QUANTICO, VIRGINIA — More than 30 years ago, the Federal Bureau of Investigation launched a revolutionary computer system in a bomb shelter two floors beneath the cafeteria of its national academy. Dubbed the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program, or ViCAP, it was a database designed to help catch the nation’s most violent offenders by linking together unsolved crimes. A serial rapist wielding a favorite knife in one attack might be identified when he used the same knife elsewhere. The system was rooted in the belief that some criminals’ methods were unique enough to serve as a kind of behavioral DNA—allowing identification based on how a person acted, rather than their genetic make-up.

Equally as important was the idea that local law enforcement agencies needed a way to better communicate with each other. Savvy killers had attacked in different jurisdictions to exploit gaping holes in police cooperation. ViCAP’s “implementation could mean the prevention of countless murders and the prompt apprehension of violent criminals,” the late Senator Arlen Specter wrote in a letter to the Justice Department endorsing the program’s creation.

In the years since ViCAP was first conceived, data-mining has grown vastly more sophisticated, and computing power has become cheaper and more readily available. Corporations can link the food you purchase, the clothes you buy, and the websites you browse. The FBI can parse your emails, cell phone records, and airline itineraries. In a world where everything is measured, data is ubiquitous—from the number of pieces of candy that a Marine hands out on patrol in Kandahar, to your heart rate as you walk up the stairs at work.

That’s what’s striking about ViCAP today: the paucity of information it contains. Only about 1,400 police agencies in the United States, out of roughly 18,000, participate in the system. The database receives reports from far less than one percent of the violent crimes committed annually. It’s not even clear how many crimes the database has helped solve. The FBI does not release any figures. A review in the 1990s found it had linked only 33 crimes in 12 years.

Canadian authorities built on the original ViCAP framework to develop a modern and sophisticated system capable of identifying patterns and linking crimes. It has proven particularly successful at analyzing sexual-assault cases. But three decades and an estimated $30 million later, the FBI’s system remains stuck in the past, the John Henry of data mining. ViCAP was supposed to revolutionize American law enforcement. That revolution never came.

Few law enforcement officials dispute the potential of a system like ViCAP to help solve crimes. But the FBI has never delivered on its promise. In an agency with an $8.2 billion yearly budget, ViCAP receives around $800,000 a year to keep the system going. The ViCAP program has a staff of 12. Travel and training have been cut back in recent years. Last year, the program provided analytical assistance to local cops just 220 times. As a result, the program has done little to close the gap that prompted Congress to create it. Police agencies still don’t talk to each other on many occasions. Killers and rapists continue to escape arrest by exploiting that weakness. “The need is vital,” said Ritchie Martinez, the former president of the International Association of Law Enforcement Intelligence Analysts. “But ViCAP is not filling it.”

Local cops say the system is confusing and cumbersome. Entering a single case into the database can take an hour and hits—where an unsolved crime is connected to a prior incident—are rare. False positives are common. Many also said the FBI does little to teach cops how to use the system. Training has dropped from a high of about 5,500 officers in 2012 to 1,200 last year.

“We don’t really use ViCAP,” said Jeff Jensen, a criminal analyst for the Phoenix Police Department with 15 years of experience. “It really is quite a chore.”

The FBI has contributed to the confusion by misrepresenting the system. On its website, the FBI says cases in its database are “continually compared” for matches as new cases are entered. But in an interview, program officials said that does not happen. “We have plans for that in the future,” said Nathan Graham, a crime analyst for the program. The agency said it would update the information on its website.

The agency’s indifference to the database is particularly noteworthy at a time when emerging research suggests that such a tool could be especially useful in rape investigations.

For years, politicians and women’s advocates have focused on testing the DNA evidence in rape kits, which are administered to sexual assault victims after an attack. Such evidence can be compared against a nationwide database of DNA samples to find possible suspects. Backlogs at police departments across the country have left tens of thousands of kits untested.

