On Monday, Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds (R) signed into law a bill allowing the Iowa Farm Bureau to sell “health benefit plans” that would not be regulated by the state’s Insurance Division and would not be required to comply with any of the Affordable Care Act‘s regulations, including those governing essential health benefits and coverage for people with pre-existing conditions. The legislation, which is similar to a system in Tennessee and which experts believe is more likely to hold up in court than Idaho’s recent regulatory moves, circumvents the ACA’s regulations by declaring that the plans “shall be deemed not to be insurance.”

Iowa likely won’t be the only state to pass such a law. Prior to the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in December, purchasers of such plans would have been subject to the ACA’s individual mandate penalty imposed on individuals who don’t purchase health insurance. The TCJA repealed that mandate, however, which means people who buy a health benefit plan through the Iowa Farm Bureau now won’t have to pay any kind of penalty.

“If the ACA’s insurance rules can’t be repealed, then an alternative is to get people the option of escaping them,” the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Larry Levitt told the Washington Post. “Without the penalty, the door is wide open for plans like this.”

The debate over the likely effects of this legislation echoes pretty much every other debate over both previous GOP efforts to repeal the ACA and current federal and state-level GOP efforts to loosen the ACA’s regulations. Opponents argue that the Iowa bill will drive up health insurance premiums for sicker consumers and lead to skimpy coverage that fails people when they need it most. Proponents, meanwhile, argue it will increase the number of low-cost choices for certain Iowa residents (namely, healthy residents who don’t need comprehensive coverage).

“Iowa’s individual insurance market has collapsed because of Obamacare,” a spokesperson for Reynolds told Politico. “There are farmers and small-business owners across Iowa who can’t afford insurance.”

Implicit in the argument advanced by fans of laws such as Iowa’s is usually a promise that a given law or regulatory change can deliver better health insurance at a lower cost. But the simple truth about health insurance that’s useful to keep in mind when evaluating any of these proposals is that, generally speaking, you get what you pay for.

Narrow-network plans, for example, often offer lower premiums, but people get less choice about the providers they see. High-deductible plans also offer lower premiums, but consumers face higher out-of-pocket costs before they hit that deductible. Similarly, people who buy these new farm bureau plans in Iowa will pay less for their coverage, but they will also get less comprehensive coverage. Before the ACA mandated coverage of the 10 essential health benefits, it was fairly typical for plans in the non-group market to not include coverage of things like maternity care, or mental-health services, or treatment for substance use disorders, or specialty drugs; the Iowa plans will likely include similar restrictions, and may also subject consumers to annual coverage limits.

