The biggest surprise of November 8th, 2016, was the fall of three crucial bricks in the great Midwestern “Blue Wall.” Encompassing Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, and Pennsylvania, the Blue Wall was supposed to guarantee electoral victory for Hillary Clinton. But, of course, that’s not how everything played out.

Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, the three states that wound up going for Donald Trump, were former union strongholds that had voted for the Democratic candidate in every single presidential election since 1992 (1988 for Wisconsin). Yet one by one, those states all fell to Trump.

So what happened to the formerly reliably Democratic American heartland?

A new report from the Urban Institute, which lays out some of the challenges and economic anxieties the Great Lakes region has faced in recent years, offers a good hint. The primary culprit behind these heightened tensions? The decline of manufacturing, which accounts for 18 percent of the Great Lakes region’s economy, compared with just 11 percent of the United States’ overall gross domestic product.

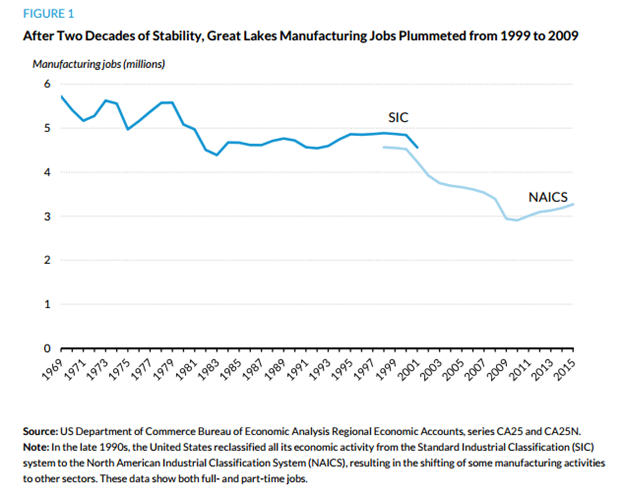

The chart to the left, from the Urban Institute report, illustrates what happened to manufacturing in the Great Lakes region.

Even the economic recovery overseen by President Barack Obama failed to restore the manufacturing sector to its former glory. The region lost almost 1.6 million manufacturing jobs between 2000 and 2010, according to the report—a 35 percent drop. And though manufacturing in the region bounced back from 2010 to 2015, adding some 350,000 jobs, the end result is still a net loss of 1.2 million manufacturing jobs.

Some states in the region were hit especially hard. Michigan, for example, lost 45 percent of its manufacturing jobs between 1998 and 2010.

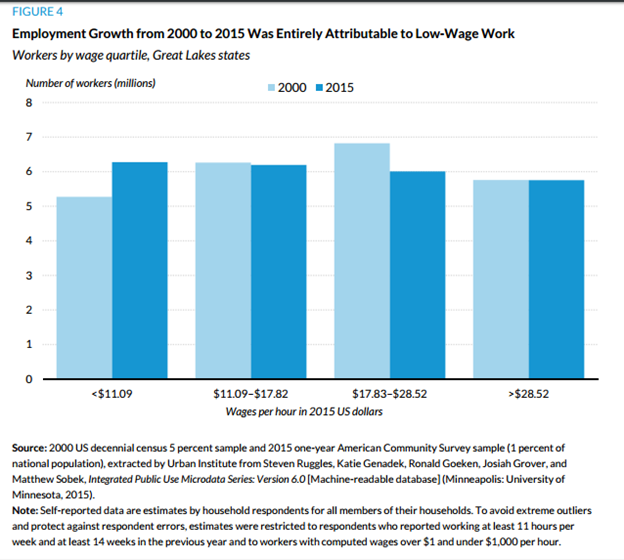

While there are some new jobs in the Great Lakes region—primarily in service-oriented industries like health care—these gigs come with a major caveat: They don’t pay much. As the chart to the left illustrates, virtually all of the employment growth in the Great Lakes region between 2000 and 2015 occurred in the bottom quintile, jobs paying less than $11 per hour.

“The economic composition in the Great Lakes is different from the rest of the U.S.,” says Rolf Pendall, one of the report’s authors. “It doesn’t have finance or tech. To the extent that our economy continues to boom or bust based on those industries, or to the extent that income growth and job growth comes from those industries … those aren’t the kind of industries that are anchored in the Great Lakes.”

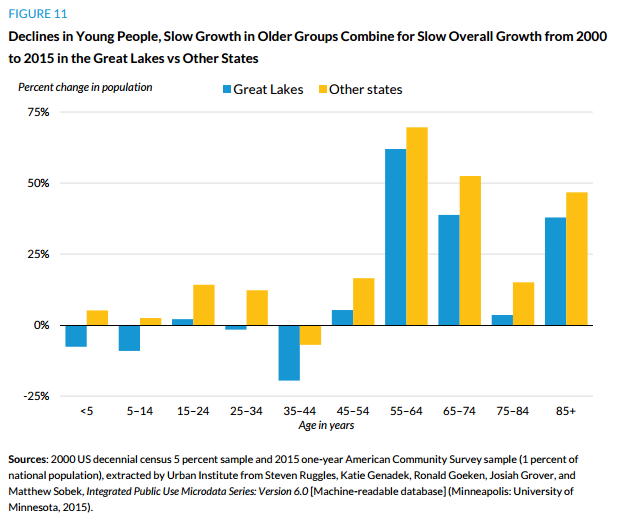

Much of this narrative is familiar, but there’s another big challenge facing the region, one that is both separate from the economy and inevitably intertwined with it: The American Heartland is aging. Birth rates are down, mortality rates are edging up (thanks in no small part to the opioid crisis), and the region is losing young people.

As shown in the chart to the left, which compares the demographic composition of the Great Lakes region to that of the country at large, at some point (perhaps in the late 2020s) the population of the region might actually start to decline, if current demographic trends aren’t reversed. Pendall says these demographic challenges highlight the importance of investing in the region’s young people. He believes policies like paid family leave, affordable childcare or early childhood education, and good public schools are crucial to retaining the region’s young people and families, and ensuring that the region still has a well-educated workforce in a few decades.

“This region represents one-sixth of the population of the United States; it’s the cradle of manufacturing in the United States,” Pendall says. “We need to invest in the kids in this region. It’s about seeing each of these people as being potentially somebody who could earn 60, 70, 100 thousand a year if they get the right kinds of opportunities from the time they’re born.”

Pendall is skeptical the skinny budget that the Trump administration proposed last week would help the region—these states are neither hotbeds of federal defense spending nor are they close enough to the proposed border wall to benefit from any increased spending on that project. On the other hand, the skinny budget proposes dramatic cuts to programs that the region does rely on, including the Community Development Block Grant program and Great Lakes clean-up program overseen by the Environmental Protection Agency.

“I think [this budget] is going to hurt the Great Lakes,” he says. “The idea that this is a budget that’s going to rebuild the Great Lakes and reduce the disparity between the East Coast and this region is just not believable.”