Bombay Dost, the first registered magazine to serve India’s gay community, has battled Victoria-era law and widespread social stigma — now, it’s facing the decline of print magazines.

By Bhavya Dore

The unveiling party for the 2016 issue of Bombay Dost at the Mumbai Press Club. (Photo: QGraphy)

Some time in 1990, Ashok Row Kavi got a call from the Indian consulate in Quetta in Pakistan. “We have heard you have brought out some magazine,” the man on the line said, according to Kavi. “Many people have come asking for it. What is it?”

Kavi, an openly gay journalist and activist, had just released the first issue of a newsletter aimed at gay men named Bombay Dost (“Bombay Friend”). When he told the caller what it was, he heard the man on the other end slam the phone down.

Kavi and the other founding editors, all from Mumbai — then called Bombay — couldn’t have anticipated the international demand. In 1990, India’s economy was yet to be liberalized and being gay was, and still is, both legally punishable and socially stigmatizing. The HIV crisis was peaking in India, and the gay movement was fighting for its life, Kavi says. Setting up a magazine was Kavi’s way of calcifying a sense of community among the country’s invisible population; he never presumed it would become a lifeline for so many — in the early years, letters also poured in from Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Iran. “How it reached central Asia, I will never know,” he says.

For over a decade, Bombay Dost challenged social taboo byhelping readers come out and come into their own. Fulfilling that mission wasn’t easy, and the magazine briefly shut down in 2002 due to logistical difficulties. When it returned in 2009, Indian law had briefly become more hospitable to gay people. Today, however, Bombay Dost faces a new challenge: As it competes with online publications, the magazine must make the case for the print product, and its persevering power to bring the LGBT community closer together.

Last month, Kavi, now 69, and his fellow magazine co-founder Suhail Abbasi, 56, ripped the shiny silver wrapping paper off of the magazine’s 2016 edition in front of a small crowd ofjournalists, activists, and well-wishersat the Mumbai Press Club. The glossy cover reflected the side profile of the Bollywood actor Manoj Bajpayee, hailed last year for his performance as a gay professor in the biographical drama Aligarh. Bajpayee himself stood beside Kavi in a blue shirt and jeans, brandishing his own copy; theater and film actress Dolly Thakore was also in attendance. The starry launch party marked 26 years since the magazine began publishing as a 16-page newsletter-style publication.

India had seen other gay-specific publications before Bombay Dost, but the newsletter becameIndia’s first gay publication to be registered, which is a bureaucratic requirement that allows a publication to be sent in the post. Funding for the early issues was put together by activists and the founders themselves. After the first issue — priced at Rs 80 ($1.50) — the group thought they’d only be able to put together two more issues. But then a rich donor came forward with Rs 500,000 ($7,490). “That,” Kavi says, “sustained us for another five issues.” With more donors like that one, the magazine pulled through its initial years.

In the first four years, the magazine wasn’t just a printed publication, it was an all-purpose platform. In the early years, the editors received up to 3,000 letters a week. A section called “Khush Khat” (“Happy Letters”), a feature that allowed readers to exchange correspondence and set up meetings with one another, was wildly popular; the magazine’s editors understood that many gay Indians couldn’t risk receiving such letters at home at a time when coming out was, for many, still unthinkable.

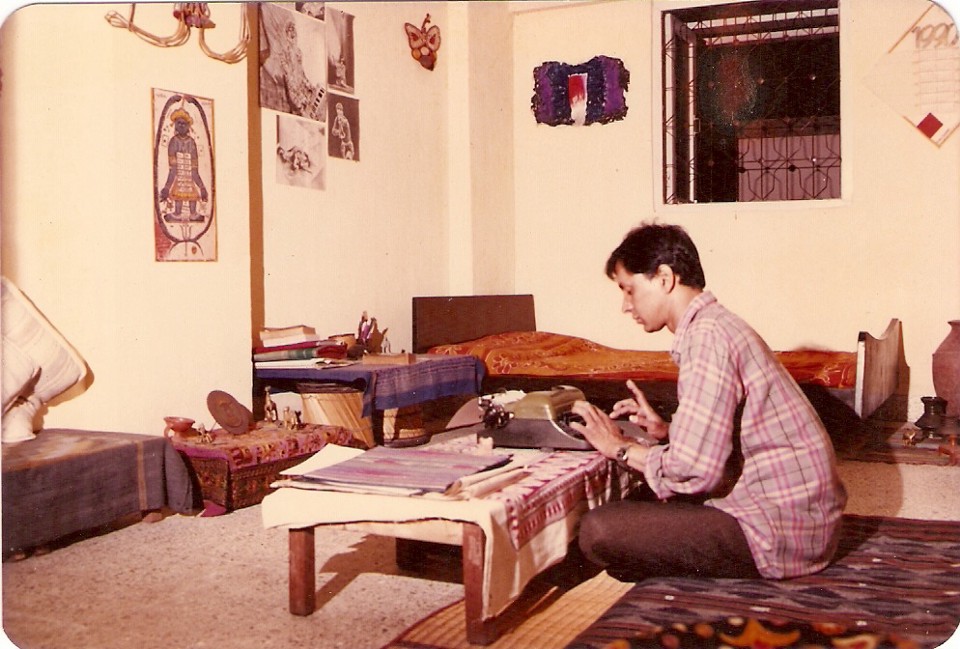

Sridhar Rangayan works on Bombay Dost in its early days. (Photo: Sridhar Rangayan)

“It was like a Cupid in many ways,” Sridhar Rangayan, 54, a filmmaker and founder of KASHISH , the Mumbai International Queer Film Festival, who also edited several early issues, says. He laughs: “And a courier boy.”

