Yo is a popular smartphone application that enables users to send the word yo — just yo — to another user of Yo. The moment the urge hits — and for folks of a certain generation this is not infrequently — one simply taps a screen and … “Yo”! Yo’s designer, who released the app on April 1st, 2014, reportedly made the thing in eight hours. Soon after it was launched, not incidentally, it was hacked by three college students lazing around a dorm room. But by July, as reported in Business Insider, Yo was valued somewhere between $5 million and $10 million.

Strange times, here we are. Except that, in an era when the nation’s prime brainpower is increasingly invested in designing the next glitzy techno-fix, Yo isn’t that strange at all. Ask any Millennial if she thinks there’s a problem when an app that does nothing but deliver a shout-out turns technology geeks into mushroom millionaires and you’ll likely get a response along the lines of, Yo, what’s your problem, Luddite?

Yo, after all, epitomizes a generational ambition — Zuckerbergian in focus — to convince millions of smartphone owners that they need something that a decade ago would have been mocked as absurd. Resisting this trend — should you have the inclination to do so — is tricky business. The app craze is just an obvious example of consumer behavior stuck on what the psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls the hedonic treadmill.

This idea, rooted in the faulty hypothesis that more stuff equals more happiness, observes how our desires, once fulfilled, are immediately recalibrated to acquire something new and more ambitious. When these aspirations center on material goods, consumers easily go after the next new thing despite research finding no reliable connection between increased consumption and personal well-being. So the treadmill turns.

“The hedonic treadmill is an easy one to get on,” writes University of Texas–Austin psychology professor Art Markman on PsychologyToday.com. “It is easy to begin to take your current life for granted and to seek the next level of fulfillment. But the hedonic treadmill is not a necessary part of human experience. At some point, it is fine to just enjoy what you have.”

Or, at some point, you could also decide that you’ve had enough and, instead of resting easy with what you possess, you could conclude that, in fact, most of it stinks and, for the sake of one’s better self, should be turned into jetsam (or given to Goodwill). This is exactly what one of the most quietly rebellious social movements to come around in a long time is starting to do. And people are listening.

“Right now,society is deeply steeped in a consumeristic culture,” Ryan Nicodemus says as he prepares to attend a documentary screening in Somerville, Massachusetts. “We’ve been sold the American dream, one that requires accoutrements to fulfill our lives.” His voice gathers steam as his rhetoric intensifies: “The message is constantly shoved in our face. Soon we come to believe that if we buy all this stuff then we’ll be happy.” Lecture delivered, he sighs.

But Nicodemus is neither angry nor resigned. In fact, he and Joshua Fields Millburn, known together as the Minimalists, are an upbeat twosome (and best friends since the fifth grade) who comprise a kind of aw-shucks Ohio-based phenomenon for millions of followers seeking to lead less-cluttered lives.

Granted, such an endeavor — simplify and find meaning! — might sound twee, even Hallmark-ish in ambition. But do note that the sold-out screening Nicodemus was waiting to attend was called Minimalism: A Documentary About the Important Things(it was released to 400 theaters nationwide starting in May) and that Nicodemus and Millburn, the stars, had just come from New York to Somerville, where a crowd snaked around the theater, in the rain, hoping for a chance to see their favorite lifestyle gurus on the big screen.

Nicodemus and Millburn, both in their early 30s, are made for the exposure. They are fit, boyishly handsome, and strategically active on social media. Finely packaged as they are, their message disrupts the inner spirit of the American Dream, a myth they viscerally lament. They work from the radicalized premise that consumer culture “is not where we want to live our lives.” While Nicodemus acknowledges that “this is an old idea” — critics of consumption have been ranting as long as humans have been consuming — the Minimalists aim not merely to challenge America’s glorified consumer ethos. They want to replace it altogether.

To that end, they work hard, assiduously disseminating their message through a steady output of books, podcasts, interviews, and lectures, all stressing the value of having “more time, more passion, more experiences, more growth, more contribution, more contentment” through the pivotal act of “clearing the clutter from life’s path.” “We are focused,” Nicodemus says, “but not busy.” Busy is bad; focused is intentional.

Blending psychology, self-help, charisma, and compelling personal narratives (both defected from well-paying corporate jobs), the Minimalists come off as neo-Thoreauvian life coaches for the smart set. And while they aren’t terribly keen to characterize their message as one of sacrifice — “Minimalists don’t focus on having less, less, less” — Millburn occasionally wanders into his own private Walden, making a point of noting, for instance, that he owns only 228 items (a bragging right achieved, in part, by parting ways with, gulp, over 2,000 books). The average American household has about 300,000 items.

When I mention to Nicodemus that the Minimalists’ sharp critique of consumer behavior — punctuated by their aggressively pared down material existence — strikes me as a firebomb to the status quo, he laughs and jokingly shouts into the phone, “Down with the Man!” And when I comment that I could never, ever part with my books, he says, affirming the joy they give me, “Keep your books!”