But DNA is collected in only about half of rape cases, according to recent studies. A nationwide clearinghouse of the unique behaviors, methods, or marks of rapists could help solve those cases lacking genetic evidence, criminal experts said. Other research has shown that rapists are far more likely than killers to be serial offenders. Different studies have found that between one-fourth to two-thirds of rapists have committed multiple sexual assaults. Only about one percent of murderers are considered serial killers.

Studies have questioned the assumptions behind behavioral analysis tools like ViCAP. Violent criminals don’t always commit attacks the same way and different analysts can have remarkably different interpretations on whether crimes are linked. And a system that looks for criminal suspects on the basis of how a person acts is bound to raise alarms about Orwellian overreach. But many cops say any help is welcome in the difficult task of solving crimes like rape. A recent investigation by ProPublica and the New Orleans Advocate found that police in four states repeatedly missed chances to arrest the former NFL football star and convicted serial rapist Darren Sharper after failing to contact each other. “We’re always looking for tools,” said Joanne Archambault, the director of End Violence Against Women International, one of the leading police training organizations for the investigation of sexual assaults. “I just don’t think ViCAP was ever promoted enough as being one of them.”

The U.S. need only look north for an example of how such a system can play an important role in solving crimes. Not long after ViCAP was developed in the U.S., Canadian law enforcement officials used it as a model to build their own tool, known as the Violent Criminal Linkage Analysis System, or ViCLAS. Today, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police maintains a database containing more than 500,000 criminal case profiles. The agency credits it with linking together some 7,000 unsolved crimes since 1995—though not all of those linkages resulted in an arrest. If the FBI collected information as consistently as the Mounties, its database would contain more than 4.4 million cases, based on the greater U.S. population.

Instead, the FBI has about 89,000 cases on file.

Over the years, Canada has poured funding and staff into its program, resulting in a powerful analytical tool, said Sergeant Tony Lawlor, a senior ViCLAS analyst. One critical difference: in the U.S., reporting to the system is largely voluntary. In Canada, legislators have made it mandatory. Cops on the street still grumble about the system, which resembles the American version in the time and effort to complete. But “it has information which assists police officers, which is catching bad guys,” Lawlor said. “When police realize there’s a value associated with it, they use it.”

The ViCAP program eventually emerged from the fallout shelter where it began. It set up shop in an unmarked two-story brick office building in a Virginia business park surrounded by a printer’s shop, a dental practice, and a Baptist church.

In a lengthy interview there, program officials offered a PowerPoint presentation with case studies of three serial killers who were captured in the past eight years with the help of the ViCAP program. They called the system “successful.”

“We do as good a job as we possibly can given our resources and limitations,” said Timothy Burke, a white-haired, 29-year agency veteran who is the program manager for ViCAP. “As with anything, we could always do better.”

Pierce Brooks was the father of the system.

A legendary cop, he had a square jaw, high forehead, and dead serious eyes. During 20 years with the Los Angeles Police Department, he helped send 10 men to death row. He inspired the fictional Sergeant Joe Friday character in Dragnet. And he became famous for tracking down a pair of cop killers, a hunt chronicled in Joseph Wambaugh’s 1973 non-fiction bestseller, The Onion Field. “Brooks’ imagination was admired, but his thoroughness was legend,” Wambaugh wrote.

In the late 1950s, Brooks was investigating two murder cases. In each, a female model had been raped, slain, and then trussed in rope in a manner that suggested skill with binding. Brooks intuited that the killer might commit other murders. For the next year, he leafed through out-of-town newspapers at a local library. When he read a story about a man arrested while trying to use rope to kidnap a woman, Brooks put the cases together. The man, Harvey Glatman, was sentenced to death, and executed a year later.

The experience convinced Brooks that serial killers often had “signatures” — distinct ways of acting that could help identify them much like a fingerprint. An early adopter of data-driven policing, Brooks realized that a computer database could be populated with details of unsolved murder cases from across the country, then searched for behavioral matches.

