With playdates replacing free childhood play, it’s upper-class families who set the social norms — and working-class families who pay the price.

By Malcolm Harris

(Photo: Ramsey Beyer/Flickr)

Kids used to play outside more. They would hopscotch through the streets, assembling games of stickball and breaking glass soda bottles for fun. Parents would tell their children to be home for dinner and then forget about them until dark.

That golden age of unstructured play was real — scholars place it in the second quarter of the 20th century — but the children who lived it are now senior citizens. If you’re currently alive, you probably played less than your parents did. Between 1981 and 1997, for example, six- to eight-year-olds lost 25 percent of their play time. We aren’t romanticizing some fictional American idyll — kids really are playing less today, even if you include video games. And for some kids, even play is now a regimented and supervised activity.

As a social phenomenon, playdates are something like private schools. Wealthier parents remove their kids from public and sequester them somewhere with a guest list and a cover charge. Mose uses the term “enclosure” — when a public or common resource is fenced and privatized.

We live in an era of the playdate, when aspirational parenting means being your child’s agent and chauffeur. The idea of kids so busy they need adult secretaries to pencil in time with their friends is both silly and real. Take New York mom Tamara Mose: Her son and daughter’s weekly schedule includes piano, Kumon (a chic approach to private tutoring), taekwondo, regular tutoring, dance, and soccer. She’s lucky if she has time for a playdate.

Mose is a professor of sociology at Brooklyn College, and when one playdate connection turned into an invitation to deliver a talk about her first book, she became more interested in the repercussions of the phenomenon. Were other parents using playdates for professional networking? “I started noticing that I was gaining some kind of benefit through the playdate experience,” Mose tells me, “and I thought, ‘I wonder if this is a thing.’” The result is The Playdate: Parents, Children and the New Expectations of Play, a book-length study of playdate dynamics in New York City.

(Photo: NYU Press)

According to Mose, the biggest difference between simple play and an official playdateis that playdates are work. Playdates aren’t just scheduled, they’re prepared. They have expenses, and they can succeed or fail. A parent who serves the wrong kind of crunchy cheese snack could be jeopardizing their family’s place in the social hierarchy. Kids play, adults — or, more accurately, moms — make playdates.

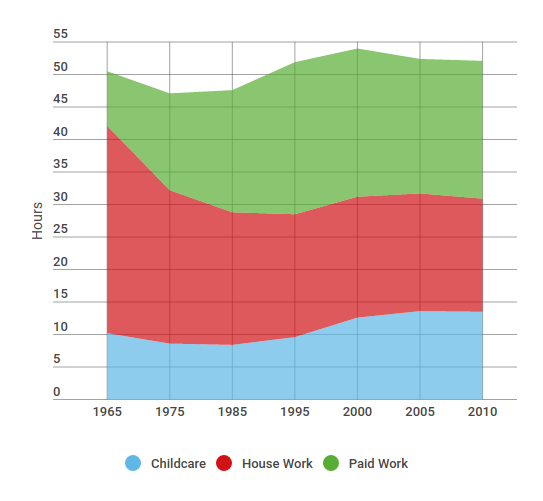

The question at the heart of The Playdate is why do moms bother? The dates that Mose describes are labor-intensive and anxiety-ridden. A Pew analysis of time-use surveys found that average weekly hours of work for mothers increased slightly between 1965 and 2011 as a significant decrease in unpaid housework was offset by increases in waged work and childcare. Weekly maternal childcare hours increased from 10.2 to 13.5.

So what purposes, exactly, do playdates serve?

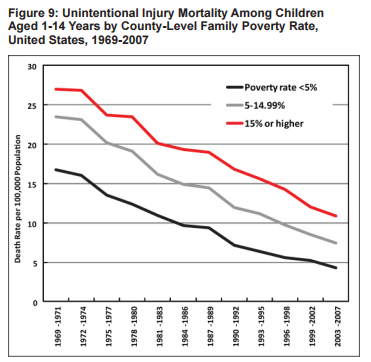

One explanation for the emergence of supervised play is that American parents got more serious about protecting their kids from harm. An evolutionary psychologist might point to declining birth rates and a historic shortage of back-up children. Death by unintentional injury for kids under 15 has fallen by more than half since the early 1970s; maybe the golden age of play was really a plague of parental negligence. Maybe playdates save little lives.

