The homemade sign bore a simple message: “Plant trees not bombs,” written in red and black marker, in English and Pashto, and held by a man standing in his field at the base of mountains near Jalalabad, Afghanistan.

The man had a second sign, this one at the entrance to his distilleries where he turns his bitter oranges and roses into essential oils for use in perfumes: “No weapons beyond this point,” it read, a reminder that outside the walls there is still the Taliban. And, not too far away, ISIS.

The man is Abdullah Arsala, an Afghan businessman who has defied the Taliban by denying their expectations to grow poppies for opium — the poppies that contribute to his country’s drug epidemic and that supply roughly 80 percent of the world’s heroin. In 1994, Arsala emigrated to the United States, where he attended University of California–Davis to study biochemistry. When he could no longer afford the tuition, he dropped out and worked on organic farms where he became enamored with agriculture. By 2002, he was back in his country, where he reclaimed his family’s land, and set about growing something beautiful.

In 2009, Arsala was contacted by Barb Stegemann, who saw Arsala as her chance to fulfill a promise. Stegemann’s best friend Trevor Greene, a Canadian military captain, had been injured in a Taliban axe attack while on a peaceful mission to bring clean water to villages. As her friend lay in a coma, Stegemann vowed that she would continue his mission to help the people of Afghanistan.

In Arsala, Stegemann saw someone already at work in Afghanistan providing opportunities to his struggling community. By supporting Arsala’s business — purchasing the essential oils he was creating directly from him — she could keep her promise to Captain Greene.

It’s a story told in a new documentary, Perfume War, which follows Stegemann’s and Greene’s paths — hers as she tries to find a way to honor her promise and help those in conflict zones, his as he recovers from his injuries. It was directed by another friend, Michael Melsky, a classmate from their university days. Perfume War, Melsky says, “is a story about fighting war without conventional weapons, combatting injustice and inhumanity with ideas.” Melsky was originally planning to have Arsala do some filming himself, given a Canadian travel ban to Afghanistan during production, but, in a poignant twist, the Taliban prevented Arsala from sending his video footage back. As Melsky tells it, that created new challenges but also a chance to tell a different kind of story. “Abdullah is a very key character,” he says. “We brought him to life through his stories, through his e-mails, through his photos.” That challenge underscores the special relationship between Stegemann and Arsala who, though they’ve never met, have forged an entrepreneurial and emotional connection that’s transforming lives.

There were plenty of high-paying military jobs available in the early 2000s to an Afghan who spoke English and had computer skills — but Arsala resisted. Instead, he held fast to his dream of farming his land, to which he feels a deep connection, and which has been in his family for centuries. Each day he would head into the mountains where he collected different herbs and flowers to distill in pressure cookers, experimenting to create a high-quality oil he could sell on the international market, even though Afghan’s oils were “a drop in the ocean,” Arsala says.

His friends and family thought he was crazy. The farmers growing poppy were making good money. Poppy grows easily and is a perennial, whereas the rose and the bitter orange he chose to grow would take years to begin producing flowers he could use. He held firm. The beauty of producing essential oils is that, as with the drug trade, a small amount is worth a lot of money (though still roughly 20 percent less than high-quality opium). But with druglords taking the bulk of the profit from poppy, farmers often don’t get their money on time, Arsala says; sometimes the crop is seized. He’s proud of having resisted the lures of the poppy trade. “The economy I have created is not related to war,” he says. “I look at it as a very noble way of farming.” What’s more, Arsala’s choice to grow orange and rose instead of poppy doesn’t go against Islamic law, an important consideration to a devout Muslim.

Cultivating oils in Afghanistan, though, is not without risks — particularly the way Arsala went about it.

For one thing, the Taliban were not pleased to have someone challenging their sway in the community. For another, Arsala’s own finances were stretched, as he extended loans to area farmers to help them also move from growing poppies to planting roses. “When these farmers were alternating from poppy to rose, they had to eat something,” he says. “It takes rose three years to flower.” Arsala insists on paying his approximately 1,500 farmers fairly, citing wages higher than those being paid in neighboring countries. “I believe in socially responsible business,” he says. And when it came time to hire harvesters for his crops, he made sure that at least a quarter of them were women.

Sleepless nights were the norm. Arsala was overextended from not only his own business but also from subsidizing so many others. He abandoned the 25-kilogram pressure cookers he was using on stove burners for industrial-size 3,000-kilogram distilleries, which the Taliban would occasionally knock over. Electricity was unreliable and expensive.

And though Arsala was producing the oil, Afghanistan presented unique challenges in finding buyers. “The cost is quite high to send samples, and we don’t have laboratories to send my soil samples. There’s a lot of testing required and a lot of analysis and we don’t have the infrastructure in the country so I have to send everything out of the country to test,” he says. Arsala was beginning to have doubts.

Then Barb Stegemann came knocking.

Stegemann, a single mom with her own public relations company, read about Arsala in a 2008 NPR story. Arsala’s defiant plan cemented her own: She would create a perfume so she could buy his oils. As she says in Perfume War: “If Abdullah was selling saffron, I’d be the spice lady.”

“When she got in touch with me, I was a small producer,” Arsala says. Stegemann, who borrowed off her credit card after her bank refused her a loan, spent 2,000 Canadian dollars to purchase one cup of the bitter orange oil to produce her first perfume, Afghanistan Orange Blossom. “At that time, it was like a drop in the ocean but it gave me a little vision,” Arsala says. “We will have buyers.… We are going on the right path.”

Six weeks later, Stegemann was selling the fragrance from her garage and had already broken even. She purchased Arsala’s rose oil and created a second scent, Noble Rose of Afghanistan.

