A new report from the Hamilton Project highlights the lingering effects of the Great Recession on food insecurity in America.

By Dwyer Gunn

(Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

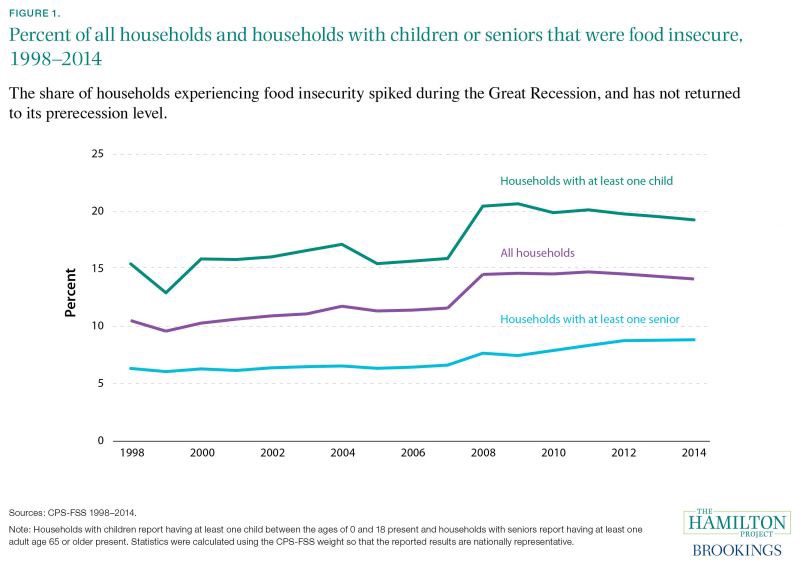

Last week, the Hamilton Project, a policy initiative spinoff of the Brookings Institution, hosted a conversation with United States’ Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack on food insecurity. The event was accompanied by the Hamilton Project’s new report on the topic, which makes for mostly grim reading. The report finds that, though food insecurity, which increased sharply during the Great Recession, has declined, it still hasn’t returned to pre-recession levels. In fact, in states with particularly high levels of food insecurity, almost 30 percent of children live in a food-insecure household.

“From 1998 to 2007 an average of 15.7 percent of households with children, 10.8 percent of households overall, and 6 percent of households with seniors were food insecure,” the report concludes. “The average from 2008 to 2014 was roughly 4 percentage points higher for households overall and for households with children, and about 2 percentage points higher for households with seniors.”

This graph from the report illustrates food insecurity trends since 1998:

(Chart: The Hamilton Project)

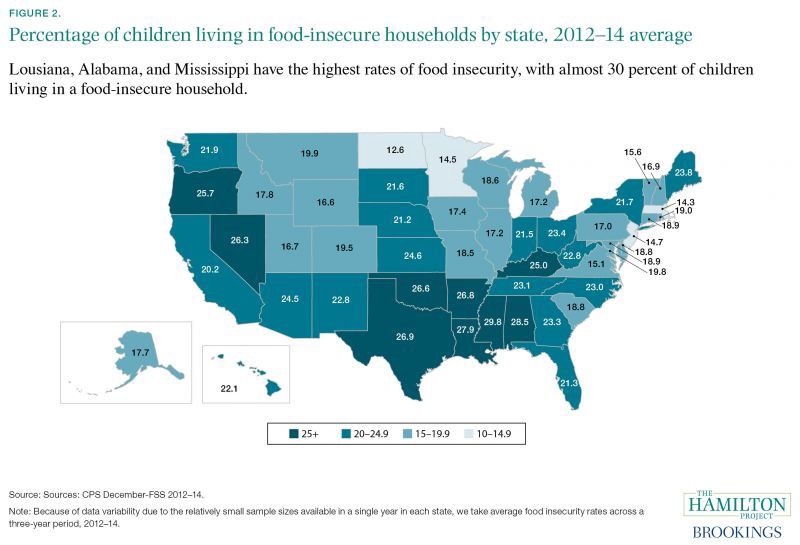

There’s considerable state-by-state variation in food insecurity levels across the country, demonstrating once again that geography matters if you’re poor. The Hamilton Project has created an interesting interactive map that illustrates state-by-state food insecurity over time:

(Chart: The Hamilton Project)

Some of this variation is no doubt due to local economic conditions — it’s not a coincidence that the states with the highest levels of food insecurity (Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi) are also some of the poorest states in the country. But state-level policy decisions around the social safety net can also play a crucial role in food insecurity.

Here’s what Vilsack had to say about some states’ approach to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and whether SNAP should be eliminated in favor of a block grant (as House Speaker Paul Ryan has proposed):

I’m leery about block grants, just simply because I haven’t seen governors step up.

I alluded earlier, when we came in in 2009, there were states where a little over 50 percent of eligible people were actually receiving SNAP because that particular governor, that particular administration, did not care enough to make sure that people knew about these benefits, did not care enough to make sure that their bureaucracy was getting information out in languages that people could understand, did not care enough to simplify the process, so I’m skeptical.

The Obama administration has successfully increased overall SNAP participation levels to 85 percent, but Vilsack’s comments illustrate how seemingly minor local political decisions around SNAP education and outreach can affect enrollment in a program that effectively reduces food insecurity.

The report also highlights how stagnating wages and the anemic nature of the economic recovery have affected food insecurity. While many still associate food insecurity with deep poverty, it’s not just very poor families dealing with food insecurity: Eighty-five percent of food-insecure households with children are headed by a working adult, and one-third of food insecure families report incomes over 200 percent of the poverty line (over $48,000 a year for a family of four); another third have incomes between 100 and 200 percent of the poverty line.

“It has to do with all the various things we’re worried about, this economic distress,” says Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, director of the Hamilton Project and one of the report’s authors. “People are dealing with stagnant wages and increasing costs in other areas — housing and transportation — so it’s not surprising that we’re seeing people having a hard time stretching their budgets to cover their food needs. But it means we need to have a serious conversation about what to do about people who are above the reach of the safety net.”

Food insecurity and hunger have long-lasting consequences, particularly for children. Hunger impairs emotional and intellectual development. It is also associated with mental and physical health problems later in life. Researchers have demonstrated that hungry kids don’t perform as well academically, and are more likely to have disciplinary issues.

“Hungry kids aren’t going to be learning as well as they should. They’re not going to be as well-prepared for the competitive economy that they’re going to grow up in,” Vilsack said at the event. “The reality is that families that are struggling with food insecurity have to make very difficult choices, and it impacts the future of kids, and it impacts the future of this country.”

The economic forces that have battered lower- and middle-income Americans are complex, and there’s no silver bullet solution to the challenges that have left so many Americans vulnerable to hunger and food insecurity. There are, however, evidence-based solutions to food insecurity: SNAP, supplemental summer nutrition benefits, and school meal programs, among others. It’s time, as Schanzenbach says, for a serious conversation about the growing number of working and middle-class Americans who are struggling to feed their families.

||