Members of the media provide more scrutiny for candidates they expect to win—and they always have.

By Seth Masket

Hillary Clinton during the fourth day of the Democratic National Convention on July 28, 2016; Donald Trump during the CNN Republican presidential debate on December 15, 2015. (Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Over the past few weeks, a narrative has begun to emerge that Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump are being held to different standards by the media. Trump, critics suggest, is being given a pass on many issues on which he is either uninformed or clearly lying. This moment may have been crystalized in last week’s interviews with Matt Lauer (along with the critical #LaueringTheBar Twitter hashtag that followed), but concerns go well beyond that night.

So what’s going on here? There are plenty of hypotheses about why the media might be treating the candidates differently, from longstanding distrust between Clinton and campaign reporters to the media’s unusual sets of challenges when covering Trump. But one simple reason is this: The media expects Clinton to win.

Years ago, John Zaller and Mark Hunt (full disclosure: Zaller was my graduate school mentor) reviewed decades of media coverage of presidential campaigns. Their aim was to measure how often the media itself initiated negative coverage of the candidates, rather than simply reporting on another candidate’s criticism. (Details of this collection can be found in Zaller’s unpublished book on media politics.) They were able to calculate the percentage of media-initiated negative coverage of every Republican and Democratic presidential candidate between 1968 and 1992.

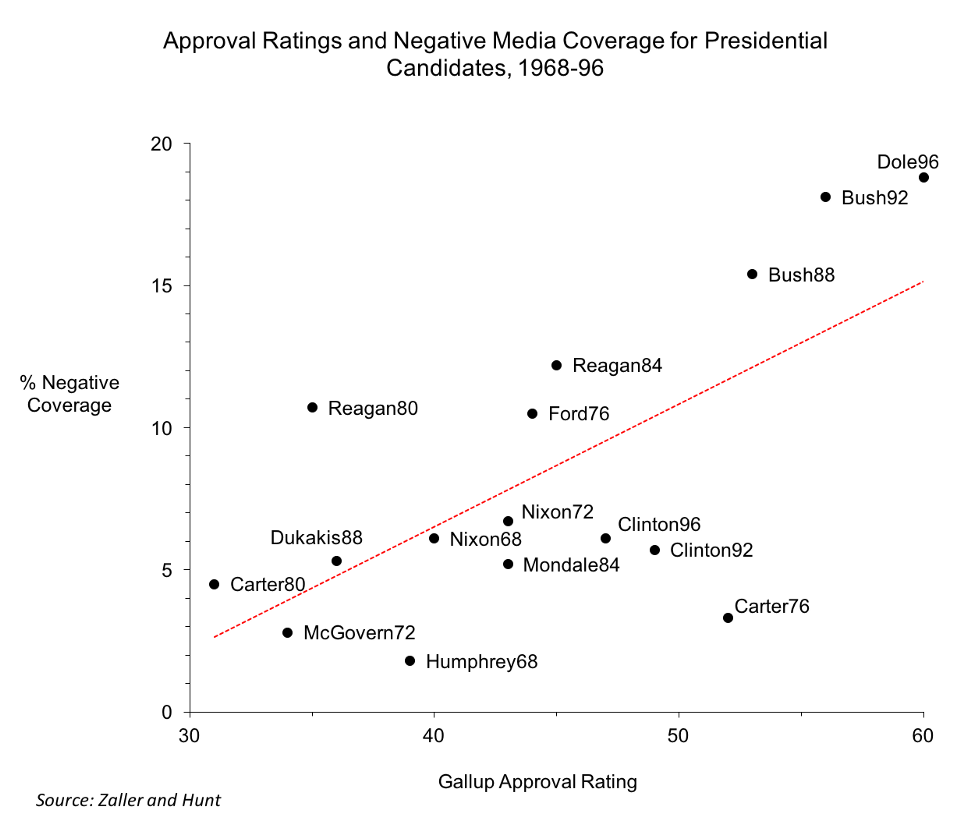

The scatterplot below shows the percent of negative coverage of the presidential candidates, charted against the candidates’ Gallup approval ratings around Labor Day of the election year.

The most notable thing in this figure is the upward trend in the data. The more popular a candidate was, the more negative coverage he received. One interpretation of that might be that negative coverage was good for candidates, but that doesn’t seem very likely. The more plausible interpretation is that members of the media provide more scrutiny for candidates they expect to win.

This is a pretty reasonable bias to have. Good campaign reporters have limited time and attention. Why not have them spend more of their efforts dissecting the person more likely to become president? Why waste energy scrutinizing George McGovern, when he was so clearly going to lose?

Another bias pretty apparent in the above graph is that incumbents get more scrutiny than challengers. That’s also understandable — incumbents have a highly visible record that’s easy to comb through. Even though Bob Dole, who got the most negative coverage in the above analysis, wasn’t an incumbent, his very public career in the United States Senate and his two previous presidential runs made him easy pickings for criticism. It’s much more challenging to scrutinize a small-state governor.

In some ways, Clinton has both factors working against her. Although her polling advantage isn’t enormous, she’s been in the lead since the contest began. Journalists, with good reason, expect her to win, and they’re providing tougher coverage of the person they think will be president.

And, of course, Clinton isn’t an incumbent. But given her two terms as first lady and her recent four years of service as secretary of state under the sitting president, she’s being treated as one. She’s got one of the longest records in the public eye of any person to seek the presidency, giving reporters plenty to chew on.

This is not to dismiss other ideas about different standards across the two candidates. Clinton may be getting singled out for tough coverage for some deeply unfair reasons. But if she is being held to a higher standard, the simplest reason is that she’s probably going to be president.