For at least the past decade, it has been widely assumed that Americans overwhelmingly identify as either a member of the political left or right. When it comes time to vote, even self-proclaimed independents consistently come down on one side or the other.

A large bipartisan study suggests this binary framework, however useful in predicting election outcomes, greatly oversimplifies the relationship Americans have with their nation’s politics and government.

Hidden Tribes, a report by the initiative More in Common, confirms we are experiencing a time of deep polarization, rooted in very different value systems. But it further finds “the middle is far larger than conventional wisdom suggests, and the strident wings of progressivism and conservatism far smaller.”

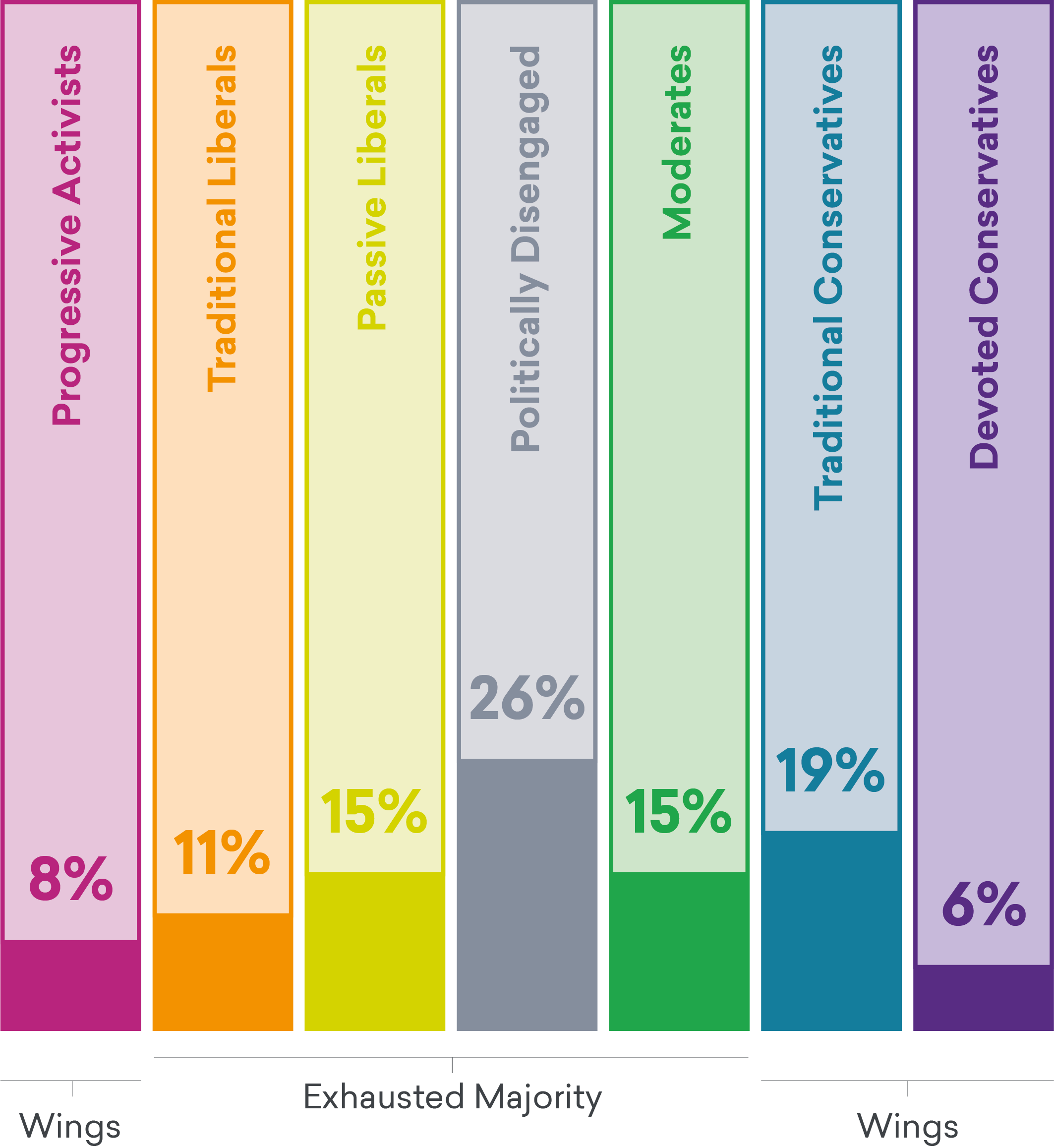

It argues Americans are best divided into seven distinct tribes: progressive activists (about 8 percent of the population), traditional liberals (11 percent), passive liberals (15 percent), the politically disengaged (26 percent), moderates (15 percent), traditional conservatives (19 percent), and devoted conservatives (6 percent).

