In the aftermath of the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa Volcano, the Javan rhino found a refuge in an increasingly overcrowded island. But living in the shadow of a volcano comes with some risks.

By Tom Peeters

This picture, taken on November 16th, 2013 shows a member of the Javan Rhino Study and Conservation Area looking at a footprint of a rhino in Ujung Kulon National Park in Indonesia’s Banten province. For people seeking a glimpse of the Javan rhino — revered in local folklore as Abah Gede, or the Great Father — such small signs are likely to be the closest they get. (Photo: Adek Berry/AFP/Getty Images)

Take a piece of land the size of Louisiana, place 45 active volcanoes on it and pack it full of 140 million people. The scenario of the newest action thriller in which Tom Cruise has to rescue humanity? No, it’s the daily reality of the Indonesian island of Java.

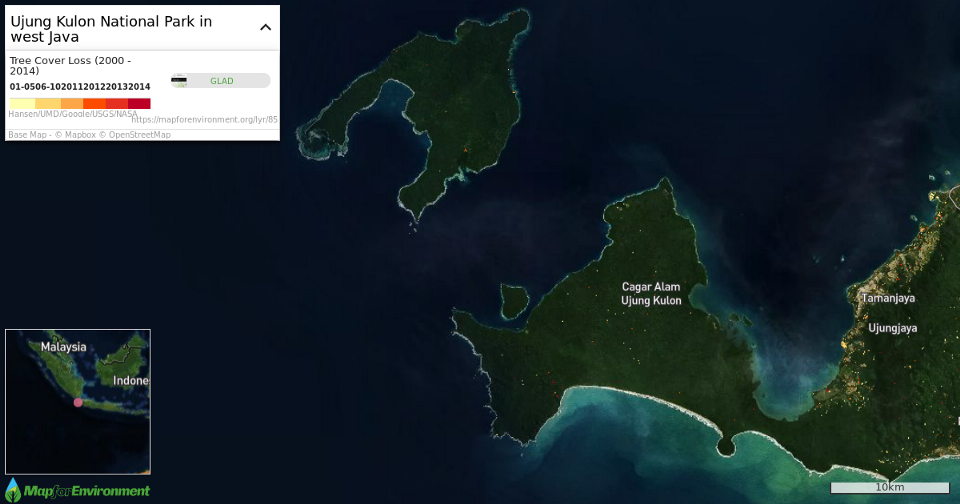

Here, in one of the most densely populated areas on Earth, the Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus) fights for its survival. Listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the 60 or so remaining Javan rhinos all roam the forests of Ujung Kulon, a national park in the westernmost tail of the island. The Javan rhino is living on the edge, literally and figuratively.

Ujung Kulon National Park sits on the southwestern tip of Java. (Map: Map For Environment)

This is the Ring of Fire, among the most volcanically active places on Earth. Millions of people nonetheless live near volcanoes that could wipe them out in a second. The reason is simple: volcanoes are not only occasional bringers of death but also constant givers of life. They kill people with their lava, pyroclastic, and mud flows, but reward them by feeding their land volcanic ash, full of fertile minerals.

The last of the Javan rhinos are living close to such a ticking time bomb as well. Anak Krakatau, the child of Krakatau, is a volcanic island ever ready for action. One large eruption could terminate the worldwide population of Javan rhinos forever. In terms of species conservation, it’s like keeping your best china in the middle of a football field.

Java’s volcanoes have left their mark on the Javan rhinoceros’ fate in many ways.

They gave the island its immense fertility, rich enough to feed the fast-growing population. But while Java’s human population has exploded since the early 19th century, its rhino population took a nosedive. Wherever rice paddies appeared, lowland rainforest disappeared. Man drove the rhino to the corners of Java—out of its natural habitat, toward higher grounds and isolated peninsulas, as far as possible from civilization without actually dropping into the Indian Ocean.

One of those final redoubts is Ujung Kulon, across a narrow strait from what is now one of the most famous volcanoes in history. Here, the powers that rendered Java fertile enough to support tens of millions of people gave the Javan rhino a little push in the armored back.

