Americans have a low opinion of Congress. Less than 10 percent of voters think that Congress is doing a good job. But their own representative … not so bad. A third of us think that our own rep deserves re-election, according to a Rasmussen poll. Even that is low. Until recently, a majority of people approved of their own representative while disapproving of Congress in general. It’s been the same with crime. People feel safer in their own neighborhoods than elsewhere, even when those other neighborhoods have less crime.

Race relations, too, are bad … elsewhere. In the last year, the percentage of Americans saying that race relations in the country are “bad” doubled (roughly from 30 percent to 60 percent). That’s understandable given the media coverage of Ferguson, Missouri, and other conflicts centered on race. But people take a far more sanguine view of things in their own community. Eighty percent rate local race relations as “good,” and that number has remained unchanged throughout this century.

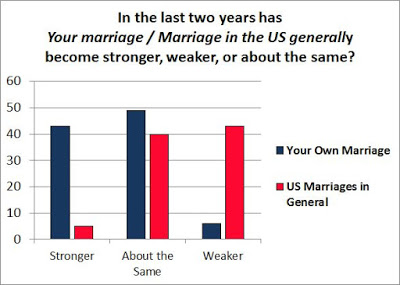

It’s not surprising, then, that the problem with marriage in the United States turns out to be about other people’s marriages. A recent survey asked people about the direction of their own marriage and marriage in the U.S. generally.

Only a handful of people (five percent) see marriage generally as getting stronger. More than eight times that number say that their own marriages have strengthened. The results for “weaker” are just the reverse. Only six percent say that their own marriage has weakened, but 43 percent see marriage in the U.S. as losing ground.

Why the “elsewhere effect”? One suspect is the media bias toward trouble. Good news is no news. News editors don’t give us many stories about good race relations, or about the 25-year drop in crime, or about the decrease in divorce. Instead, we get crime and conflict and a variety of other problems. Add to this the perpetual political campaign with opposition candidates tirelessly telling us what’s wrong. Given this balance of information, we can easily picture the larger society as a world in decline, a perilous world so different from the one we walk through every day.

At first glance, people seeing their own relationships as good and others’ relationships as more strained seems like the opposite of the pluralistic ignorance on college campuses. There, students often believe that things are better elsewhere, or at least better for other students. They think that most other students are having more sex, partying more heartily, and generally having a better time than they are themselves. But whether we see others as having fun or more problems, the cause of the discrepancy is the same—the information we have. We know our own lives firsthand. We know about those generalized others mostly from the stories we hear. And the people—whether news editors or students on campus—select the stories that are interesting, not those that are typical.

This story originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “The Elsewhere Effect.”