Since the country watched the World Trade Center collapse on September 11, 2001, anxiety over Islamic-induced terrorism has become as American as apple pie. But as it turns out, those fears may be somewhat overblown: According to new data, attacks by home-grown, right-wing extremists have killed almost twice as many Americans as jihadis in the 14 years since 9/11.

The New America Foundation’s International Security Program, which keeps an ongoing count of deadly attacks since 9/11, indicates that attacks on America by self-styled jihadists have killed 26 Americans since 2001, with the 2009 Ft. Hood shooting’s 13 fatalities registering as the deadliest. By contrast, right-wing extremism, like last week’s mass shooting in Charleston, South Carolina, has killed 48 people. And while the vicious execution of nine African-American church-goers by white supremacist Dylann Roof is a “particularly savage case,” as the New York Times puts it, it’s not all that uncommon.

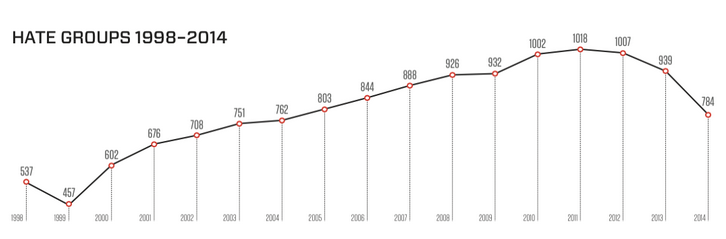

The Southern Poverty Law Center has suggested this for years; According to its analysis, right-wing hate groups have been steadily on the rise for the last two decades, and a domestic terrorist incident has occurred every 34 days on average.

“There’s an acceptance now of the idea that the threat from jihadi terrorism in the United States has been overblown,” University of Massachusetts professor John G. Horgan told the New York Times. “And there’s a belief that the threat of right-wing, antigovernment violence has been underestimated.”

But why, then, do Americans fear terrorism wrought by foreign agents rather than the threats growing in their own backyard? Consider Americans’ anxiety over the first confirmed Ebola case on U.S. soil during the height of the 2014 African epidemic. Despite the fact that U.S. health authorities had the Ebola cases well in hand (a few patients made full recoveries), Americans seemed more panicked over catching the deadly plague than they did, say, driving their cars to work. Writing in Psychology Today, Dr. Richard Leahy examined the cognitive processes at play during this hysteria:

Part of this is that once we activate a concept—like “Ebola”—our minds naturally search for examples of the feared disease. This is known as “confirmation bias” and leads us to focus on more information about Ebola, a tendency to discount evidence against the threat, and relying on our emotions to estimate risk.

Once the threat system is activated it looks for more threat. We are now in the “better safe but sorry mode” so we are reacting intensely, quickly, and emotionally looking for more evidence that we are at greater risk. We get angry at people who try to put things in perspective because this is equated with letting our guard down and endangering everyone.

A lot of this strange disconnect in our fears is simply subjective. According to David Ropeik, former director of risk communication at the Harvard Center for Risk Analysis, experience and culture tend to shape our fears and anxieties more than rational, statistical odds; we’re more likely to fear things we’ve had first-hand experience with than we are to dread abstract, distant threats. Even that fear of snakes and sharks, statistically insignificant threats to our livelihood, may stem from our horrifying experiences watching Anaconda or Jaws in theaters.*

This logic extends beyond exotic threats like terrorism or Ebola to more commonplace ones. Consider American fear of crime: A recent survey from Chapman University of 1,500 confirms that most Americans think all types of crime have become more prevalent—despite the fact that crime rates are at their lowest level in some 20 years. “When we asked a series of questions pertaining to fears of various crimes is that a majority of Americans not only fear crimes such as, child abduction, gang violence, sexual assaults and others,” lead author Dr. Edward Day said in a release. “But they also believe these crimes (and others) have increased over the past 20 years.” Chances are, this is because of our regular experience with crime.

The more we’re bombarded with fear-mongering images, the more we fear the monger’s imminence.

Apart from experience, culture matters, and America’s culture has been one of perpetual fear. This can be partially attributed to the media’s fixation on covering violent crime, terrorism, Ebola, and shark attacks—”it bleeds, it leads” being the mantra of the cable-news era. Research backs this up: A 2003 study in the Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture found that fears of crime “may be ‘natural; reactions to the violence, brutality, and ‘injustice’ that are broadcast to living rooms on a daily basis.” It’s certainly true that the mass media shapes our perceptions of criminals as well; a 2014 study by the non-profit Sentencing Project found that the media reinforces racial stereotypes of African Americans as criminals—a perception made so pervasive it now shapes the criminal justice system. The more we’re bombarded with fear-mongering images, the more we fear the monger’s imminence. Take again the 9/11 attacks: The visceral, horrific image of the planes crashing into the World Trade Center has been burned into our cultural conscience, enshrining Islamic terrorism as the threat of all threats to American lives.

This isn’t necessarily bad. After all, irrational fears are simply part of human psychology, shaped by pre-existing culture and subjective experience. But America’s propensity to utterly freak out has led to some horrific practices—rendition, torture, and the like—that have substantially lowered our standing with the rest of the international community, according to the Pew Research Center. Re-focusing our efforts on combating statistically more probable threats isn’t just a matter of rational thinking; if the past 14 years of the Global War on Terror are any indication, it’s a matter of sound policy as well.

*Update—February 22nd, 2019: This post had been updated with the correct description of David Ropeik’s former position at the Harvard Center for Risk Analysis.