On the morning of January 29th, 1969, Santa Barbara News-Press reporter Bob Sollen received a call from an anonymous source. When he answered, the voice at the other end of the line rang out clear and urgent: “The ocean is boiling.”

For nearly 24 hours, gas and thick black oil had been bubbling to the water’s surface, and, with each lapping wave, the sludge inched closer to the California coastline. The day before, the workers on an offshore oil rig called Platform A were removing the drill pipe from a freshly bored well when gas and drilling mud erupted onto the platform. Though the crew managed to stopper the top of the well, the highly pressurized gas and oil continued leaking into the water through faults and fractures in the upper layer of the ocean floor.

Platform A was owned and operated by Union Oil, a petroleum company headquartered in nearby El Segundo, California. With no contingency plan and no federal regulations in place, it took Union months to contain the blowout. In all, three million gallons of crude oil spilled out into the Pacific, unfurling across more than 800 square miles of ocean, coating 35 miles of beach, and killing more than 3,600 seabirds and countless marine mammals and fish in the process.

Santa Barbarans of all ages mobilized against the profound degradation of their otherwise-pristine seaside city, long known as “The American Riviera.” Demonstrations took many forms: There were the dozens of local protests against Union, which saw residents lashing out at ecological injustice; there were grassroots factions like Get Oil Out!, which distributed pamphlets and bumper stickers and once famously dumped a bucket of oil onto the desk of a Union Oil executive; and there was the lawsuit against Union, filed jointly by the city, county, and state.

The blowout — then the largest in United States history — drew global attention, too, as images of oil-coated marine life circulated in news reports around the world. That reporting got people thinking about how to balance their desires for economic progress (and cheap energy) with the emerging idea that humans have a moral obligation to protect the environment.

(Photos: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

The spill was followed by decades of bipartisan environmental action: Members of Congress worked across the aisle to create the first Earth Day in April of 1970 as well as several key acts of environmental legislation. For Union Oil, the spill represented a colossal bungle, one exacerbated by its own executives’ apparent callousness. “I am amazed at the publicity for the loss of a few birds,” Union Oil president Fred Hartley infamously said after the spill.

It would be a stretch to say the oil spill precipitated the modern environmental movement. But the disaster certainly called forth a more tactical and coherent national effort, and imbued environmentalism with the kind of fervor that had already galvanized the push for women’s equality, civil rights, and peace in Southeast Asia.

There would be many more spills in the U.S. in subsequent years, but never again would industry and government officials be so ill-prepared. All that protest, and all that legislative change, thanks in large part to the fuss over “the loss of a few birds.”

I. “We Were Conservationists”

Long before the 1969 blowout, Santa Barbarans had already grown wary of the rigs sprouting up along the ocean horizon. But local activism — mirroring national interests — was already consumed by civil rights, feminism, and the Vietnam War. Plus, Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall had assured the city two years before the blowout that “you have nothing to fear; no leases will be granted except under conditions that will protect your environment.”

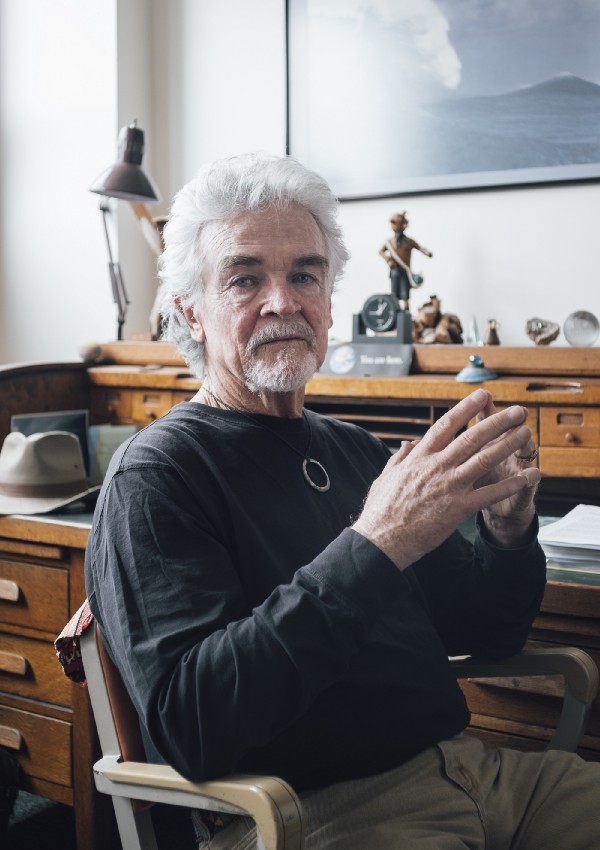

(Photos: Jonas Jungblut)

Susan Hazard (administrator with Santa Barbara Waterfront): I remember when they built the oil platforms. Until then, it was beautiful. It was just the moonlight on the water. I remember the oil companies saying when they built the oil platforms, they were going to obscure them with clouds, so that you would never see them. They were telling us whatever we wanted to hear to get it approved.

