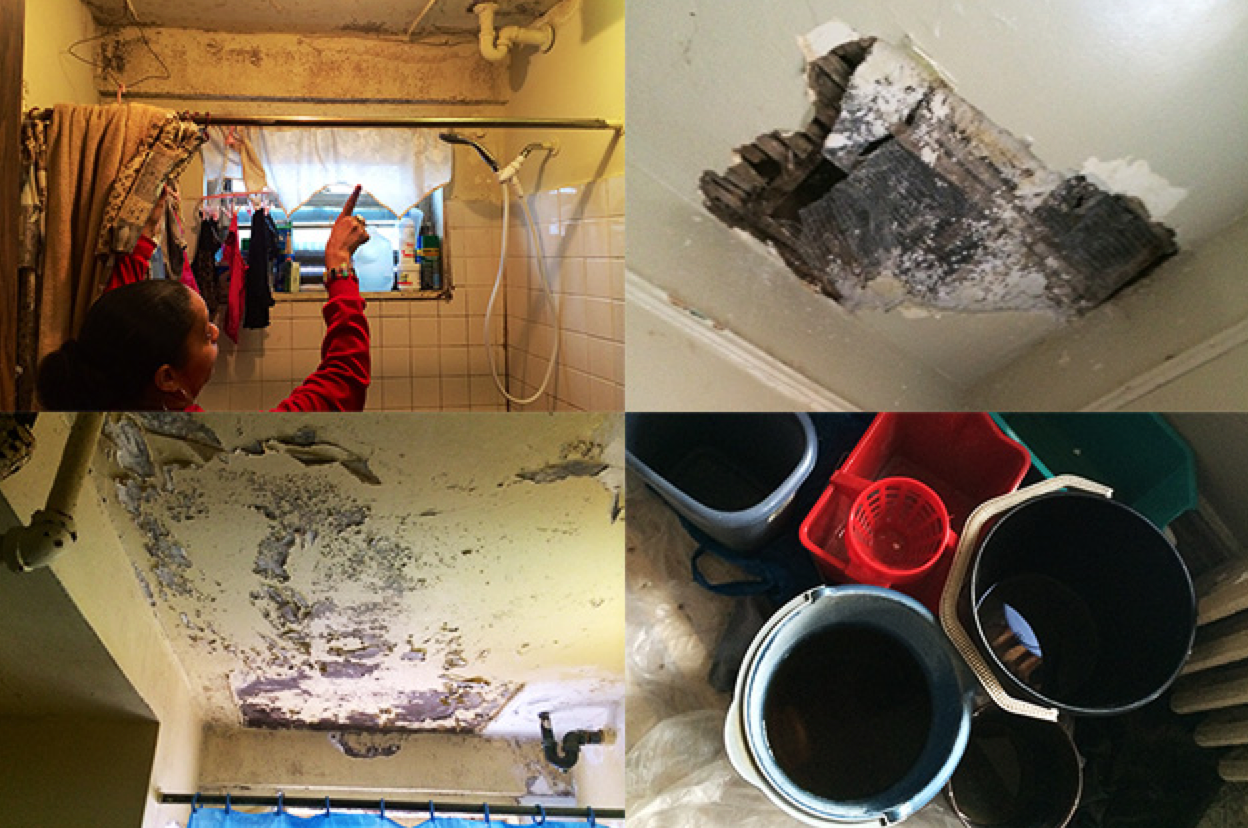

At Maria Santana’s public housing apartment on New York’s Upper West Side, dirty, black water has periodically poured in from the walls, from the pipes, from the radiator. She says the problems started two years ago.

“It’s so much water, it looks like it’s raining in here. I am scared,” Santana said. She has placed buckets throughout her apartment. Her couch is covered in plastic to keep it from getting wet.

Santana, 60, says she lives in fear that dripping water will come down on the electrical outlets and start a fire. She’s taped and covered some of her outlets with plastic as a precaution.

Her red folder is a testament to how many times she’s tried to get help from her landlord, the New York City Housing Authority. Inside, scrawled in Spanish and broken English, are long lists of ticket numbers and notes from her calls to NYCHA’s hotline. Workers would come to the apartment sometimes and make small fixes, she said, but they never actually solved the problems.

“It was so bad. So bad. The walls in the bathroom, they bubbled like bubble gum.” They were so soggy that the bathroom sink fell off the wall more than once.

“They gave me ticket, ticket, ticket, ticket, ticket,” Santana said, paging through her papers. “Over here too, ticket, ticket, ticket, ticket. They just give you tickets. But they don’t do nothing.” (NYCHA’s media office declined ProPublica’s requests for updates on specific tickets, directing us instead to make formal records requests.)

Santana, who’s been in public housing for more than two decades, has seen the decline of the NYCHA, which was once considered one of the nation’s best-run housing authorities. The agency, which is the country’s largest public housing authority and home to more than 400,000 tenants, has suffered from a decade of underfunding and aging infrastructure.

To hear NYCHA officials tell it, though, the agency is making strides despite continued underfunding. Officials speak of improved customer service and quicker repairs. In recent years, NYCHA has issued press release after press release about its progress in clearing out a backlog of 330,000 repair requests, cutting it down by as much as 95 percent.

“If you call us with a leak on Monday, what we’re saying is we’re going to send someone to your house within seven days,” NYCHA General Manager Cecil House told ProPublica. He said that the agency’s expectation is that even complex repairs of apartments should take about 15 days.

“While NYCHA is a very large and complicated organization with more work to do,” House said, “I do think we’ve made a lot of progress.”