While most of those are self-defining, a couple cry out for clarification. “Passive liberals” are defined as people who are largely uninformed and politics-averse, “but when pushed, they have a modern outlook and tend to have liberal views on social issues.” They are the people Democrats try, and often fail, to get to the polls.

The distinction between “traditional” and “devoted” conservatives is mainly one of vehemence. Traditional conservatives “have a clear sense of identity as American, Christian, and conservative, but they are not as strident in their beliefs as devoted conservatives,” the report reads.

Nevertheless, the study’s authors identify both types of conservatives, along with progressive activists, as the “wings” of our political structure. Members of these groups, which combined make up one-third of the nation, are true believers in their cause, and are more likely than most to be politically engaged.

Members of the other four groups—including traditional liberals, defined as people with “strong humanitarian values” who “respond best to rational argument”—make up what the authors call the “exhausted majority.” For all their differences, people in this category—who make up 67 percent of the population—are more ideologically flexible, fatigued by all the polarization and angry rhetoric, and generally supportive of political compromise.

They also tend to feel forgotten, for obvious reasons.

To get a better idea of the findings and what they mean for the coming election and beyond, Pacific Standard interviewed lead author Stephen Hawkins, a public opinion researcher who earned a master’s degree from Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. He joined More in Common soon after its founding in 2016, and conducted similar research in several European nations before turning to his home country.

Your basic conclusion is that the red-blue divide is exaggerated and misleading. Most Americans are not committed liberals or conservatives, but are rather part of what you label the “exhausted majority.” Why that label?

The reason we decided to call it the “exhausted majority” was because they expressed frustration with America’s division, and felt they were forgotten by the media. They’re frustrated by the animosity in this country, but they do have party orientations. “Traditional liberals,” which we include in this group, are reliable Democrats; “passive liberals,” if they vote, probably vote for Democrats. Moderates are pretty evenly split, and the politically disengaged don’t vote very much.

What brings them together isn’t so much confusion over their partisan orientation, although that might be true of moderates and the disengaged. What unites that 67 percent of the population is frustration at the increased division in our country, and a desire for a change in our public discourse.

That’s certainly understandable. But no politician’s discourse in many decades has been cruder than that of Donald Trump, and a lot of these people voted for him. Why?

What members of the exhausted majority who voted for Trump might tell you is they felt frustrated by what they see as a kind of policing of speech—a narrowing of views that are acceptable, and a growing intolerance toward people with traditional, conservative, Christian world views. They felt the country was sliding away from accepting their culture, and they were increasingly being judged for their word choices in a way that felt unfair to them.

I did in-depth interviews and focus groups as well as the quantitative work, so let me give you an example. I was talking to a woman who was living in a trailer in Louisiana. She was living on a meager income with her daughter and her daughter’s son. I don’t think she had running water in her trailer.

(Photo: More in Common)

She said the biggest problems facing America were poverty and hunger. But over the time I spoke with her, which was more than an hour, she was most riled up when she said: “I’m a straightforward person. I just like to say it as I see it.” She complained that “you can’t say what you think any more.” I thought, this woman is facing every conceivable socioeconomic problem, but the thing that really bothers her is that people are judging her because she doesn’t know the correct terminology around gender and sex. She felt she was being judged as intolerant for being candid and speaking her mind.

Where is she getting this? There is a segment of the left that takes identity concerns to an absurd level, but it is hardly representative of political liberals. Is she being fed this by conservative media?

It’s a good question I can’t answer. But I can say those feelings were directly connected with her feelings about Trump. She said, “Sometimes he’s wrong, and sometimes he runs his mouth, but at least he says what he thinks.”