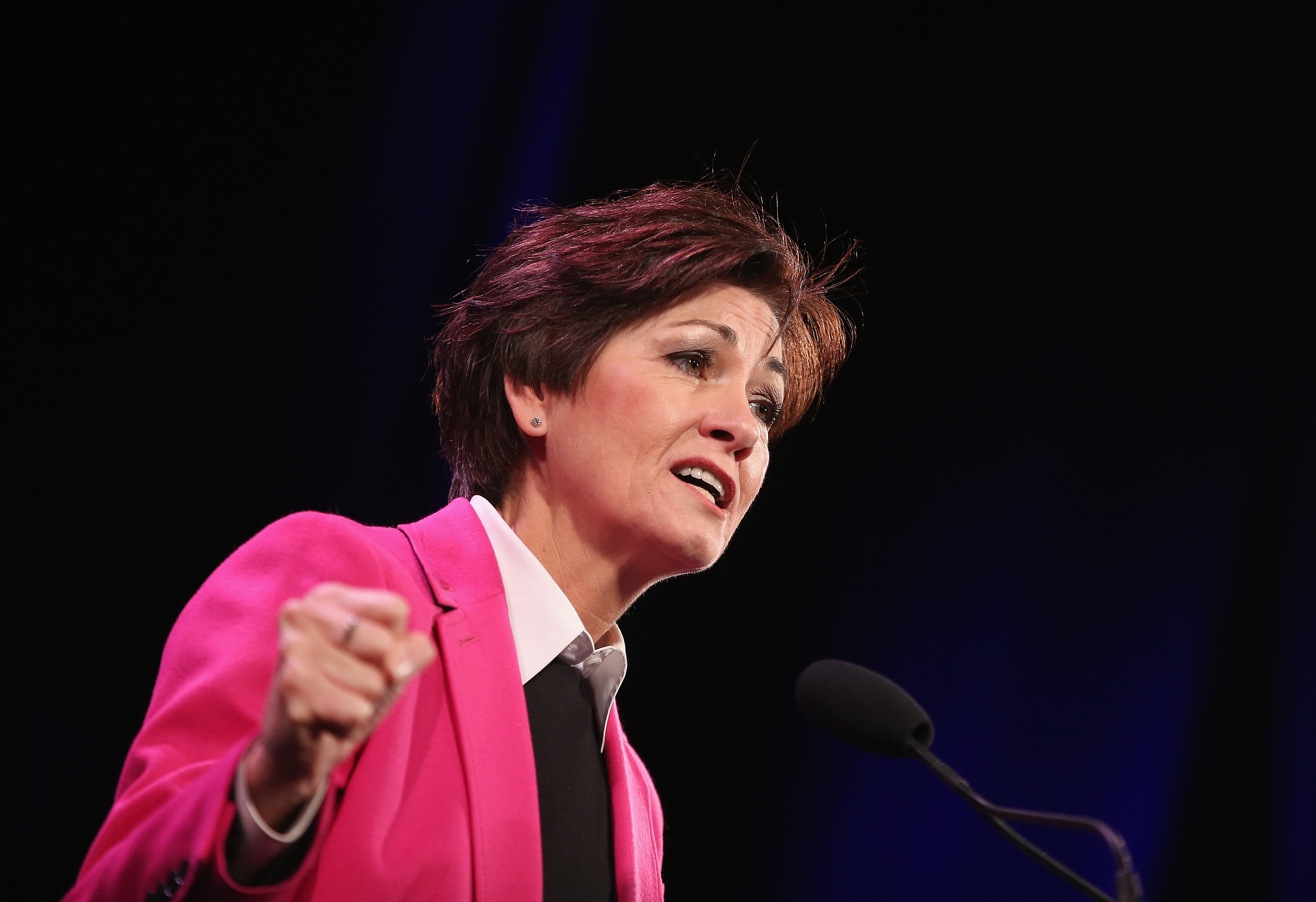

(Photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images)

For healthy people, sacrificing some of the comprehensiveness of their coverage in exchange for lower premiums may indeed represent an attractive tradeoff—it’s not crazy for a healthy 25-year-old male, for example, to question why they should have to pay so much for a plan that covers maternity care or mental-health treatment that they don’t currently need.

But conversations around this dilemma shouldn’t ignore the fact that there is a meaningful tradeoff involved in purchasing such skimpy plans. That healthy 25-year-old male may not need mental-health treatment today, but what happens if he hurts his back at work, gets addicted to opioids, and ultimately requires treatment for a substance use disorder? Or gets in a car accident and spends weeks in the hospital, exceeding his annual coverage limit? Or is diagnosed with a rare form of cancer that requires a specialty chemotherapy drug treatment regimen not covered by insurance? The purchaser of such a plan may never have a need for the coverage they’re giving up so they may never notice what they’re sacrificing, but they are nonetheless still “getting” less (in the form of reduced security).

This “you get what you pay for” maxim applies in a larger sense as well. A healthy consumer purchasing ACA-compliant insurance in the non-group market may not themselves need all of the law’s protections for those with pre-existing conditions today, but they might need them the next year, or the year after that, or five years after that. In exchange for their premiums, which subsidize people with pre-existing conditions and serious medical issues, the healthy consumer is paying for the assurance that they’ll be able to find comprehensive health insurance if they themselves are ever diagnosed with a serious health condition down the road.

Concerns over premiums and the stability of the non-group markets, particularly in places like Iowa and Tennessee, are well-placed. And there are plenty of important and legitimate philosophical and ideological debates over how best to improve the affordability of health insurance and health care in this country. These debates, however, should acknowledge the fact that the health insurance market is still subject to the usual laws of economics, and there’s no magical solution to the problem of rising premiums that doesn’t also involve some painful tradeoffs.