we were not fighting a liberation struggle,” he says. “We weren’t about to start a guerrilla war to get a cup of coffee.” Malcolm X is often held up as the “violent” foil to King, but even his position was one of self defense. (“Be peaceful, be courteous, obey the law, respect everyone; but if someone puts his hand on you, send him to the cemetery.”) The point is, “non-violence” described a large tactical range. There were avowed pacifists in the Movement, but for the most part the “violent” in “non-violent” referred to “war,” not mere “conflict.” During those hallowed non-violent marches, some people were still throwing rocks at the police. Cobb doesn’t see a contradiction in speaking of a “non-violent assault on a courthouse.”

What unified the Movement was not an ideology of hardcore Christian pacifism, but a determination to make change. Participants diverged in their opinions on tactics and strategies; they argued, debated, switched positions, and sometimes agreed to disagree. Cobb complains — with justification — that white America forgets that black people think. What Cornel West calls the “Santa Clausification” of King serves a useful purpose for the powerful, appropriating the man and thus the Movement for a message of unified national progress. But the history is full of profound and complex disagreement, and we can learn a lot from it. Even while noting her respect for King, playwright and activist Lorraine Hansberry wrote too about embracing “every single means of struggle,” arguing that the Movement had to “harass, debate, petition, give money to court struggles, sit-in, lie-down, strike, boycott, sing hymns, pray on steps, and shoot from their windows when the racists come cruising through their communities.” It’s a good description of a diversity of tactics, and of the Movement in practice.

“Do everything,” is an unobjectionable plan in that all participants get to do what they want, but that’s not what diversity of tactics means in its most effective sense. The former is closer to corporate neoliberal thinking: Burger King’s “Have it your way” but for social change. Some people think we should base our tactics on what’s most palatable to imaginary viewers at home, but Cobb warns against using public approval — especially filtered through the media — as a guide. When he was in Mississippi, public opinion not only didn’t protect Cobb, it was against him. Good tactics, he says, enable activists to dig into communities and organize. Playing to the cameras is appealing given how many there are these days, but that’s only one part of building people’s power. The most important work may not be the most visible, or look the best on the news.

There are good, specific lessons from the Movement for us today, but not the ones Americans are wont to take. “Most of the discussion we have today [about the Civil Rights Movement] is not serious conversation,” Cobb says, “people take the easy way out” by stripping non-violent struggle of its militancy and its basis in grassroots organizing. If today’s activists emulate the Movement we learned about in high school, we’re chasing a mirage. There’s an opportunity to build community power in this country around broadly understood areas of immediate social concern — Cobb suggests taking on police violence, schools that are failing black and brown kids, and unrepresentative local governments (“Get rid of them!”); I would add deportation defense and access to abortion. Building a national spirit of resistance is important (whether by burning a limo, wearing a pussy hat, or burning a limo while wearing a pussy hat). So is supporting the American Civil Liberties Union, I guess, if that’s your thing. But if all of that doesn’t translate into power and organization on a block-to-block level, it will dissolve.

The left is no worse than the rest of America when it comes to reproducing the Santa-claused legend of the Civil Rights Movement, and the false idea that good marches and bad “riots” are the sum total of what resistance looks like. The mainstream media, on the other hand, is worse than average. And if the Resistance plays to the CNN gaze, we’re all headed down a revisionist spiral that, at best, ends in a sappy television movie a decade or two down the line. Stopping Trump — and the destructive forces that animate him — is going to take something closer to fidelity to Cobb and the example he and his comrades set.