Harvey Molotch (former sociology professor at the University of California–Santa Barbara): These were the early days of offshore oil drilling, certainly in California the earliest stage really for anything that far offshore.

Bud Bottoms (co-founder of Get Oil Out!): We were invaded by the oil companies. We didn’t want that out in our oceans, you know? I mean, I spearfished, took lobster. I fed my kids out of the ocean for years.

Molotch: In those days Santa Barbara County was heavily involved in the oil industry, with lots of jobs and supply companies. There was a group on the County Board of Supervisors who were very, very close to the oil companies. Even in the city of Santa Barbara the oil industry had a presence.

Hazard: The oil companies had been doing their exploration, and ruining the trawling fields. Fishermen would drag their nets along the ocean floor and pick up all the ground fish, and then that’s what was feeding people. Dad would come home and say, “I’ve lost another net.” When there was no fishing, yes, dad would go to work for the oil companies to make some money. But I think he always held them in very low regard, because they didn’t care about anybody else.

Bob Sollen (former Santa Barbara News-Press reporter): I had been on the [News-Press] staff for several months, and the publisher called me in and said, “The federal government is selling oil leases.” All we had until 1969 were state platforms and drilling rigs, and we had enough trouble with those. The local attitude could not have been more opposed.

Bottoms: We were conservationists. We wanted to keep it a clean environment.

Rod Nash (founder of the Environmental Studies Program at UCSB): We had kind of a real change in the philosophical motivation of what used to be called conservation, and after the 1960s what was increasingly called environmentalism. We can mark the beginning of environmental attention to the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962.

Mick Kronman (Santa Barbara harbor operations manager): If anybody was to take responsibility for jump-starting the modern environmental movement, it would be Rachel Carson. But people have been concerned about the environment ever since they set foot on the Earth.

II. “There Were Dead Mammals, Dead Birds, Dead Fish”

Union Oil was founded in the Santa Barbara Channel in 1890. By the 1960s, Union had become the 11th largest oil company in the U.S., with operations around the globe. But the company was struggling to keep up with its larger competitors, due in part to heavy conglomeration in the industry. The federal government had leased some 5,400 acres of the seafloor below Platform A to Union, Texaco Incorporated, Gulf Oil Corporation, Mobil Oil Corporation, and Peter Bawden Drilling Company for more than $61 million (plus royalties on the oil the land produced), and Union was operating the oil rig for the group.

Platform A — one of the early federal offshore rigs in operation — tapped into a reservoir of highly pressurized oil and gas 3,000 feet beneath the ocean floor. Drilling at such depths requires precise procedures to counter the intense pressure from within the Earth to prevent oil and gas from rocketing to the surface uncontrolled. On January 28th, 1969, a blowout occurred when the pressure from below exceeded the pressure applied by Union crews from above. The explosion cracked the seafloor in multiple places; oil continued to slowly seep out even a year later.

(Photos: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

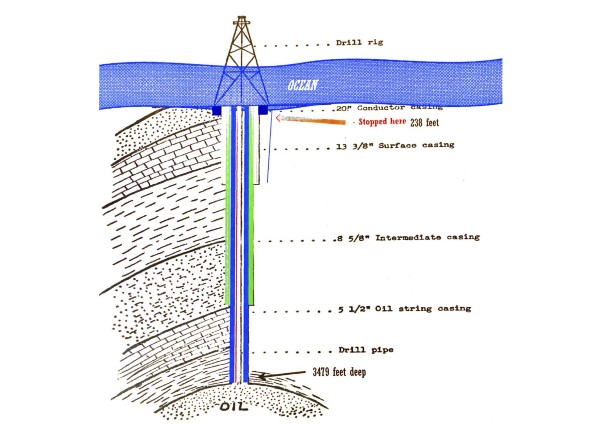

Bottoms: The drill went into this really fragile soil. They put a case around the drill, and the last, I don’t know how many feet, they didn’t have enough casing so they started drilling without it.

Barry Cappello (former Santa Barbara city attorney): When you drill an oil well, the first thing you do is you put in what’s called casing string. Then you put the second set of steel casing in, and then you put a third set of steel casing right to the oil reservoir. Because there’s a huge amount of natural gas in these reservoirs — the pressure’s in there, and, soon as you pop the cork, it comes out. And as it comes out, they actually use heavy, thick mud as a blowout preventer; the weight of the mud will hold the gas. Union put this first, 230-foot outer casing string in, but not the other two casings. They then drilled. The well is 3,400 feet down.

Bottoms: Union cheated on the last end of that well, and that’s why it blew out.

Sollen: The bottom of the ocean exploded.

(Photo: Jonas Jungblut)

Marc McGinnes (environmental attorney; co-founder of the Santa Barbara Citizens for Environmental Defense): And I want to just say how important Bob Sollen was to that whole environmental movement. Bob was all over this story.

Paul Relis (first executive director of the Community Environmental Council): Sollen was, in many respects, the thread that kept the early environmental efforts alive as a writer. The News-Press had a somewhat courageous editorial staff; they pretty much gave Bob free rein.