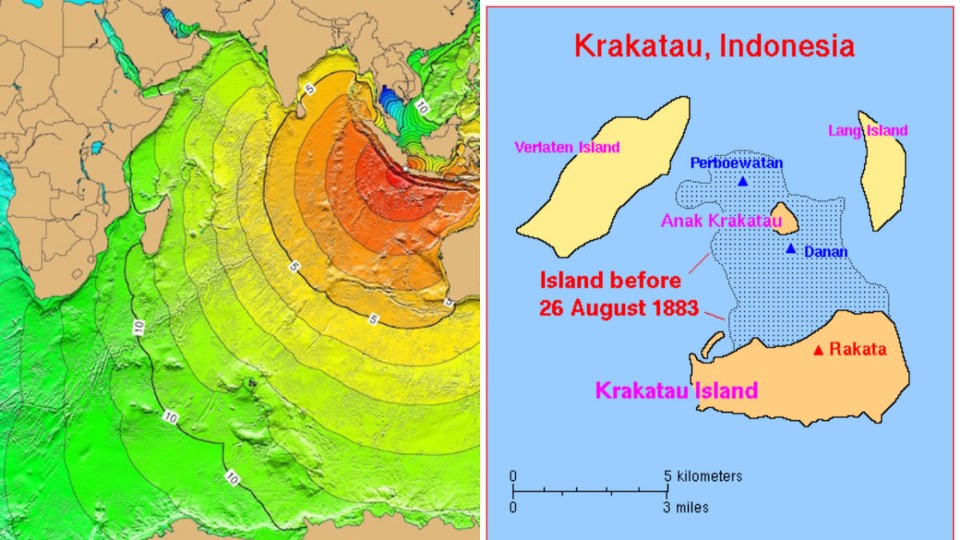

The year is 1883. Late August, the volcanic island Krakatau has had enough. With merciless violence it blows itself up with 10,000 times the force of the nuclear bomb later dropped on Hiroshima.

The explosion snapped the eardrums of sailors on ships 40 miles (64 kilometers) away. Three thousand miles from ground zero, people looked up from their morning coffees.

Hundred-foot-high tsunamis flooded the coasts of Ujung Kulon, leaving a wasteland behind. As the land began to recover, Javan rhinos — under heavy threat elsewhere on the island — recolonized. Humans never returned in large numbers, so, to this day, Ujung Kulon remains a safe haven for the rhino.

Krakatoa’s 1883 eruption caused massive devastation creating tsunamis (mapped on the left) that killed around 36,000 people. (Images: Courtesy of NOAA and USGS/Wikimedia Commons)

The volcano has thrown the rhino a lifeline; its presence also hangs over the animal’s head like the sword of Damocles. After Krakatau blew its top, its successor began to grow steadily below sea level. Anak Krakatau lifted its head above the water in the 1920s and is by now an oversized teenager. Already exceeding 1,000 feet (300 meters) and gaining 15 more each year, the child volcano will continue to grow until it reaches a size at which it will follow its predecessor’s example.

Low-lying Ujung Kulon can easily be flooded. Such an event would be catastrophic for any kind of wildlife, but it’s extra disastrous when it comes to the last specimens of a species.

During a workshop in 2015, experts tried to quantify the danger more concretely. They analyzed the viability of the existing rhino population in Ujung Kulon with a simulation model. Thus, they probed the risk of extinction in various scenarios. According to a study, a natural disaster theoretically halves a population of Javan rhinos once every century. The simulation model calculated, however, that, in only 3.6 percent of the cases, such a disaster would also lead to a complete extinction of that population.

Nineteenth-century illustration of a Javanese rhino. The species is so elusive few photographs exist. (Photo: Courtesy of the Biodiversity Heritage Library)

This means that, even with the threat ever present, the volcano is not the biggest concern of environmental groups fighting for the survival of the Javan rhino. “The present population can probably recover from a natural disaster, even though that would take time,” says Susie Ellis, executive director of the International Rhino Foundation. However, she notes, even if part of the park’s rhino population managed to survive an eruption, it could have a serious impact on the viability of the surviving rhinos. “The smaller the population gets, whether because of a disaster or any other reason, the greater the risk of inbreeding,” she says.

Moreover, any big natural disaster would come on top of the existing problems. The invasive Arenga palm (Arenga pinnata) overgrows a lot of the favorite food of the rhino. Poachers can once again find their way to Ujung Kulon, which has been deprived of such villains for years.

These problems, at least, have some potential solutions: Arenga palm can be cut, no matter how big the bureaucratic mess to do so. Poachers can be kept out with extensive security. But if Anak Krakatau decides to roar, there’s nothing anyone can do about it. It highlights the enormous vulnerability of the Javan rhino.

“It’s never a good idea to keep all eggs in the one basket,” Ellis says. “Everyone is convinced of the need for a second site, so we can translocate a subset of the current population.” This way, numbers can be raised, the gene pool extended, and the future of the Javan rhino secured. Especially since Ujung Kulon has its limits.

The animal eats a lot of plants in one day and needs enough space to romp. Not many large lowland rainforests remain in Southeast Asia, let alone in cramped Java. Remember: that was, in the first place, one reason for the rhinoceros’ disappearance.

“The search for a second site is excruciatingly slow,” Ellis says. “The location should provide sufficient and proper food, and has to be securable and large enough. And we have to find the right balance: We have to translocate enough animals to start a new population without ruining the chances of the rhinos remaining in Ujung Kulon.” With such a small population, there is no room for error, Ellis says.

“I’m personally not sure if there exists such a place in Java that meets all the requirements, an area big enough for a wild, self-regulating population. Maybe it needs to happen in (semi-)captivity and we’ll have to manage a lot more than we’d hoped for,” she says. “Some experts suggest to look toward Sumatra, because the island has yet more forests and is within the historical range of the Javan rhino. It’s an option, as long as the animal does not compete with the Sumatran rhino. But it’s unlikely that the government will give the green light quickly.”

Until then, fingers crossed that Anak Krakatau stays quiet for a while longer.

This story originally appeared at the website of global conservation news service Mongabay.com. Get updates on their stories delivered to your inbox, or follow @Mongabay on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.