He’s funny that way. And pragmatic. It’s as if he’s bending over backwards to confirm that he and Millburn are just a couple of regular, flexible dudes (a term Nicodemus used a lot during our interview) trying to live the dream without getting in anyone’s face — all the while delivering a message that shakes consumerism to its core.

And, to a plausible extent, it’s true. They are regular and flexible guys. And they are, it seems, living the minimalist dream. And they do appear to grate against no one in particular. Aspiration, for these fortunate young men, appears to have met reality. But don’t be fooled by all their smiles. These guys, at the end of the day, think most of your stuff sucks.

It should be mentioned that the Minimalists are experts in the art of intentional drifting. Nicodemus and Millburn relocate with little angst (in 2012 they moved from separate apartments in Dayton, Ohio, to a shared cabin in Montana) so long as it “adds value” to their lives. Notably, neither familial duties nor conventional job routines interrupt their itinerancy, which presumably makes their goals more achievable. Plus, it’s obviously easier to move when your life possessions practically fit into a backpack.

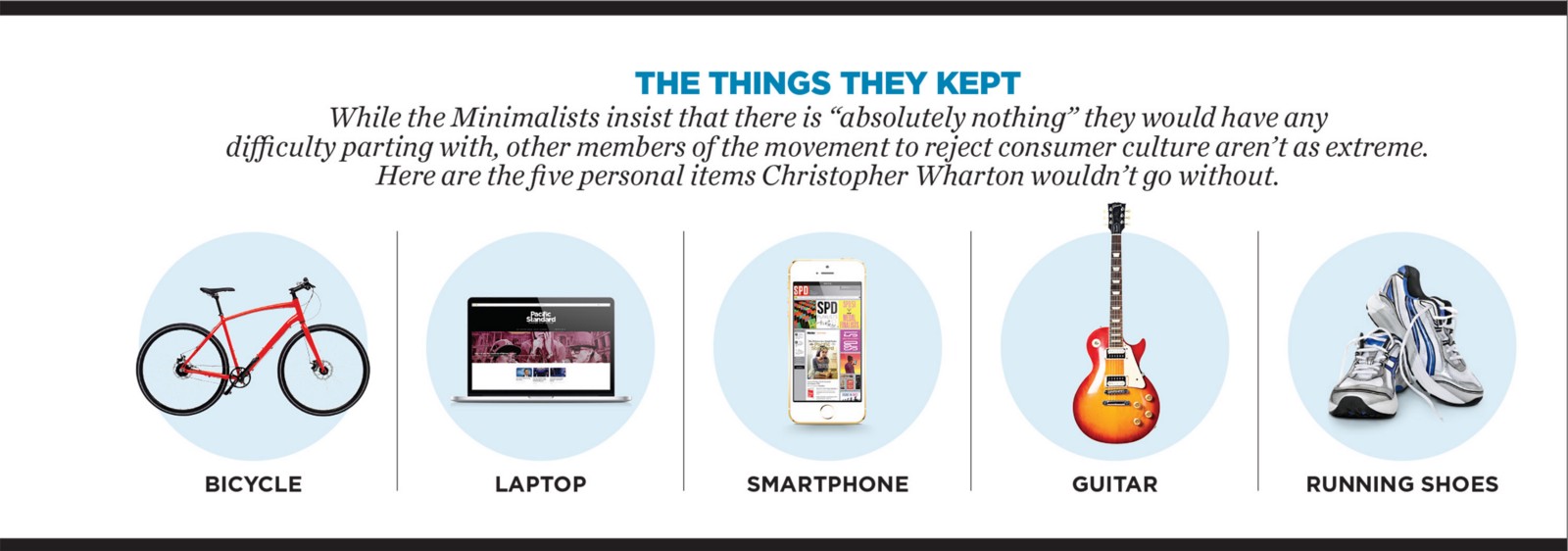

But for Christopher Wharton, an associate professor of nutrition and a senior sustainability scientist at Arizona State University, these factors — the job, the family, the rootedness — have proven to be of little hindrance in his quest to accomplish minimalist objectives. To the contrary, the spouse, the two young kids, and the considerable professorial duties of a tenured academic, provide the essential inspiration for pursuing a different version of minimalism, one that Wharton calls “voluntary simplicity.”

The term, coined by the social philosopher Richard Gregg in 1936, reflects, according to the Simplicity Collective, a “way of life that rejects the high-consumption, materialistic lifestyles of consumer cultures.” In this respect, voluntary simplicity is every bit an attack on Americanized consumer behavior as minimalism. Perhaps, given its accessibility, even more so.

What distinguishes Wharton’s perspective is that “it expands the idea of minimalism to show how it bears on finances, health, sustainability, and happiness.” It is, in other words, minimalism for those who can’t afford to make a living from minimalism; or, maybe more so, minimalism for those with maximal responsibilities.

Like Nicodemus and Millburn, Wharton isn’t cut in the revolutionary mold. When we met last year in Phoenix, he was, at least temperamentally, more Wall Street than Occupy Wall Street. But his message, as with that of the Minimalists, is nothing if not subversive to everything we’ve long thought enhances our sense of well-being.