There might be some truth to the safety justification for playdates, but not much. Sociologist Annette Lareau coined the term “concerted cultivation” for the kind of parenting that involves a full schedule and constant oversight. Lareau contrasted concerted cultivation with the “natural growth” style, and found that both were class-linked, with upper- and upper-middle-class moms practicing the former, and working-class and poor moms the latter. It’s a pattern that Mose found in her research as well, with rich white moms setting the playdate standard. If concerted cultivation and playdate parenting were responsible for the drop in child-killing accidents, we would see a class division in the data.

(Data: Pew Research Center)

In fact, childhood injury mortality has declined (in absolute terms) more in high-poverty counties than in low ones. Kid safety has more to do with general crime rates (child victimization is down across the board, from homicides to kidnappings to sexual assault) and with seatbelt-buckling than with helicopter parenting. “There’s never been a safer time to be a kid in America,” the Washington Post’s stats-based Wonkblog declared, and as automated cars replace human drivers things will only get safer.

Playdates, like other elements of the concerted-cultivation mode of parenting, are about a different kind of security. “Given the precarity of work in general — people are not working for companies for 20 or 30 years the way they used to — there’s this threat that the economy could crumble at any moment,” Mose says. “So what you find is there’s this learned fear that parents have for their children, because we don’t know what the economic situation is going to look like down the road.” Managing a child’s play schedule ensures they don’t pick up any bad influences that will steer them from the path to college and success on the job market.

Like royal marriages, concerted parents set up playdates that are socially advantageous, for the parents themselves and for their children’s imagined futures. “Parents are unsure of what is happening in terms of their children’s future, and we want [children] to be prepared, so we over-prepare them,” Mose says. “What we do in the playdate is create a play that is mediated at every level. And when it’s mediated at every level, parents think that they can determine which direction they’re leading their child, and maybe that offers them some type of security.”

As a social phenomenon, playdates are something like private schools. Wealthier parents remove their kids from public and sequester them somewhere with a guest list and a cover charge. Mose uses the term “enclosure” — when a public or common resource is fenced and privatized. Brooklyn developers brag about the borough’s diversity, but the parents Mose interviewed were using playdates to shield their kids from people who weren’t like them. The app MomCo even lets moms (a selfie is required for “gender verification”) search for suitable matches from their smartphones.

(Chart: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services)

When wealthier people don’t use a public resource, it tends to degrade. Not because the rich hold things together, but because the government cares less about people who aren’t rich. This goes for the literal paving on streets, but also the symbolic space for unstructured childhood play. In 2014, South Carolina mother Debra Harrell was jailed for leaving her nine-year-old daughter in a park while she worked at a nearby McDonald’s. A Reason poll commissioned afterward found that average Americans don’t think kids should be allowed to do anything more independent than play in the front yard until they’re 12 years old. Natural growth parenting has been stigmatized and even criminalized.

Upper-class parenting practices that require a surplus of time, money, and private space set the standard for comparison. As a black mother routinely engaged in interracial playdates, Mose describes the pressure to make sure her children play the right way: “I always wanted to present as a decent black family because I know of the stereotypes out there about black families and black children,” she says. “So I always wanted to make sure my home was clean, I always wanted to make sure that appropriate food was being offered, and appropriate meaning organic or fruits and vegetables, not junky food or anything like that.” With professional connections and social prestige up for grabs, a playdate is not a game.

But, as Mose reminds me, there are also higher stakes. “We are reproducing inequality today through the enclosure of a playdate,” she says. “Through the privatization of play, we are reproducing inequality in our children.”

||