Rendezvous between letter-senders took months to come to fruition given the time lag between each issue, according to Rangayan. “It was very popular because people wanted to make a connection somehow,” he says.

Through health-centric features, the magazine addressed emotional and mental wellness in the community. “Papa Passion,” one early series, was the magazine’s version of an “Agony Aunt” column. Questions ranged from “If I masturbate will I die?” to “How should I come out to my parents?” Through an answering machine number where readers could leave messages, the founders arranged meetings at public locations for sexual distress and identity-related counseling.

Distribution was a tricky matter in those days: How could the lay reader discretely access such a taboo publication? A couple of vendors in the city stocked the magazine and stuffed it behind other titles, producing Bombay Dost only when buyers explicitly sought it. “The vendor would disappear and then come back with a brown paper envelope,” Rangayan says. “Then the buyer would put it in his bag and run. It is comical now, but it was anxiety-inducing then.” A single magazine might have gone through 100 pairs of hands, Rangayan estimates. They were traded between people or left on canteen tables and office floors, according to Kavi.

Distribution was a tricky matter in those days: How could the lay reader discretely access such a taboo publication?

In 1994, the editors formed a non-profit group called the Humsafar Trust, which, among other services, offered face-to-face counseling. “There were so many things we couldn’t cater to through the newsletter,” Abbasi says. “We had to have a separate outfit.” (Full disclosure: Last year the trust offered a three-month media fellowship to report on queer issues that this reporter participated in.)

At some point in the early aughts — the founders say it was a gradual process — the enterprise became unsustainabledue to time constraints for its volunteer staff, dwindling funds, and lack of advertising opportunities. It shuttered in 2002. “We didn’t intend to kill the magazine, it died a natural death because we just couldn’t manage,” Abbasi says. It seemed like an era had ended.

That same decade, life began to improve for gay people in India. In December 2001, the non-profit group Naz Foundation filed a petition with the Delhi High Court to challenge Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, a British-era provision outlawing sexual acts considered “against the order of nature” — which effectively criminalized the gay community.

As the petition moved through the legal system, the new millennium brought with it fuzzy dial-up connections that offered access to anonymous chatrooms, email, and other possibilities to speak to other gay men that hadn’t existed before the dot-com boom.

In April 2009, the men behind Bombay Dost felt impelled to print again. That year, the group posted a teaser on Facebook promising 56 full-color pages, a glossy cover, and a memorable comeback. “India’s first LGBT magazine is returning in a new, bolder-than-ever avatar,” the post said. “The boldness has to do with the forthrightness with which LGBT cultural expression is showcased.”

The 2016 edition, featuring Bollywood actor Manoj Majpayee. (Photo: QGraphy)

Indeed, there couldn’t have been a better moment for the relaunch. In July 2009, in a widely hailed judgment, the Delhi High Court read down part of Section 377, thus effectively decriminalizing consensual same-sex acts. (That judgment was later overturned by a 2013 Supreme Court decision; a curative petition is still pending.)

Since then, the magazine has been coming out once or twice a year, and continues to be a volunteer effort facing some of the same challenges as before, including time constraints, budget, and logistics. And a new one: the Internet. With new competition from digital content targeted at the gay reader in India, the Bombay Dost team is now working on taking the magazine online. “The mandate has changed subtly,” Kavi says. “It is a mutating animal depending on the environment.”

So what value, then, does the print magazine still have? As queer issues have found a space in mainstream publications, Bombay Dost has expanded its coverage and audience with a new look. “It is now much glossier, has a more mainstream look, and is a little bit more like a lifestyle magazine,” Rangayan says. “It was more radical and political in the earlier years; now the cover stories are more film- and celebrity-focused.” Aside from Bajpayee, the actress Kalki Koechlin and the celebrity chef Vikas Khanna have also appeared on the cover in the last five years.

About 1,000 copies are printed each time, and some of the awkwardness about buying such a magazine discretely have dissipated, with shops openly selling it for Rs 150 ($2). A grant from the United Nations Development Programme has helped the magazine financially in its second outing.

Ruth Vanita, a liberal and South and Southeast Asian studies professor at the University of Montana, writes in an email that the print format’s discreetness and accessibility remains crucial for the gay community. Not everyone has regular access to the Internet, she notes, and young people living at home may prefer hiding a magazine to their browsing history. “There are still huge numbers of people struggling with homophobia, who find it extremely difficult to live openly and freely,” she writes. “Even those who are living openly face daily discrimination. So it helps a great deal to have a magazine like Bombay Dost, which not only chronicles problems but also celebrates achievements and the joys of being LGBT.”

The magazine retains many fans who remember how Bombay Dost built a sense of community in an alienating time too. “It is difficult to estimate the value of that kind of work,” Pawan Dhall, a Kolkata-based queer activist and researcher who started his own LGBT publication shortly after Bombay Dost’s launch in 1990, says. “It was the first beacon of hope for disconnected, isolated people.”

Dhall’s publication, Pravatrak, stopped printing in 2000; he launched another publication, Varta, in August 2013. Other older gay-centric publications have ceased publications altogether, or then gone completely online;Dhall says he has the complete set of Bombay Dosts archived, whose value he sees now as both academic and nostalgic. That nostalgic value is in itself a powerful motivation for the founders to keep it going. “Bombay Dost is a dream that its editors have tried to keep alive,” Rangayan says. “It has historical value.”