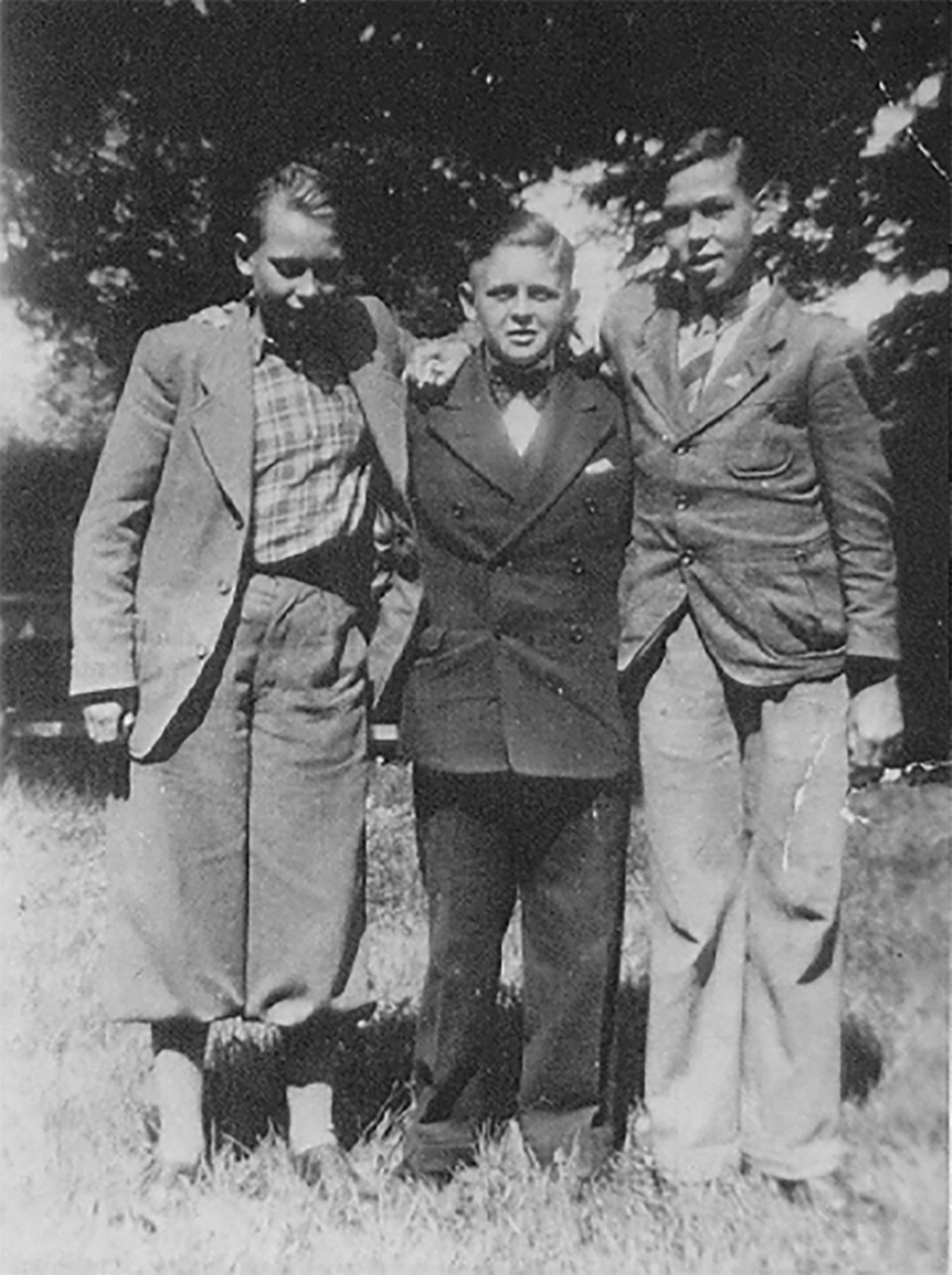

On October 27th, 1942, Helmuth Hübener was beheaded by guillotine at Plötzensee Prison in Berlin. The Nazi regime executed Hübener for treason; he had been surreptitiously listening to enemy radio broadcasts, and he convinced three friends to help him print up and distribute leaflets that contradicted Nazi propaganda. He was caught when he tried to get some information translated into French, in the hopes that he could inspire prisoners of war with good news from the front. Strengthened by his Mormon faith, by all accounts Hübener showed immense bravery in life and as he faced death. Hübener was executed less than three months shy of his 18th birthday; he never denied the charge.