After Brooks spent years lobbying for such a system, Congress took interest. In July 1983, Brooks told a rapt Senate Judiciary Committee audience about serial killer Ted Bundy, who confessed to killing 30 women in seven states. The ViCAP system could have prevented many of those deaths, he said. “ViCAP, when implemented, would preclude the age-old, but still continuing problem of critically important information being missed, overlooked, or delayed when several police agencies, hundreds or even thousands of miles apart, are involved,” Brooks said in a written statement.

By the end of the hearing, Brooks had a letter from the committee requesting $1 million for the program. Although the program was endorsed by then-FBI director William Webster, agency managers weren’t particularly thrilled with the new idea.

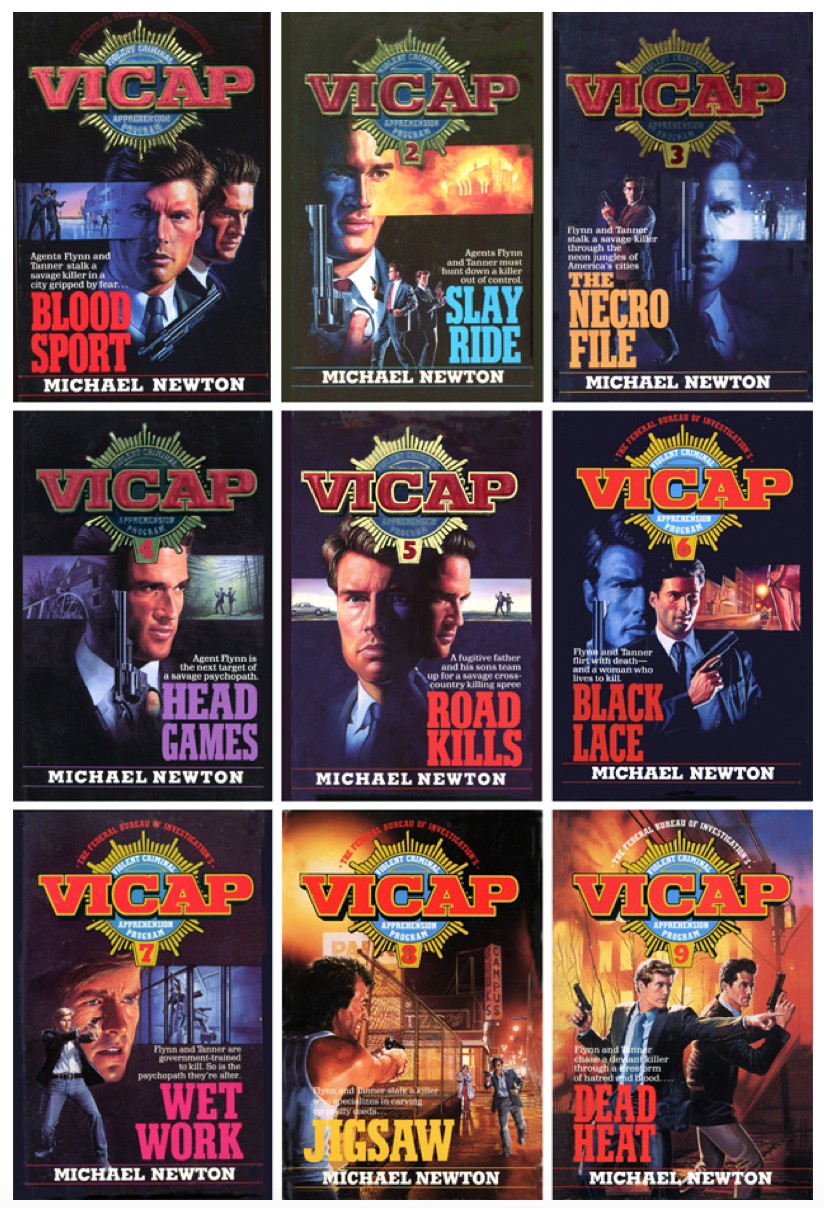

The FBI grafted ViCAP into a new operation—the Behavioral Analysis Unit. The profilers, as they were known, were later made famous by Thomas Harris’ The Silence of the Lambs as brainy crime fighters who combined street smarts and psychology to nab the worst criminals. But at the time, the unproven unit was seen as a kind of skunk works. The FBI housed it in the former fallout shelter—“ten times deeper than dead people” as one agent later recalled. It was a warren of rooms, dark and dank. Others referred to the oddball collection of psychologists, cops, and administrators as “rejects of the FBI” or the “leper colony,” according to Into the Minds of Madmen, a non-fiction account of the unit. Still, the new program captured the imagination of some. Murder mystery author Michael Newton penned a series of novels which, while not quite bestsellers, featured the heroic exploits of two ViCAP agents “accustomed to the grisly face of death and grueling hours on a job that has no end.”

Brooks was the first manager for the ViCAP program. The agency purchased what was then the “Cadillac” of computers—a VAX 11/785 nicknamed the “Superstar.” It filled up much of the room in the basement headquarters and had 512KB of memory. (An average household computer today has about 4,000 times more memory.) Brooks was “ecstatic” when the system finally came online on May 29, 1985, according to the account. His enthusiasm was not to last.

To get information into the database, local cops and deputies had to fill out by hand a form with 189 questions. The booklet was then sent to Quantico, where analysts hand-coded the information into the computer. It was a laborious process that flummoxed even Brooks. He had a hard time filling out the booklet, according to one account—as did officers in the field. Only a few hundred cases a year were being entered.