But residents and NYCHA’s own numbers offer a more sobering picture. Residents, housing attorneys, and community advocates say that across New York City’s public housing developments, they’ve continued to fight for months, even years, to get the agency to fix falling paint, moldy walls, and water leaks.

“It’s not true. Let me just state that emphatically. It’s not true that repairs are getting handled in much of a different way than they’ve been handled in the past 20 years,” said Grant Lindsay, a community organizer affiliated with the Industrial Areas Foundation, a network of religious congregations and community groups.

Judging by the agency’s own metrics, while the housing authority has done better in some areas, it’s still performing far below expectations. Basic maintenance in February, on average, took about twice as long as the seven-day target, and longer than it did a year ago. A plumbing job, on average, took 49 days. A paint job took 53. Plaster work? Sixty-three days.

What’s more, NYCHA’s method of tracking repairs makes it impossible to tell whether underlying problems are actually being addressed. A closed work order may mean that a problem was fixed, said NYCHA executive Cecil House, or it may mean that “some component of the problem was fixed.”

Closed work orders also don’t convey whether the response was adequate.

Consider the water that has been dripping from a light fixture in the lobby of Santana’s apartment building in the Douglass Houses for more than a week.

“It was leaking water like a faucet,” said Santana’s downstairs neighbor, Ralph Pinkcombe. Concerned, he immediately called NYCHA and the fire department. “Everyone knows water and electricity don’t mix.”

NYCHA put in an emergency work order, assigned a ticket number, and sent somebody over to the building within a few hours. The fix? A bucket under the leak. A week later, the light fixture is still leaking, and when Pinkcombe called about it again, he learned that NYCHA had already closed his earlier ticket. When he told the rep the problem hadn’t actually been solved, he was simply given a new ticket number.

NYCHA’s media office said that the ticket closure was “an oversight.” “We apologize that it delayed resolution of this situation for the residents,” a spokesperson said, adding that it plans to send a plumber to follow up.

“Putting in a ticket number doesn’t mean anything here. It’s garbage,” Pinkcombe said. He’s lived in the building for nearly two decades, but it still surprises him that the agency allows dangerous conditions to persist. “These people will wait, they will wait until it’s a catastrophe for them to act upon it.”

Asked whether the housing authority has data that looks at actual problems fixed rather than work orders closed, NYCHA’s House said it would be “challenging” to aggregate the data that way.

“Our focus has been on trying to identify the components of all the problems. We use that data for staffing purposes, to help us track and count materials and costs. The system was designed with those things in mind,” he said. “It wasn’t designed to explain this complex system to the public.”

A court-approved settlement of a federal class action case last year offers another window into what NYCHA considers a repair. As part of the settlement, the housing authority agreed to address nearly all mold and moisture-related work orders within a week or two. The housing authority also agreed to fix underlying problems rather than literally painting over them.

But in a letter NYCHA submitted last month to the judge who approved the settlement, the housing authority argued that multiple work orders may be submitted for a given problem, and that each work order gets its own 15 days.

“So if they hire a plumber, that can be a 15 day work order. If they hire a plasterer, that’s another 15 days. If they hire a painter, that’s another 15 days. So that could be 30, 45, 60 days.” said Greg Bass, an attorney with the National Center of Law and Economic Justice, which helped bring the case. “They literally don’t agree that there is any specific limit to getting the actual job done to get mold and water out of the apartment.”

Bass said the plaintiffs are taking NYCHA back to court to enforce the settlement because they say the agency’s work to get rid of mold hasn’t come close to what the settlement requires. (NYCHA disputes that, arguing it is “not in systemic non-compliance.”)

“A frequent scenario is they come out and do what they’ve always done,” Bass said. “They wash down the moldy wall with bleach or detergent, and don’t address the underlying moisture. Mold comes back time and time again. We’ve heard horror story after horror story both before and after we’ve filed the lawsuit.”

Javonne Carl has lived that sort of horror story. It took her three and a half years and four housing-court lawsuits to get relief from the mold that plagued her apartment in the Smith Houses on the Lower East Side.

“I was constantly putting in tickets,” Carl said. When she’d call, NYCHA would tell her the ticket was closed out. “Why? I never understood it.” Sometimes they came, made a superficial fix, and the problem would come right back.

“It was so bad. So bad. The walls in the bathroom, they bubbled like bubble gum,” Carl recalled. They were so soggy that the bathroom sink fell off the wall more than once. In 2011 and 2012, a social worker who paid Carl’s teenage daughter home visits was so horrified by the extent of the mold in the apartment that she wrote letters documenting the conditions and even accompanied Carl to housing court to press for a remedy.

“Two children living in the apartment, aged 16 and 4 individually, are experiencing excessive coughing and skin rash problems,” the social worker’s October 2011 letter said. “Several items of clothing and furniture in the apartment have become covered with the mold and the odor associated with the mold.”

For years, that’s how she lived—bleaching walls and scraping mold, tossing out moldy clothes and furniture and replacing them, taking NYCHA to court and waiting at home for repairs. Carl said she had to miss work so often that she ended up losing her job at Whole Foods.

It took until this March for NYCHA to move Carl and her children out of that apartment and into another. The moisture problem, she says, was never truly solved.

For the first time in years, Carl said, she finally can breathe easy. Her daughters are loving the new apartment. But the past few years of wrangling with NYCHA have created real distrust.

“I really felt like I wasn’t getting no kind of assistance, to be honest,” she said.

This post originally appeared on ProPublica as “NYC Public Housing: Fixing a Leak With a Bucket” and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.