Molotch: I think Sollen was the first person to have an environmental beat in the United States. That was just unheard of. The New York Times didn’t have an environmental beat.

Relis: He was the go-to guy on the coverage, and the coverage was critical to the environmental movement because people were educated and political pressure came that way.

Sollen: We got an anonymous call. I answered the phone and they said, “The ocean is boiling!” I don’t know who it was, or what position they were in, but they were alarmed by it. For some reason I figured it was one of the workers out at the platform.

Molotch: It was just an utter shock that anything like this could happen. No one, I don’t think, imagined anything like that because it was unprecedented, not just in Santa Barbara but anywhere.

Cappello: This could probably never happen today, because no government agency would ever allow them to drill a well the way they drilled this well.

(Photo: Jonas Jungblut)

Nash: The oil didn’t come in [to the shore] for about two or three days, but it had a real emotional, visceral kind of impact on me and other people who were watching.

Relis: We hadn’t had big oil spills and it seemed so foreign to this place, this beautiful coastline — all of a sudden you go down to the water’s edge and it’s just like heavy, black soup.

Nash: It was like a shock of moral outrage kind of ran through you.

Relis: Somehow I finagled my way into a single-engine small plane that flew over the actual source of the oil spill. I remember looking straight down into this huge upwelling of black out of the ocean. And I just instantly thought, this is going to change the world.

(Photo: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

Bottoms: A week after the blowout you’d go to the beach and you couldn’t hear the waves. Because all the coast was black. You went to Hendry’s Beach [a county-owned beach in the city of Santa Barbara], there was no noise of the waves breaking. Just … slop, slop, slop, slop. And people just stood there and cried. All our beaches were black. You’d see surfers standing there with their boards, and their boards are covered in black.

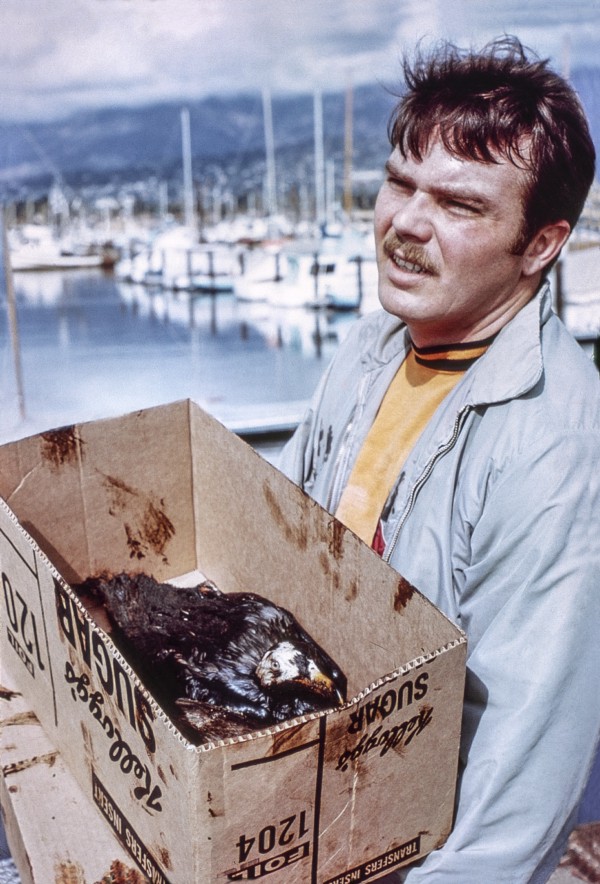

Nash: I can remember watching diving birds that go underwater and have to come up to breathe; when they came up through the oil, they were covered. They’re basically dead because it’s really hard to remove that oil from their feathers.

(Photo: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

Bottoms: As the birds would come out of the water, they would try to clean their feathers and they’d ingest the oil. People picked them up and put them in boxes, took them down to a cleaning station. There were thousands of birds; I don’t think they saved one of them.

Hazard: It was horrific. It was just oil all the way up as high as the high tide line. There were dead mammals, dead birds, dead fish.

Nash: Those are the pictures that made it around the world in the news services showing the birds on the beaches of Santa Barbara.

Bottoms: Sea lions took a real beating too, over on San Miguel Island. The babies couldn’t suckle their mothers because she’d have tar on her tummy, so that would kill them. It was a mess.

Molotch: Miles of beach — as far as the eye could see — covered in black oil. Beaches that you walked on, swam off of, just gazed at countless times. And the smell of oil was just everywhere.

Cappello: The stench!

McGinnes: The smell was pervading.

Hazard: It really smelled bad.

McGinnes: The conditions were such that the winds would carry the vapors ashore.

Cappello: You could smell it as far as City Hall.

(Photo: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

Steve Dunn (local Santa Barbara resident): Even months later, the entire Rincon Point [a world-famous surf spot in Santa Barbara County] at low tide smelled like dead fish. But the surf was fantastic.

Cappello: One of the things people forget about the spill is, it went on for months. Months.

III. “This Was a Joke”

Offshore drilling took off in the Santa Barbara Channel before anyone knew how to clean up oil and gas from a marine environment in the event of a spill, and nearly all of Union’s early efforts merely exacerbated the problem.