Enter Patricia Cornwell, the bestselling crime author, famous for her novels featuring Dr. Kay Scarpetta, medical examiner. In the early 1990s, she visited the subterranean unit during a tour of the academy. She recalled being distinctly unimpressed. An analyst told her that ViCAP didn’t contain much information. The police weren’t sending in many cases.

“I remember walking into a room at the FBI and there was one PC on a desk,” said Cornwell, who had once worked as a computer analyst. “That was ViCAP.” A senior FBI official had told Cornwell that the academy, of which ViCAP was a small part, was in a financial crunch. She contacted Utah Senator Orrin Hatch, a friend, and told him of the academy’s troubles. In 1993, Hatch shepherded a measure through Congress to put more money into the academy—and ViCAP.

As the money made its way to the bomb shelter, the FBI conducted a “business review.” It found that local cops were sending the agency only three to seven percent of homicides nationwide. The minuscule staff—about 10 people—could not even handle that load, and was not entering the cases on a timely basis. Cops on the street saw the system as a “black hole,” according to Cold Case Homicide, a criminal investigation handbook.

The FBI decided to kill the program. They picked Art Meister to be the hit man.

Meister spent much of his career at the FBI busting organized crime, beginning at the New Jersey field office. He rose through the ranks to supervise a national squad of more than 30 agents, investigating mob activities at home and overseas. He had no real experience with behavioral analysis or databases. But he did have an analytical approach that his superiors admired. They gave him instructions: “If it doesn’t work, do away with it. Kill it,” recalled Meister, now a security consultant with the Halle Barry Group.

Meister heard plenty of complaints. At one conference of police officers from across the country, a cop pulled Meister aside to talk about the program. “I’ve used it and all it gives me is bullshit leads,” the officer told him. “The general perception was by and large that the program didn’t work,” Meister said.

But instead of killing ViCAP, Meister became the system’s unlikely champion. Even with its small staff, the program was connecting far-flung law-enforcement agencies. The 189 questions had been slimmed to 95—making it easier to fill out the form. Meister used the new funding from Hatch’s bill to reach out to 10 large jurisdictions to persuade them to install terminals that could connect with the database. By 1997, the system was receiving 1,500 or so cases per year—a record, though still a fraction of the violent crimes committed.

Meister saw the potential for the database to help solve sexual-assault crimes. He pushed the development of new questions specifically for sexual-assault cases. They weren’t added to the system until after his departure in 2001. “I felt it would really pay off dividends,” Meister said. “There are a lot more serial rapists than serial killers.”

