Ahmed Mohamed wanted to be an inventor. He ended up in handcuffs.

The simple facts of the case surrounding the 14-year-old student’s arrest are infuriating. Mohamed, a ninth-grader at Irving MacArthur High School in Irving, Texas, loved to tinker with electronics. One evening, he built a clock from circuit boards and wiring, which he stashed in a pencil case. On Tuesday, he showed his creation to his teachers. His engineering instructor praised the design; the English teacher thought it was a bomb. Mohamed was handcuffed by police officers and interrogated for hours. No charges were filed.

The outrage over the unnecessary arrest quickly went viral. This incident—a Muslim boy with a distinctive name and a pencil box full of wiring—seems like a case of clear-cut Islamophobia. The details of his time in police custody are alarming to say the least:

They led Ahmed into a room where four other police officers waited. He said an officer he’d never seen before leaned back in his chair and remarked: “Yup. That’s who I thought it was.”

Ahmed felt suddenly conscious of his brown skin and his name — one of the most common in the Muslim religion. But the police kept him busy with questions.

The bell rang at least twice, he said, while the officers searched his belongings and questioned his intentions. The principal threatened to expel him if he didn’t make a written statement, he said.

“They were like, ‘So you tried to make a bomb?'” Ahmed said.

“I told them no, I was trying to make a clock.”

“He said, ‘It looks like a movie bomb to me.'”

But apart from the glare of anti-Muslim anxiety (Irving mayor Beth Van Duyne made headlines earlier this year when she melted down over alleged “sharia courts” coming to her town), the school’s opaque response to media inquiries and concerned parents is telling: “While we do not have any threats to our school community, we want you to be aware that the Irving Police Department responded to a suspicious-looking item on campus yesterday,” wrote Principal Daniel Cummings in a letter to parents. “This is a good time to remind your child how important it is to immediately report any suspicious items and/or suspicious behavior they observe to any school employee so we can address it right away. We will always take necessary precautions to protect our students.”

If this boilerplate response sounds all too familiar, it’s because police and school administrators use it all the time after arresting students for completely moronic reasons. A 12-year-old girl was taken into custody in Texas for spraying herself with perfume. Another student in Texas was arrested for throwing paper airplanes in class. In New Mexico, a 13-year-old boy was arrested for burping in class; another student was ordered to strip down to his underwear with five teachers watching because he had $200 on his person. A 12-year-old girl in New York was arrested for doodling on her desk, while an eight-year-old boy in Massachusetts was administered a psychological evaluation because he drew a picture of Jesus in class. And let’s not forget the Oklahoma math teacher who made a citizen’s arrest on a student for possessing a permanent marker, which apparently came in violation of “an obscure city ordinance.”

Broken windows has come to the American schoolyard.

While Ahmed’s incident comes with a sheen of Islamophobia (to wit: this list of students who brought homemade clocks to school and weren’t arrested), it also speaks to a broader question: When did we start criminalizing innocent childhood antics? Schools have been trending toward increased security over the last few decades. According to the National Institute of School Psychologists, 68 percent of students between the ages of 12 and 18 said in 2009 that they had security guards or police officers in their schools. Seventy percent said their schools had surveillance cameras; 11 percent had to deal with a metal detector.

It’s not just the presence of police and other security forces: While schoolyards have evolved from “playgrounds” into “high-security environments” over the past few decades, research shows that teachers and school administrators have embraced stricter models of discipline and punishments, resulting in students “feeling powerless as a result of the manner in which their schools enforce rules and hand down punishments,” according to San Diego State University sociologist Nicole Bracy. In Ahmed’s native Texas, the Guardian reported that, in 2010 alone, police “gave close to 300,000 ‘Class C misdemeanors’ tickets to children as young as six in Texas for offenses in and out of school, which result in fines, community service and even prison time.” It seems broken windows has come to the American schoolyard.