The authorities justified the execution of a minor by arguing Hübener had displayed the political sophistication of an adult, which is both true and false. On the one hand, the Gestapo couldn’t believe that a single 16 year old with a couple friends had been able to successfully carry out so much propaganda work — maintaining a covert radio, listening to BBC reports, typing and distributing flyers.

Hübener did all this because he didn’t like the Nazis, he found anti-Semitism repellant, he hated being forcibly shuttled from the Boy Scouts into the Hitler Youth, and he couldn’t stand the government lying to the people about the war. Like an adult, he looked at his society, applied his critical thinking and investigative faculties, and took a position. But, despite a Nazi court’s ruling, Hübener also behaved a lot like a teenager.

This is a moment of Nazi comparisons for the American people, and I thought of Hübener as I watched high school students across the country walk out of their classes in reaction to the election of Donald Trump. There have been large protests in most major cities in the wake of Trump’s victory, but it has been teenagers who have responded most forcefully. The University of California–Berkeley is famous as the cradle of the radical student movement, but it’s Berkeley High that has distinguished itself in the 21st century. Last year, students walked out when a threatening white supremacist message was left on a computer in the library, and the whole football team kneeled during the National Anthem to join 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick. The day after Trump’s election, 1,500 Berkeley High students left class chanting “He’s not our president.”

When we talk about teenagers in a developmental context, it’s usually with a progressive frame. Sometimes it’s about neurology (they don’t have fully formed frontal lobes, so their judgment is inconsistent) and sometimes psychology (young adults are insecure in their identities, so they’re vulnerable to peer pressure). Teens are understood in their relation to adults — that is, they’re not them yet. They are almost-people whose purpose is to grow up, which is why governments don’t generally execute them, at least not legally.

There is, in fact, no regular adult age. Not only do our conceptions of adulthood change over time — the idea of teenagehood is itself a relatively recent invention — there’s also plenty of variation within all the age cohorts when it comes to qualities like judgment and self-esteem. Using the ages of, say, 35 to 65, as a neutral baseline with which to compare the rest of life betrays a certain prejudice. That may be the age range when people are most likely to publish articles, studies, and books about other people’s judgment, but there’s nothing more human about being 47 than being four or 74.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

In her book Growing Each Other Up: When Our Children Become Our Teachers, Harvard University professor and MacArthur Fellow Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot flips the conventional idea of age as wisdom on its head. The book is about how middle-aged and elderly parents learn from their teenage and adult children, and not just when it comes to figuring out the mechanics of Snapchat. By jumbling up the normal relationship between adults and children, Lawrence-Lightfoot draws the reader’s attention to unconventional ways parents and kids influence one another. For example, a divorced mother draws inspiration from her daughter, who exhibits an openness to the world that seemingly only a young person can. Because this relationship doesn’t conform to our ideas about how families work, it occurs in a social blind spot.

Lawrence-Lightfoot’s observations have a political implication too. “They are living in a world so different from the one in which we grew up,” she writes, “They are becoming people different from any we have ever known.” Parents can tell their kids that they were young once too, but they weren’t young now, and that’s an important difference. Developmental neurology and psychology are important, but brains and minds only ever develop through specific moments in history. We’re all experiencing this world for the first time, and all at once.

The Nazis executed Hübener despite his youth because they said he behaved like an adult, but most adults didn’t resist the Nazi regime, even when they found it distasteful the way Hübener did. To print and distribute resistance flyers upon pain of death is an iffy call: Hübener had no guarantee that his work would do any real good, and the potential costs were total. He did it anyway, and managed to talk his friends into helping him. They used conventionally bad judgment, but now we recognize their heroism for what it was, no matter how developed their lobes.

As President-elect Trump ascends to the White House or 5th Avenue or wherever the seat of government is going to be now, the rest of us are going to need to listen close and learn a lot from teens. We’re conditioned to believe that, despite all their bluster and occasional steps out of line, politicians respect the rules. That has been our experience, or at least how we tend to think of it now. But things change, and an ambitious opportunist (or a cabinet-full) could catch us sleeping.

This cohort of teens, on the other hand, doesn’t have that same experience; their judgment isn’t based on the past 10 to 50 years of American politics. Each additional day of post-election news that I read leads me to believe that this is probably an advantage. There are historical moments when recent experience is more valuable; this looks to be not one of them. Americans opposed to the Trump regime are going to have to expand our political imagination, and a pair of fresh eyes should help.