But he found it difficult to make headway. Top officials showed no real interest in the program. After all, it was designed to help local law enforcement, not the agency. Meister called ViCAP “the furthest planet from the sun”—the last in line to get funds from the FBI. His efforts to improve it “were met with skepticism and bureaucratic politics. That’s what drove me nuts,” he said.

By the time he left, the program was muddling along. “ViCAP never got the support that it needs and deserves.” Meister said. “It’s unfortunate.”

On July 13, 2007, at four in the morning, a 15-year-old girl was sleeping in her bedroom in Chelmsford, a former factory town in northeastern Massachusetts bisected by Interstate 495.

She was startled awake when a man dressed in black with a ninja mask pressed his hand against her face. He placed a knife to her throat and told her “If you make any noise, I’ll fucking kill you.”

The girl screamed, rousing her mother and father. The parents rushed in, fighting with the man until they subdued him. Adam Leroy Lane, a truck driver from North Carolina, was arrested. In his truck, Massachusetts police found knives, cord, and a DVD of Hunting Humans, a 2002 horror film.

Analysts for ViCAP, which has a special initiative to track killings along the nation’s highways, determined that the Massachusetts attack was similar to an earlier murder that had been committed in New Jersey. Acting on the tip, New Jersey state police detectives interviewed Lane in his jail cell. Lane confessed to killing Monica Massaro, a 38-year-old woman, in her home in the town of Bloomsbury—just a few blocks off Interstate 78. Lane, dubbed the Highway Killer, was connected via DNA samples to a killing and a violent attack in Pennsylvania; both women lived near interstates. Lane is now serving a life sentence in Pennsylvania.

New Jersey State Police Detective Geoff Noble said his case had been stalled. But once ViCAP connected Noble to Massachusetts police officers, they provided him a receipt that placed Lane at the truck stop in the small town where Massaro was killed. And when Noble confronted Lane, the killer started talking. Under a state attorney general’s directive, all New Jersey law enforcement agencies are supposed to report serial crimes to ViCAP. “The information provided by ViCAP was absolutely critical,” Noble said. “Without ViCAP, that case may have not ever been solved.”

FBI officials said the case, one of three success stories provided to ProPublica, showed the critical role of the database. (The other two: The case of Israel Keyes, a murderer who committed suicide after his arrest in Alaska in 2012 and has been linked to 11 killings; and that of Bruce Mendenhall, a trucker now serving a life sentence in Tennessee who was linked to the murder of four women in 2007.) “Given what we have, it’s a very successful program,” Burke said.

But in a dozen interviews with current and former police investigators and analysts across the country, most said they had not heard of ViCAP, or had seen little benefit from using it. Among sex-crimes detectives, none reported having been rewarded with a result from the system. “I’m not sending stuff off to ViCAP because I don’t even know what that is,” said Sergeant Peter Mahuna of the Portland, Oregon, Police Department. “I have never used ViCAP,” said Sergeant Elizabeth Donegan of Austin, Texas. “We’re not trained on it. I don’t know what it entails or whether it would be useful for us.”

Even Joanne Archambault, the director of the police training organization who sees the potential of ViCAP, didn’t use it when she ran the sex-crimes unit at the San Diego Police Department: “In all the years I worked these crimes, we never submitted information to ViCAP,” she said. “As a sex-crime supervisor, we invested time in effort that had a payout.”

Local authorities’ skepticism is reflected in the FBI’s statistics. In 2013, police submitted 240 cases involving sexual assault to the system. The FBI recorded 79,770 forcible rapes that year. Local agencies entered information on 232 homicides. The FBI recorded 14,196 murders.

“It’s disappointing and embarrassing,” said Greg Cooper, a retired FBI agent who directed the ViCAP unit before becoming the police chief in Provo, Utah. “The FBI has not adequately marketed the program and its services. And local law enforcement has not been committed to participating.”

Not all rapes or murders involved serial offenders, of course. But with ViCAP receiving information on only about 0.5 percent of such violent crimes, it struggles to identify those that do.