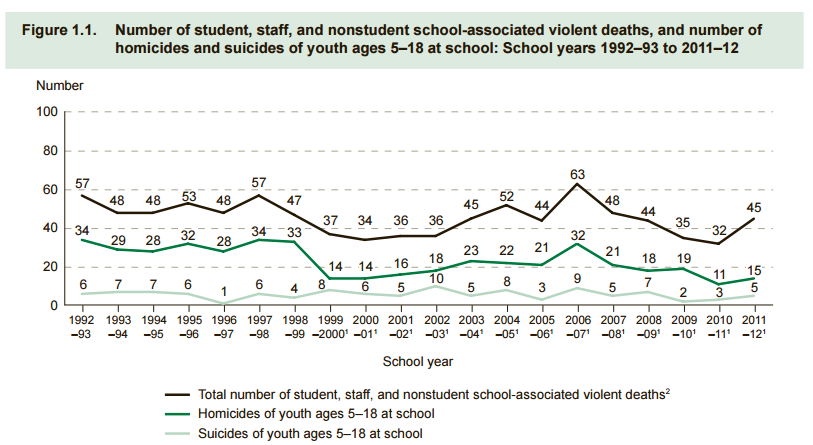

But has it worked? Each year, the Departments of Justice and Education publish the Indicators of School Crime and Safety report to examine the prevalence of crime and violence in America’s institutions of learning—and from the looks of latest data, schools have never been safer. According to the 2014 ISCS report, homicides of students between the ages of five and 18 at school have steadily declined from a peak of 34 in the 1992–93 school year to 15 from 2011–12, before the Sandy Hook massacre in Newtown, Connecticut. If the goal had been to prevent violence in America’s school—whether mass shootings or other interpersonal conflicts—the drop in fatalities would suggest that heightened safety measures are indeed working.

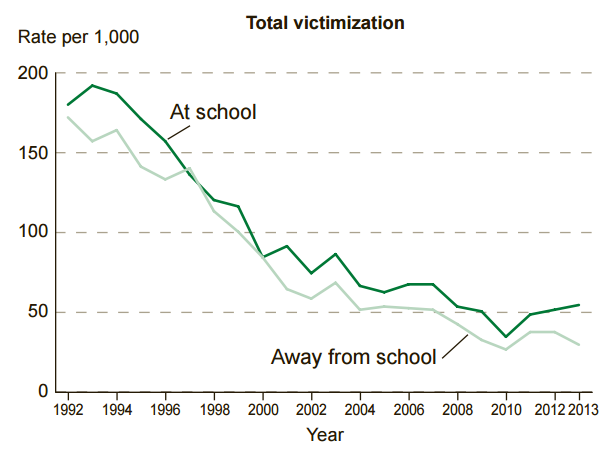

While outright deaths at school fell, other forms of victimization—threats and theft, mainly—fluctuated. In 2013, Students between the ages of 12 and 18 were more likely to be violently victimized at school than they were anywhere else (2013 violent victimization rates were 37 per 1,000 students at school, and 15 per 1,000 students away from school) But, despite this, overall violent victimization rates both at and away from school have steadily declined since 1993; even a slight increase from 2010 to 2013 is still below the peak two decades ago. But then again, this measures up right alongside a drop in overall violent crime rate. Was it security measures or an overall decline in crime at play here?

Even fights and violent weapon possessions are down. Between 1993 and 2003, the percentage of students who reported being in a fistfight fell from 42 percent to 25 percent. Even better, the percentage of students who reported carrying a weapon at school fell from 12 percent in 1993 to five percent in 2013.

But the most interesting part of the ISCS report? While adults may flip out over a “suspicious” science project or a belch, students actually feel safer at school. The percentage of students who reported being afraid of attack or harm at school or on the way to and from school decreased from 12 percent in 1995 to three percent in 2013, and the percentage of students who reported being afraid of attack or harm away from school decreased from six percent in 1999 to three percent in 2013. Despite recent warnings by the FBI that mass shootings are on the rise, students don’t seem as perturbed as their teachers do.