Immediately after the blowout, oil booms — devices that float on the surface to block the spread of oil — were deployed, but they broke apart in rough seas. When the booms failed, Union mixed chemical dispersants into the oil, but the chemicals themselves were hardly less noxious than the oil and did little to stop the ever-expanding slick. By the time it reached the coast, Union’s main strategy was to sop up the black sludge with straw — a method that proved somewhat effective two years earlier when, in what remains Britain’s largest oil spill, a supertanker ran aground off the coast of the United Kingdom and clean-up crews threw any absorbent materials they could think of onto the oil-slicked beaches.

Six months after the blowout in Santa Barbara, some beaches remained closed as tar continued to wash ashore at random, and the slick of oil in the open ocean lingered well into the following year.

(Photo: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

(Photo: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

(Photo: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

Kronman: Commercial fishermen were really distraught and frustrated and angry, and trying to help.

Manuel Gorgita (local fisherman): The oil company hired us to go out to the rig. We just set out the booms and towed them around with the boat — and hung on, because the wind was blowing and it was rough. Then we came back in and put booms across the front of the harbor entrance. They worked pretty good but they didn’t keep it out.

Bottoms: It came into the harbor really thick, clear up to the harbormaster’s office.

Nash: In the harbor, there was like three, four, or five inches of oil on top of the water, sloshing around. One of the first rules of boating is don’t spill fuel into the ocean; here there were acres of oil.

Gorgita: A couple times, to get all the oil out, we tied a bunch of fishing boats up along the docks, started ’em up and put ’em in gear, blowing oil out into the fairway then out of the harbor, and then we put the boom back across. We were there with the booms clear until the next November.

Relis: The first impression I had is how pitiful the response was.

Nash: When it finally did come in, it was a “black tide.”

Sollen: The oil would come up with the waves. They would roll back into the ocean, but it would leave the oil on the beach. They didn’t do any clean-up until it got on the beach.

Bottoms: The way they cleaned it up was they brought in straw. Bales and bales of straw.

Hazard: They didn’t have the oil response teams that they have now. We were totally unprepared for it. You know, what were we going to do?

Relis: I thought these oil companies and the federal government had sort of a game plan, but this was a joke. They were throwing straw down on the beach to lap up the oil with pitchforks and hiring people off the street! I mean, this was funky.

Bottoms: And they’d throw the straw out into the harbor too, and they’d take pitchforks and get convicts down there in little barges and lift the straw out of the ocean and drive the straw up the coast to a dump.

Relis: That was kind of eye-opening — that big companies and big government can be so incompetent.

Cappello: Today you have governmental agencies that monitor this. You can’t put a platform out without having a detailed plan on how you’re going to do it, what’s going to be involved, how you’re going to drill the wells, etc., etc. Then, there was nothing, no governmental agency. Zero.

Sollen: Union Oil said, “It’s nothing we can’t handle.” The company insisted it was not a great problem.

(GIF: Taylor Le)

Girard Boudreau (attorney representing Union Oil, Mobil, and Peter Bawden Drilling Company): We didn’t have some of the sophisticated stuff that they have today. But, I mean, there had never been an oil spill like that. The oil companies did a pretty good job of coming in there and cleaning that stuff up. There was no effort wasted for that. They spent a lot of money on clean-up — it was in the millions.

Frank Sarguis (attorney and former president of GOO!): There were those, encouraged by the oil companies, who said that there’s been oil in our beaches from the weak crust of the ocean shore in the channel.

Molotch: A whole lot of the banter comes out through the company spokespeople, who will just say whatever seems plausible from the standpoint of protecting the company or enhancing its interests.

Sollen: It was getting publicity all over the country, because I was getting phone calls from New York to San Diego. They wanted word from someone who knew what it was like out here, and they weren’t getting that from the oil companies.

IV. “They Wanted to Make Damn Sure They Didn’t Get This Fucking Oil on Their Shoes”

A citizens’ movement began in the days and weeks following the blowout, and “Get Oil Out!” was their the call to arms. They campaigned against Union Oil, circulating bumper stickers and pamphlets, writing letters to representatives, even trying to hand-deliver boxes of petitions to the front door of Richard Nixon’s Western White House.

Sollen: The thing just kept going on day after day. It was not under control.

Bottoms: I was in the General Electric office with two of the guys. I was so disturbed, I yelled out, “We’ve got to get the oil out!” And my boss goes, “Yeah, that’s good, get it all out, goo. G-O-O.”

Denis Hayes (coordinator of the first Earth Day): GOO! was reducing things to that kind of bumper-sticker level, which you really needed if you’re going to be communicating with large crowds.

(Photo: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

Bottoms: So I said, “Let’s run up a petition to get it out, to get the people of Santa Barbara to get it all out of the channel.” So we wrote up this petition, and we didn’t know anything, we were just conservation-type people. But we wrote the petition, and in no time flat we had over 200,000 signatures from around the world to get oil out of the Santa Barbara Channel. [At the time, the city of Santa Barbara had a population of 75,000.] Publicity was a big deal. One time we invited everybody to come to the beach with their mirrors and build a wall along the sand, and shine your mirrors on Platform A. We had kids that would go to the beach and get little bottles, little flasks of oil, there’d be 200 oil flasks and we sent them to every legislator, from city to the feds. Just continuous guerrilla warfare for the cause.