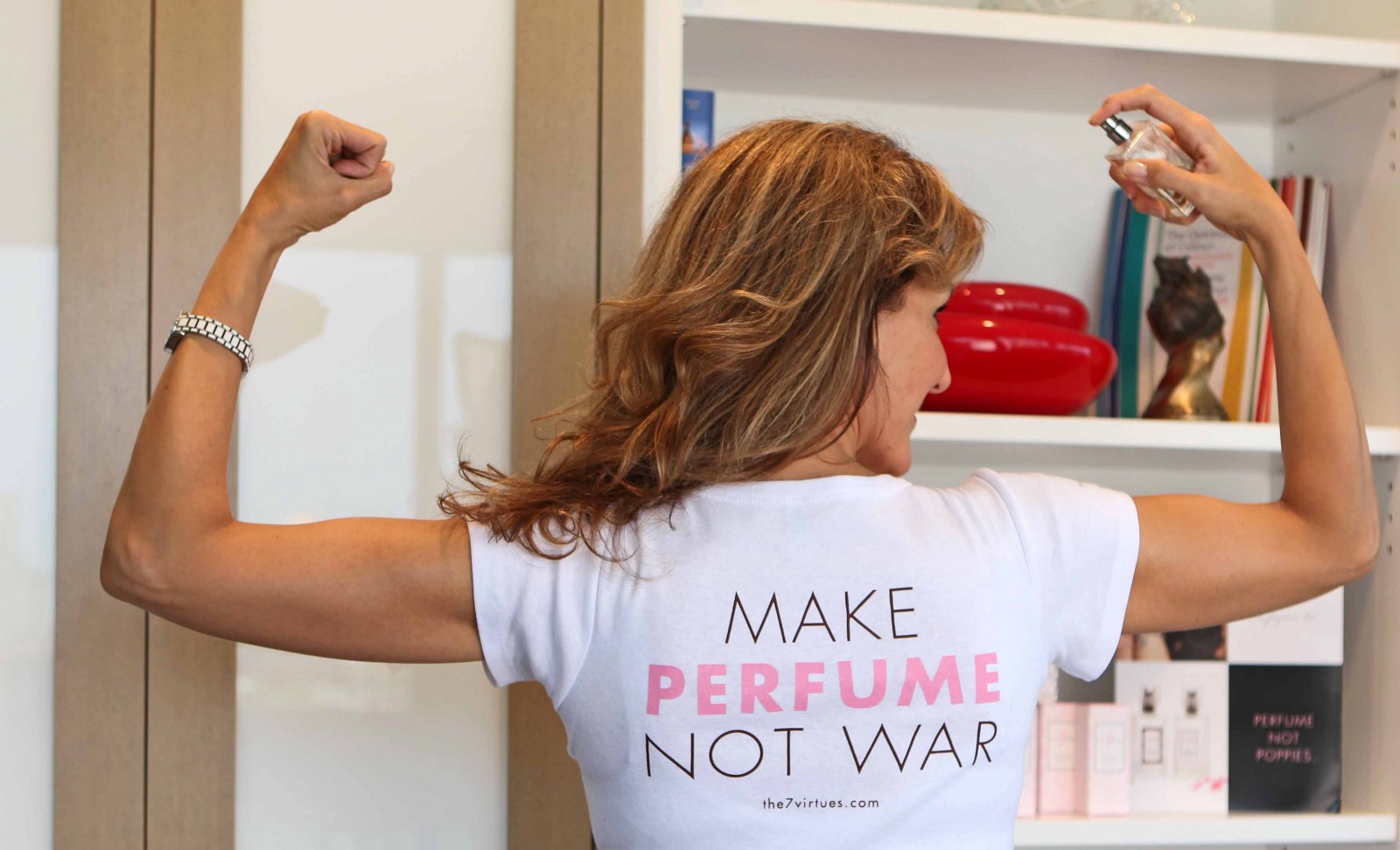

As Stegemann’s business grew — she placed her brand, The 7 Virtues, in major department stores in Canada, the U.S., the United Kingdom, Germany, and Austria — it introduced Arsala’s product to international buyers. Separately, he’s been negotiating with a large European perfume company for a promising deal.

Arsala still struggles in a country that’s become less stable since U.S. troops began pulling out. “It’s much more dangerous,” Stegemann says. Arsala has lost some employees who’ve been killed by the Taliban. Yet he remains steadfast, his no weapons allowed sign promising a sanctuary from violence to those, like him, committed to producing something of beauty and dignity.

He’s heartened by watching boys and girls walk to the school his family helped build and which is named after his father, who was killed during the Soviet-Afghan war.

Stegemann calls Arsala a spiritual leader and businessman, “funny and cool and respected.”

“I have gray hair,” he says with a laugh. “I’ve had threats and different issues but I don’t worry much about that because I grew up in war and I’m not afraid of being put off my mission.”

Stegemann has never met Arsala in person but says their bond is strong. “Inshallah,” she writes in her e-mails to him, God willing. “Shalom,” he replies. They feel bound to each other in their mission and in their faith, “soul mates,” as Stegemann puts it. It doesn’t seem to matter that they’ve never met face to face. A planned meeting in the U.K. where a perfumer promised to teach them the tricks of the trade fell through for Arsala who determined it wasn’t safe to leave his business and his employees.

“It’s a modern story,” she says, noting our wired world has made their business relationship and their friendship easy. “Here’s a female half-Jew with a Muslim man cutting through all the clutter and being filled with love — and that’s all that matters,” Stegemann says.

Stegemann is proud of Perfume War, a film about extraordinary friendships: between Stegemann and Greene, who continues to surprise doctors and inspire other brain-injured patients with his progress; between Stegemann and Arsala, united in a mission to harness something beautiful that can empower farmers and transform a country. It’s about friends, says Michael Melsky, “who are trying to change the world.”