A new paper finds that minorities still aren’t getting the mental-health treatment they need.

By Dwyer Gunn

(Photo: Mark Mainz/Getty Images)

Policy changes meant to improve access to mental health care are among the manynotablerevisions included in the Affordable Care Act. And new evidence suggests those changes did just that: A recent paper by Timothy Creedon and Benjamin Le Cook in the latest edition of Health Affairs concludes that mental-health treatment rates for people with “serious psychological distress” increased significantly in 2014. Unfortunately, those gains weren’t equally shared, and a substantial racial gap in mental health care treatment persists.

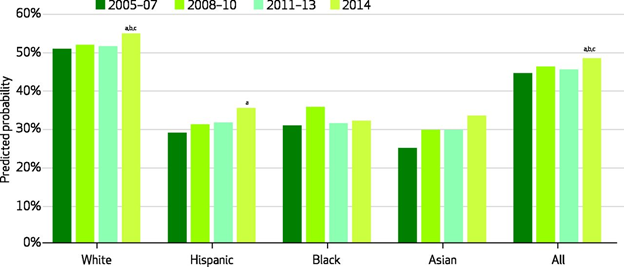

The chart below illustrates trends in mental health care treatment in the pre- and post-2014 period. White Americans continue to receive mental-health treatment at much higher rates than other minorities. Despite dramatic increases in health insurance coverage, African Americans in particular have seen no statistically significant improvements in treatment rates.

Any past-year mental-health treatment among people with serious psychological distress. (Chart:

Health Affairs)

Creedon and Le Cook ultimately had the following rather depressing insights to offer:

Although whites, blacks, and Hispanics alike experienced coverage gains in 2014, only whites and Hispanics saw corresponding increases in mental health treatment. While coverage increased for blacks at least as much as it did for whites, the mental health treatment rate for blacks remained flat in 2014. And despite clear coverage gains across multiple racial/ethnic groups, in no case did treatment rates for substance use disorders increase. This suggests that gains in insurance coverage alone are not likely to push forward meaningful reductions in mental health treatment disparities or increase consistently low overall substance use treatment rates.

If improved access won’t do it, what can reduce mental-health treatment disparities? A second Health Affairspaper in the same issue (which is entirely focused on behavioral health) attempts to answer that question by highlighting three prominent barriers to treatment: a shortage of mental-health providers in low-income communities and an overall dearth of providers who accept Medicaid; stigmas and distrust around behavioral-health treatments within minority communities; and various forces (discrimination, poverty, inflexible jobs) that may make it harder for minorities to complete treatment.

The authors of the second paper, led by Margarita Alegría, point out that mental-health treatment isn’t a one-size-fits-all proposition, and treatment models based on the preferences of white patients may not serve minorities as effectively. “A qualitative study of these preferences in the behavioral health patient-provider encounter found that the following three themes were consistently described by African American, Latino, and white patients: listening, understanding, and managing differences between patients and providers,” the authors write. “However, descriptions of the themes varied across the groups. For African American patients, listening involved the provider’s recognizing the patient as the expert on him- or herself. For Latino patients, it meant clearly paying attention to what the patient is saying, and for white patients, it meant making the patient comfortable enough to express his or her feelings.”

Alegría and her co-authors suggest a number of reforms that might reduce mental health care disparities: mobile medical clinics, of the type currently used to provide primary care to hard-to-reach populations, might also provide mental health care treatment; mental-health tele-medicine services could be expanded, which would also allow non-English speakers to access a more diverse array of providers; behavioral health services could be integrated into other social service programs; and culturally sensitive marketing campaigns could be implemented to increase awareness and reduce stigmas.

The authors also propose an interesting solution to the provider shortage: training community health workers — lay personnel who are generally drawn from the communities they serve — to provide behavioral health services. Community health workers used to primarily work in developing countries, but they’re being increasingly utilized in the United States to reach under-served populations, and the evidence overwhelmingly indicates they can reduce costs and improve outcomes.

||