Sarguis: Lois Seidenberg, she was a tough gal, a registered Republican, smoked like a chimney. She was so pissed off at the blowout that she hired a helicopter and a pilot to take her out to the site of a new oil rig. And while they were hovering above, she threw fishing line down.

Bottoms: It was a fish-in. They were bringing in a new platform, so everybody went up there with their boats, and she hired a helicopter, and she had a fishing pole sticking out of the helicopter. They couldn’t haul that platform in from wherever it was made, because we were on the site where they were going to drop it.

Sarguis: She wanted to get coverage for the accident, for the blowout.

Bottoms: There was a guy who met with the Union Oil top dog and dumped oil all over his desk. There was a guy who was a bomber pilot during World War II, and he said, “I’ve got a crew that wants to take out that platform” and I was like: “I don’t know about that, just do what you want to do but gently. But I don’t want to know.” [The plan ultimately did not go through.]

Hazard: GOO! went on for years, but it just felt like, it was like David and Goliath, but David essentially had no weapons. Nothing. You just stand there and yell. And everybody just walked past us like, oh that doesn’t matter.

Boudreau: I was up there about getting some sort of a permit to do some oil drilling on one of the islands. It didn’t even have anything to do with the oil spill. And they were upset. They all showed up like it was the end of the world, booing and hissing. They were not ladies and gentlemen. I mean, Christ, I’m a lawyer up there from Los Angeles. I didn’t spill the oil, I’m doing my job.

Bottoms: We hit the state real hard, went up there with all of our petitions and pretty soon we got the state to act. They took out all the state platforms that were inside the three-mile limit. That was our first success. When Nixon got word of it all, he came out on a helicopter. The chopper landed on Leadbetter Beach [a city-owned beach in downtown Santa Barbara].

Hazard: I remember that this stretch of beach, that they were very active with bulldozers and cleaning it. They made it absolutely pristine. There wasn’t a piece of seaweed or a bird dropping, anything on it.

Bottoms: Nixon walked out onto the beach and there were a bunch of guys standing there with hard hats and they were raking the goo off the sand there.

McGinnes: They wanted to make damn sure they didn’t get this fucking oil on their shoes.

Hazard: These men were dressed in pure white, beautiful, brand-new white coveralls, with little tiny, thin-handle rakes, kind of like poking and raking at the sand like they were actually being industrious. There wasn’t a piece of oil in sight. Everybody was yelling at them that they should look at everything else, not just Leadbetter. But they looked at Leadbetter for about 10 minutes, then they got back in the helicopter and left.

(Photos: Kate Wheeling)

McGinnes: They were doing a Kabuki kind of a thing where, “this is an outrage, this is a tragedy, we must not allow these kinds of things to happen.”

Bottoms: But pretty soon everybody left, then the crowds left. And there was one car left in the parking lot, a big black limousine. So I stood there and these three guys came off the beach, took off their white suits and their hard hats, and put them in the trunk of the car — they were from the oil company.

Hazard: I just felt as though they’re not listening to us. They’re from another world, you know? Everything is insincere.

Bottoms: Nixon had a house in San Clemente, on the beach, so we went with all our petitions that night after we got loaded up with beer, down to San Clemente, and we delivered them to his door. Of course the Secret Service says, “You can’t come in here.”

V. “There Was No Law on the Books”

In the months that followed, a team of attorneys from the city, county, and state filed a joint lawsuit in February of 1969 against Union Oil and its partners for damages caused by the spill. Calculating those damages proved to be a tricky process, as there was no precedent for establishing willful misconduct. Finally, in July of 1974, the case was settled for $9.4 million — $4 million of which went to the city of Santa Barbara.

Cappello: I was a young assistant district attorney. Right around that time, the city attorney job came open. I applied for it, and I pitched the city council that they should file a lawsuit and go after the oil companies. I got the job.

Sarguis: Boy, Barry was like a dog biting your ankle that wouldn’t let go.

Cappello: And so the state attorney general’s office gave us a deputy attorney general, a guy named Ed Dubiel.

Edwin Dubiel (former deputy attorney general for California): I handled all that offshore stuff.

Boudreau: It was not a very friendly litigation, but Cappello was a damn good lawyer, and Dubiel was a professional.

Cappello: There was no law on the books, only an obscure California statute about littering the beaches. It was a misdemeanor. The fine was $150 a day. And that was it. So I came up with the theory that we would sue for loss of use of our beaches for our citizens.

(Photo: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

Boudreau: So there were five defendants: You had Union Oil, you had Mobil, you had Texaco, and you had Gulf, plus Peter Bawden Drilling Company. I was the lawyer for Union Oil, Mobil, and Peter Bawden Drilling Company.

Dubiel: It was the pollution of all the beaches that we were getting recovery for.