When Wharton and his wife, Kelsey, started a family three years ago, Wharton worked to connect classroom lessons on health and sustainability with emerging patterns of domestic responsibility. The couple re-evaluated how they allocated their resources and found the results to be jarring. They saw too much waste — of time, money, health, happiness, and opportunities to help the Earth. And they saw a warped consumer ethic accounting for every whit of it.

“Those of us in the middle class on up have been sold a message that we have fewer choices than we really have,” he says, echoing Nicodemus. “We need to rebel against this idea, and we can do so by attacking basic consumer behavior.”

Thus followed the slow burn of a purge, starting with the family’s second car, an already paid-off Chevy Colorado. Wharton, who estimates that he saves several thousand dollars a year without it, admits “there are occasional hassles” that come with only having one car (a Prius) to negotiate the sprawl of Phoenix.

But he adds that, in addition to the financial savings, he has since put 2,000 miles on his commuter bike, reduced his carbon emissions, spent more time outdoors with his family, and discovered that “Phoenix is flat, the weather is tolerable, and there are networks of trails.”

Wharton’s mechanism for reaching the masses — one that he articulates as much for himself as for others — is a site he calls Practically Awesome. In a sense, Wharton’s how-to writings are a scattered panoply of self-help titles: “How to Create a Creative Kid,” “How to Have a Life Philosophy,” “Save $1,000 a Year With This Packed Lunch Toolkit,” “How to Have a Zero-Waste Day,” “How Much Should I Worry About My Weight,” and so on. He has much to say about toilet paper (no need for it), television (get rid of it), and food choices (recommended: sweet-potato quesadillas).

In the end, Practically Awesome adds up to something more holistic and ambitious than a series of life hacks. As reflected in the family’s choice to forgo the second car, Wharton argues that the ripple effects of our most basic consumer decisions (at one point he gives advice on what kind of underpants to buy — and how many pairs) directly shape everything that matters in life — health, happiness, financial security, sustainability, spirituality.

“Look at this as a social movement,” he says, as I scroll through a Practically Awesome post about how to give yourself a haircut.

The trick for these ministers of minimalism is to get us past a lot of excellent cost-cutting advice to reach the larger conclusion that simplicity works best as a complete lifestyle makeover. It may help — and perhaps it’s even essential — that minimalists and voluntary simplifiers tend to be unusually thoughtful people who consider their own interests inseparable from those of their families and communities.

Indeed, these guys put ideals into action with such a tender spirit of optimism you wouldn’t guess that real sacrifices were being made. Never, in fact, have such subversive ideas — reduce, end, or even reverse consumption — been expressed with so much unfailing decency and hopefulness.

It’s an odd, even historically unprecedented, style of rebellion. But Wharton vows, as he sheds his possessions, “to be deliberate about focusing on, and participating in, the good in the world.” And Millburn writes about Nicodemus that he “is the best person I know: he is habitually honest, caring, and loving.” It’s as if giving up material goods cleared space in the heart for a love fest.

But this sweet disposition leavening the minimalist message raises a question: Does kindness ever win the culture war? The most famous advocate for minimalism — a man named Peter Adeney, who goes by the moniker Mr. Money Mustache — suggests that it might not.

Adeney cultivates a more aggressive tone rooted more in the quest for personal pleasure than the ambition to do “good in the world.” Insisting that one should retire at 30, and backing up the claim with hard numbers on his own finances, he calls himself as “a freaky financial magician.” Adeney, according to his own assessment, counsels his followers in the art of “badassity.”

Badasses don’t play the Man’s game. A life of honest hard work for a corporation is, according to badassity logic, “nonsense.” Mustachianism sneers at “your middle class life” as “an Exploding Volcano of Wastefulness.” If Adeney’s media exposure — he outed himself with his full name in a New Yorker profile — is any measure of his success, this kind of aggression has widespread appeal.

But given the nature of our increasing discontent with consumer culture, Adeney’s attitude may be little more than entertainingly idiosyncratic. There may, in other words, be genuine hope for the more civic-minded ministers of minimalism to take a more community-centered lead in fundamentally shifting how we think about the place of material goods in our lives.

Art Markman, the University of Texas–Austin psychologist, seems to think so. He notes that “there are people who recognize that acquiring new things has not made them happier,” adding that the motivation to re-focus attention “on experiences rather than things” is important. He continues: “There is a lot of research suggesting that when you focus on experiences, you engage in activities that create positive memories and stronger connections to your friends and community.” Likewise, Amy Cox Hall, who researches neo-monastic communities as a visiting assistant professor of anthropology at Amherst College, sees the rejection of consumer culture as more of a community-minded effort centered on social justice than achieving a “personal gospel of prosperity.”

As for Wharton, who just started doing long bike rides with his three-year-old son alongside him, nothing could be more to the point. Optimism will always prevail as his guiding light into the brave new world of voluntary simplicity.