It’s hard to claim, based on the ISCS data, that increased security measures have failed at preventing school violence. But Mohamed Ahmed captures the negative externality of increased school security. It seems almost inevitable that students should face the misapplication of school security measures by educators and law enforcement officials. Some legal scholars have argued that, not unlike increased security in the aftermath of 9/11, the criminalization of the schoolyard has serious ramifications for students’ Fourth Amendment rights. “Zero tolerance started out as a term that was used in combating drug trafficking and it became a term that is now used widely when you’re referring to some very punitive school discipline measures,” Deborah Fowler, deputy director of legal rights group Texas Appleseed, told the Guardian in 2012. “Those two policy worlds became conflated with each other. What we see often is a real overreaction to behavior that others would generally think of as just childish misbehavior rather than law breaking.”

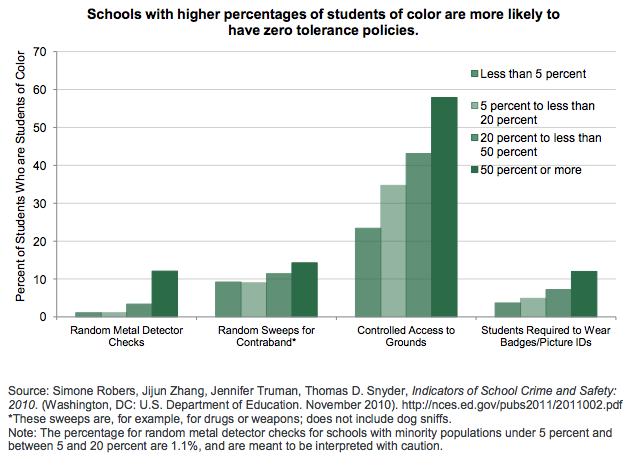

There’s also a problem of simply derailing an education: How many students have their futures marred by an inexplicable arrest on their permanent record? “The increase in the presence of law enforcement in schools, especially in the form of school resource officers (SROs) has coincided with increases in referrals to the justice system, especially for minor offenses like disorderly conduct,” observed Justice Policy Institute senior researcher Amanda Petteruti in a 2011 report on the rise of police in schools. “This is causing lasting harm to youth, as arrests and referrals to the juvenile justice system disrupt the educational process and can lead to suspension, expulsion, or other alienation from school. All of these negative effects set youth on a track to drop out of school and put them at greater risk of becoming involved in the justice system later on.” In a time when the Justice Department has compared the school-to-prison pipeline to modern-day racial segregation, this should give school administrators pause. After all, the JPI report shows that zero-tolerance policies disproportionately affect students of color:

There are also more immediate consequences. The Guardian reports that the assorted fines, often around $500, doled out for absurd violations of school codes of conduct, can be “crippling” for low-income families—not unlike the bail bond system that’s been used to keep innocent people in prison for days at a time. “Some parents and students ignore the financial penalty, but that can have consequences years down the road,” the Guardian reports. “Schoolchildren with outstanding fines are regularly jailed in an adult prison for non-payment once they turn 17. Stumping up the fine is not an end to the offending student’s problems either. A class-C misdemeanor is a criminal offense.”It’s impossible to argue that arrest of Ahmed Mohamed doesn’t reflect a very real strain of Islamophobia that flows through post-9/11 American society—especially given the circumstances of his interrogation by police—but that’s not all his story represents. It’s a collision of post-9/11 Islamophobia and post-Columbine anxiety over school safety, expressed through the draconian criminalization of childhood experimentation and hijinks rather than, say, better checks on handguns. Sure, these systems appear to work in discouraging violence in schools (United States v. Lopez lives!), but at what costs to innocent students and their potential futures? And why is there no system of accountability to hold school administrators and law enforcement officials accountable for their misapplication of the law?

Since news of his arrest vent viral, #IStandWithAhmed has become a symbol of outrage over the budding engineer’s unjust treatment. But perhaps more than many other solidarity tags, we can relate to this one more. Anyone who’s gone to school in the U.S. in the past two decades, public or private, has likely had some brush with the paranoia and anxiety that seems to have overtaken reason in the case of school security. If you don’t like things like this, you can change it: After all, all local politics begins with the school board.