Cappello: The way you calculate damages is for loss of use. This is calculated on a loss of rental value as if you could rent out the property. When the dollar figure is multiplied by the acreage of each beach, including Santa Barbara, Carpinteria, and the state beaches all the way to Ventura, you’ve got some big numbers.

Boudreau: There was a lot of difficulty in the plaintiff’s case in showing the damage. On the real estate side, where they had the homeowners, that was what we viewed as the most serious case, because that clearly affected property values, at least for a period of time. Because there was oil all over the damn beach and everything. And the hotel/motel cases, they were a lot of trouble, because there was obviously a substantial depreciation on tourism. But those damages were generally pretty measurable.

Relis: Remember, this had huge economic consequences to the city. It was a tourist town.

Nash: Santa Barbara was probably the worst place in the United States for an oil spill to happen from the standpoint of the oil companies. The worst place. This is a town famous for its beauty. That’s what drove our economy here.

Relis: Who wanted to come and look at oil on the beach?

(Photos: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

Cappello: If you could file and prove willful misconduct, you can get punitive damages, and those are based upon the reprehensibility of the actual act. But how do you go about proving that? Well, there’s no government agency. So you hire experts. Well, where are you going to get experts to prove that it was not an accident? Everybody in the business works for the oil companies. We kept looking around.

Dubiel: So I went to the colleges and got experts in pollution.

Cappello: Finally, the University of California–Davis said, “Well, we’ve got a former petroleum engineer.” UC–Berkeley had a geology professor who’d had previous oil field experience. And those two guys had contacts. They got a guy, a retired driller for oil companies living in Santa Barbara. And a guy who used to run oil boats out to the platforms. That was our little team of experts.

Dubiel: Basically we looked at certain cleaner areas and counted the animals there, and then we took the area where the oil was and counted the animals there. Because nobody really has a count of what animals are in the ocean. And we had a biologist team from the university give us a cost of all the animals and we tried to get market value — sometimes it was protein value — of those animals. That was then multiplied by the difference between where there was no oil and where there was oil.

Boudreau: Dubiel was always talking about how the oil had destroyed the species of the fuzzy flatworm. And I remember the judge looking at him and basically saying to himself, without saying it: “Who gives a damn about the fuzzy flatworm? What about the fish?”

Cappello: We had meeting after meeting after meeting to try to figure out what happened. We got this through maybe 40 depositions, and our drilling people and our experts would say, “Find out about the casing string.”

Bottoms: They stopped using casing around the drilling point in the ground. It was cheaper.

(Graphic: Courtesy of Barry Cappello)

Dubiel: It was just negligence. What they did is, basically, they drilled it the same as they would do it on land. When they were out there, they didn’t calculate that there was a bunch of sand, so they put the regular casing they would put down on shore, and they should’ve went down another 3,000 feet with casing, and they wouldn’t have had the spill.

Cappello: We felt we could prove to a jury this was reprehensible conduct. Particularly when we got the partners to Union — Gulf, Mobil, and Texaco — to say they would never drill that way. So when we took the depositions of Texaco’s people, who didn’t drill it, we said: “If you were drilling a well, how would you do it? Would you do it this way?” They’d reply: “No, we don’t do it this way. But I’m not commenting that they did anything wrong.”

Dubiel: They had put down casing maybe 200 feet. Now when they drill there, they put down casing maybe 3,000 or more feet.

Boudreau: The plaintiffs were arguing that there wasn’t sufficient casing. My recollection is, there wasn’t anything wrong with the casing. That wasn’t the problem. The problem was that the blowout preventer didn’t work. And you got to remember, this is 1969. There wasn’t a lot of offshore oil drilling that far off, and there wasn’t a lot of experience like there is today. But my recollection is, we felt pretty sound on the defense on the casing.

Cappello: Union was just a sloppy operator. They were just a small-potatoes oil company, trying to run with the big boys.

Dubiel: The settlement was made to satisfy the city of Santa Barbara more than anything else.

Cappello: The total settlement was very close to $10 million. That was a huge number in those days — it’s worth $103 million today.

Boudreau: For what was then a hell of a lot of money today would be viewed as peanuts. I think it turned out pretty good for all parties concerned. Frankly, in my view, it was a very good deal for the oil companies. The fact that we were able to convince our clients to actually admit to liability in return for them not seeking punitive damages and waiving the jury trial, that was good for everybody. If we had not done that, and we had not agreed to that, that litigation probably would’ve lasted for, oh God, probably 10 years.

VI. “We Might Have Ourselves a Real Movement”

In the months after the blowout, as oil continued to surge from the cracked seafloor, local alarm solidified into a more coherent environmentalism, focused not just on protest but also real legislative change (and, for activists, a chance to take on environmentally unfriendly politicians, as was the case with the so-called “Dirty Dozen,” a group of legislators who were targeted for their poor records on conservation).

The movement that coalesced around the spill would produce Rod Nash’s Declaration of Environmental Rights, which was released on the one-year anniversary of the spill; the first Earth Day, celebrated by some 20 million Americans in communities across the U.S.; and, ultimately, the passage of legislation to create the environmental regulatory framework that still exists today.