You identify this as an area where progressives are out of touch with a large majority of the country. People on the left either support this sort of political correctness or find it a minor irritant, but others see it as a strong negative.

We asked people whether they felt free to speak their minds on issues like Islam, immigration, sexuality, and racism. In every case, between half and two-thirds of Americans felt there was pressure to think a certain way about the issue. It was something that came up in interviews as well. Even some liberals complained that the language [surrounding identity] keeps changing, and there are repercussions for getting it wrong. These aren’t people who want to demean others, but they feel people are too sensitive about these issues.

That’s a bit rich, given the insensitive way racial and sexual minorities have been treated historically. But it brings up a pattern I noticed regarding the “exhausted majority”: Many give what seem to be confused or contradictory responses. For instance, 82 percent agreed racism is at least a somewhat serious problem, but they are evenly divided on whether white privilege exists. Isn’t that asking the same question two ways, and getting two different answers?

No, I don’t think so. You can agree that racism is a problem while disagreeing on its scope and its solution. I think we’re seeing that here. Four out of five people agree racism is a problem. But when you ask their opinion of the statement, “One symptom of this problem is that police are disproportionately likely to kill black men,” you lose a lot of people. Conservatives will say, “It’s not race; it’s due to their culture.” Then if you ask about Black Lives Matter, you lose still more people. People associate the movement with the riots that took place in Baltimore and Ferguson.

Similarly, you find a big majority believes sexism is a problem, but they don’t especially like people who are trying to combat it. How much of this is just being conflict averse—feeling uncomfortable with the discord that a fight for justice inevitably entails?

Moderates are more conflict-averse than the other groups are. In focus groups of moderates, people are quiet and speak for shorter amounts of time. But that’s only part of the issue. A large plurality of women think feminists “just attack men.” They see there are instances when women are treated worse than men, but they don’t necessarily see “mansplaining” or “slut-shaming” as a problem.

This was a one-time snapshot, but do you have any indication whether membership in these categories is static, or does it shift? I suspect Trump has inspired radicalization on both sides.

We found only 36 percent of Americans said their political orientation has stayed the same over their lifetimes. So two-thirds report some movement. It’s likely we’ll do a follow-up study after the mid-terms, asking a lot of people who took the original survey 10 or 11 months ago. We’ll see whether people have shifted.

Prominent political scientist Francis Fukuyama complains that we do a terrible job educating our children about civics. How knowledgeable did you find the public to be about how the government works?

Well, a non-trivial percentage of the country couldn’t name the vice president, or tell us which branch of the government can deem a bill to be unconstitutional. That’s not encouraging. But I don’t know the degree to which that’s a causal factor in today’s politics, as opposed to tribal loyalties, and the disengagement of one-quarter of Americans.

Where do we go from here? Does this data give you any hope that there may be a way to bridge some of these divides, or at least restore some civility to our politics?

Almost eight out of 10 Americans think our differences aren’t so big that we can’t work together. There’s still a sense that we have a capacity to collaborate. Among the exhausted majority, people are more likely to say “I want my side to listen. I’m willing to compromise.”

OK, but that’s asymmetrical. There’s a lot of research that shows conservatives are far less open to compromise than liberals.

It’s true that the left is more willing to compromise than the right. But those in the center are also more willing to compromise than those on the wings.

My suspicion is the current polarization won’t begin to wane until prominent politicians start to see that appealing to our better natures benefits them.

There’s not a lot of incentive for that at the moment. There needs to be less reward for outrage and insisting on dogmatic consistency. We need to be willing to engage in thoughtful conversations.

A major finding of our study is people have very different world views, which start with how we view human nature. These create distinctive cultures, and they need to be understood as such, rather than seeing people as members of the “good team” or the “bad team.”

What happened to Team America?

It would help if we could restore a sense of national identity. In the Cold War, there was a strong sense that being an American meant something. It referred to a set of ideas, principles, and values. That brought people together, especially when you had an enemy that opposed those values.

Today, the younger generation is less excited and proud about being Americans. The underlying ideas that unite Americans are growing fewer and fewer. It’s going to take a strong set of leaders to push us in a new direction.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.