“Cops don’t want to do more paperwork,” said Jim Markey, a former Phoenix police detective and now a security consultant. “Anytime you ask for voluntary compliance, it won’t be a priority. It’s not going to happen.”

But at some agencies where ViCAP has been incorporated into policing, commanders have become staunch defenders of its utility. Major J.R. Burton, the commander of special investigations for the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office in Tampa, Florida, said detectives at his agency are mandated to enter information on violent crimes into the database. “I love ViCAP,” said Burton, who served on a board of local law enforcement officials that advises the FBI on the system. “There’s many cases where you don’t have DNA. How do you link them together?”

Burton said he understood the frustration that other police experience when they get no results back from the system. When pressed, Burton could not cite any investigations in his jurisdiction that had benefited from the database. But he said the time and effort to use the system was worth it. “It allows you to communicate across the nation, whether serial homicide or serial rapist,” Burton said. “That’s awesome in my book.”

FBI officials said they had taken steps to address complaints. In July 2008, the program made the database accessible via the Web. Police can now enter their own searches, without having to rely on an FBI analyst, through any computer with an Internet connection. The program has also whittled down the number of questions. Graham says he tells police that it should take only about 30 minutes to enter the details of a case. “I tell them if they can fill out their taxes, they can fill out the ViCAP form,” Graham said.

In November 1980, children began vanishing across Canada.

Christine Weller, 12, was found dead by a river in British Columbia. A year later, Daryn Johnsrude, 16, was found bludgeoned to death. In July 1981, six children were killed in a month, ages six to 18. They were found strangled and beaten to death.

The killer: Clifford Olson, a career criminal, who eluded capture in part because the different jurisdictions where he committed his crimes had never communicated.

The murders prompted Canadian police officials to create a system to track and identify serial killers. After an initial effort failed, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police sent investigators to study the ViCAP program. They returned troubled by some aspects. The FBI system was not being used by many police agencies. Nor did it track sexual assaults. The Mounties decided to improve on the U.S. system by developing their own behavioral crime analysis tool—ViCLAS.

The ViCLAS system has three advantages over its American cousin: people, money, and a legal mandate. More than a hundred officers and analysts work for the system, spread across the country. It’s funded at a reported cost of $14 million to $15 million per year. The most important development was that over the years, local legislative bodies passed laws making entry mandatory. All Canadian law enforcement agencies now file reports to the system.

The agency also greatly expanded the list of crimes that can be entered. Any crime that is “behaviorally rich”—usually an incident involving a criminal and a victim—can be entered into the database. It also created stringent quality control. A Canadian analyst who uncovers a link between crimes must submit the findings to a panel for review. Only then can the case be released to local agencies—reducing the chances for bad leads.

Today, Canada’s system has been repeatedly endorsed by senior police officials as an important tool in tracking down killers and rapists. The agency routinely publishes newsletters filled with stories about crimes that the system helped to solve. One study called ViCLAS the “gold standard” of such systems worldwide. The Mounties now license ViCLAS for an annual fee to police forces in Belgium, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

The volume of information submitted has made the all the difference, Lawlor said. The system works when enough agencies enter cases to generate results. But agencies are reluctant to enter cases until they see results. “It’s a catch-22 situation,” Lawlor said. “If nothing goes in, then nothing can go out.”

When Burke, ViCAP’s program manager, speaks at national law enforcement conferences, he asks how many people in the audience have heard of his program. Typically only about one-half to two-thirds of the hands go up. A smaller percentage say they actually use it.

“We don’t have a club to force them to sign up with us,” Burke said.

The program’s main goal now is to ensure that the 100 largest police agencies in the country are enrolled. About 80 are. The agency continues to slowly develop its software. Training occurs monthly to encourage more participation.

The FBI doesn’t see the need for major changes to ViCAP, Burke explained. “It’s still supportive,” Burke said. “It’s still viable.”

This post originally appeared on ProPublica as “The FBI Built a Database That Can Catch Rapists — Almost Nobody Uses It” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.