(Photo: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

Hayes: Senator Gaylord Nelson was flying from Los Angeles up to Seattle for a meeting while the spill was going on. He was horrified by the extent of it from the plane window. So Santa Barbara played a key role in prompting him to develop the idea for Earth Day. In the run-up to the protests of the war in Vietnam, and the early days of the civil rights movement, there had been teach-ins on college campuses. He thought that would be a useful thing to do for conservation issues broadly.

Nash: The initial calls from people like Gaylord Nelson and Denis Hayes had been to have a kind of a teach-in on Earth Day, where campuses and schools around the country would devote that day to talking about human-environmental relations. A good idea, but my thinking was, yeah that’s like a one-shot thing, but how about a more permanent change, which could be creating a new major for students to study. I became the first chairperson of environmental studies, starting in the fall of 1970 when we began to offer that major.

McGinnes: It was one of the first environmental studies programs in the world.

Hayes: It was a matter of weeks when it became clear that this teach-in thing was a non-starter when it came to Earth Day; there was just no interest on college campuses, which were still consumed with the war in Vietnam and civil rights issues, the beginnings of feminism.

Kronman: There was a huge anti-war movement going on at the time. This was the draft: If you and I were the same age, we’d be sitting here like we’re sitting here now, growing our beards, smoking a joint, playing our guitars, and three months later one of us would be dead. That was the issue of the day.

Hayes: So we transferred the event out into communities. People could work on whatever was important to them: If your group was concerned about a freeway that was poised to cut through an inner-city neighborhood, then your Earth Day is just about fighting freeways. If you decided the internal combustion engine was the culprit for all that smog in Los Angeles and you wanted to pound an internal combustion engine apart with the sledgehammer, you could do that. That was the secret to the success.

Hayes: Nelson asked a Republican congressman from California named Pete McCloskey to be co-chair. He was an ardent environmentalist. A Republican being an environmentalist was not a setback in the late ’60s.

Sarguis: He’s conservative but very progressive at the same time.

McGinnes: I had a conversation with Pete McCloskey, saying: “We have to make sure that the word coming out of Santa Barbara isn’t just, ‘Get oil out.’ Because that’s not going to happen.” So then we decided on the first anniversary of the oil spill, why don’t we have a national conference on the concept of environmental rights. We have a professor at the University of California–Santa Barbara, Rod Nash, who could write a declaration — he’s a really good writer.

Nash: I took two things with me on a boating trip with a friend, out to one of the islands that had been hit by the oil spill: pen and paper, and a copy of Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence. I sat there on watch, piloting the boat, coming down the channel, porpoises jumping on the bow, and wrote the gist of what became this declaration. It seemed to me that it would be appropriate to use that same kind of form of a declaration to express the fact that nature was being oppressed by our civilization and that the rights of nature was a concept that made a lot of sense.

McGinnes: This was a new concept. Sure, we had legislation, but the conservationists — Gifford Pinchot and John Muir — said we should have wilderness because wilderness has value.

Nash: It was about damming rivers, it was about cutting trees smartly. But still harvesting resources and stringing out the yield of these resources over the long run.

McGinnes: It wasn’t about environmental protection; it was all about commerce.

Nash: People began to inject an ethical dimension into the discussion: that abuse of nature was not only unwise from an economic standpoint, but it was amoral. That created a tendency to deplore the spill not just for wasting oil, you understand, but for impacting other species and the entire ocean environment.

McGinnes: The Declaration of Environmental Rights is an important document, I think. I really do.

Nash: We presented it at the January 28th, 1970, celebration.

Sarguis: It was one of the first things that I’ve ever attended that had such a big turnout and rather significant people attending it too.

(Photo: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

McGinnes: I asked Paul Ehrlich if he would come to the conference. He was a rock star at the time; he had just written The Population Bomb. We got Senator Alan Cranston to come, David Brower, Stewart Udall, who, as the secretary of the interior, had made the decision to authorize drilling in the channel without public hearings. He came to the conference and said: “Mea culpa. I shouldn’t have done what I did. But we needed the money. The war in Vietnam was pressing us.”

Sarguis: The conference was sort of like the baptism for the movement.

McGinnes: We made a point of inviting Hayes to come, particularly, to talk about Earth Day.

Hayes: It was probably the first really giant crowd I had seen that felt passionately, I mean really passionately, about environmental issues.

McGinnes: On the day of the conference, people were blocking Stearns Wharf [a pier in the Santa Barbara Harbor], which was a base of oil operations.

Relis: I was just one of maybe 500 or 1,000 people who formed a blockade against trucks leaving the wharf.

McGinnes: We had this really, really tense confrontation. Hard-hat oil workers were saying: “You better get out of the way, sonny, I’m going to run this truck right over you.”

Relis: I remember a truck driver in a big rig coming out, and we’re all in front of him. It was dangerous, you know?

McGinnes: I went down there and looked at it before I went up and gave the opening talk. I could just sense that it was very explosive.

Hayes: I went out there and gave a talk and got a huge emotional response. I thought, we might have ourselves a real movement.

Relis: I talked to Hayes about Earth Day and basically thought, well, that sounds like a cool idea. So we closed the streets and held the first Earth Day.

Bottoms: We had lectures on all kinds of things: how to plant a seed, beehives, how to live off the land, all kinds of things like that.

Relis: We had about 5,000 people.

Bottoms: Paul started the ecology center. That was a little office we had downtown.

McGinnes: It was the second ecology center in the United States.

Relis: I’d seen the ecology center up at UC–Berkeley. It was sort of an active center for new ideas, new thinking. The first thing we did, we secured a storefront downtown, and we replicated what the Berkeley ecology center was: bookstore, meeting place, paintings on the walls. It was a real trippy kind of place. Then we decided to build a quarter-acre organic garden.

McGinnes: That was capacity-building, demonstrating organic gardening.

Relis: The next big move was to start a four-acre urban farm in downtown Santa Barbara, with rows of raised beds, chickens, a pig, and big compost piles. Early on it struck me that maybe Santa Barbara itself could be a laboratory for raising environmental consciousness and implementing ideas that could start here and move elsewhere.

Bottoms: We just had a bunch of crazy, wild things to stop fossil fuel. Because we knew that was a killer.

Relis: We weren’t going to purely regulate our way out of this. We were going to have to build a whole new infrastructure, and that oil infrastructure took about 50 to 75 years to build. Why would we think this was going to happen, an alternative infrastructure, was going to happen overnight?

McGinnes: The Santa Barbara event was a catalyst. There was a period of time, the ’70s, when there was an explosion of environmental law at all levels of government.

(Photo: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

Pete McCloskey (former Congressman): The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 got some impetus from the oil spill, but I’m afraid if the majority of the members of Congress had foreseen its impact, it never would have been passed.

McGinnes: NEPA created a new duty on the part of government: the duty to take into consideration the impacts of its decision-making in any environment, with respect to waters in the channels, with respect to mountaintops. While NEPA was being written and hearings were being held, it was not attracting a lot of opposition at all. All it was going to do was to say you had to do a study and then make findings. They didn’t think it was as significant as it turned out to be. NEPA didn’t take the next step, which California soon did, when it followed up within the year with the California Environmental Quality Act, which was like NEPA except it actually mandated denial of projects. It said, if you see problems that cannot be avoided or mitigated, you have to deny the project.

Relis: When you have so many well-connected citizens who can get on the phone and call their congressperson, or, who knows, the president, that helps.

Hayes: Now Nixon, by all accounts, he was not much of an environmentalist. But he was a hell of a politician and he saw this as something that might form the basis of some sort of a threat.

Relis: I’ve heard rumors, though, that Nixon was prompted to adopt a more environmental position because he was so unpopular with the young. They thought that might be an opening to get somewhere.

Hayes: So a not very pro-environment president became the guy who created the Environmental Protection Agency with an executive order.

McCloskey: And it was the action of thousands of young people after Earth Day in 1970 that took out seven of the 12 “Dirty Dozen.” The Earth Day organizers had $30,000 left to spend, and [created] an organization that took on the 12 incumbent congressmen by focussing student action on the election day, two in the Democrat primary, and the other 10 in the November elections.

(Photo: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

Hayes: They were all people who had really bad environmental records. They were all from districts where we’d had strong organizations and where we had one big environmental issue they’d been on the wrong side of. The very first one to get hit was a guy named George Fallon. Taking out Fallon just changed the dynamic dramatically. That was like the shot heard around the world.

McCloskey: That really kicked off the 24 years of bipartisan environmental protection laws.

Hayes: That helped create the context in which the Clean Air Act passed overwhelmingly. It just created a seemingly unstoppable force that continued for the next four or five or six years — we had the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Superfund Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. Just, bam, bam, bam, bam. We were striking while the iron was hot.

Relis: In the early ’70s, there were lots of moderate Republican leaders who had no problem with conservation, or protecting the environment. That wasn’t viewed as a partisan, narrow interest. It was like, “Oh yeah, that makes sense, you don’t want to spoil your own nest.”

Boudreau: It was a time in which people were able to compromise and do the best they could, instead of the environment we now see out there, where everybody’s at their throats all over the place.

(Photo: Courtesy of Bud Bottoms)

Hayes: But even then, you had the new core of the Republican Party, this arch-conservative base from the South that was not too happy with any of this environmental stuff. The roots of this new base, you can find back at the time of the first Earth Day.

Relis: Now we actually do have the tools: solar and wind technology. We have the policies, we have the entrepreneurs and the capital. To build this future and then find ourselves suddenly faced with a mindset that just wants to go back to the lowest-grade petroleum economy, it’s just unbelievable. You almost couldn’t fathom such a situation.

McGinnes: Action, reaction. We made a lot of progress in the ’70s, and then there was a strong reaction against it. It’s been hanging on ever since, in a way.

Story production and design by Varun Nayar, Taylor Le, and Nick Hagar.

These conversations have been edited for length and clarity.