Once again, Hillary Clinton is offering some opinions, and, once again, she is being told to keep quiet. This is a familiar pattern for us, no less for her, so perhaps it shouldn’t be so surprising to see it recur. But I’d like to push back a bit on this one.

The occasion for this current dust-up is, of course, the release of Clinton’s new book What Happened. Disclosure: I haven’t read it. (Honestly, I don’t find many candidate narratives of their own campaigns all that interesting.) Nor have many of those who are currently criticizing her for writing it. But the main criticisms seem to be:

- Clinton shouldn’t be criticizing Bernie Sanders right now because that’s just causing Democratic divisions at a time when the party need unity.

- She lost to a vulnerable candidate and thus must be an even worse candidate herself.

- Her general election loss means it’s time for her to go away and stop “consuming oxygen.”

I’d like to address each of these in turn.

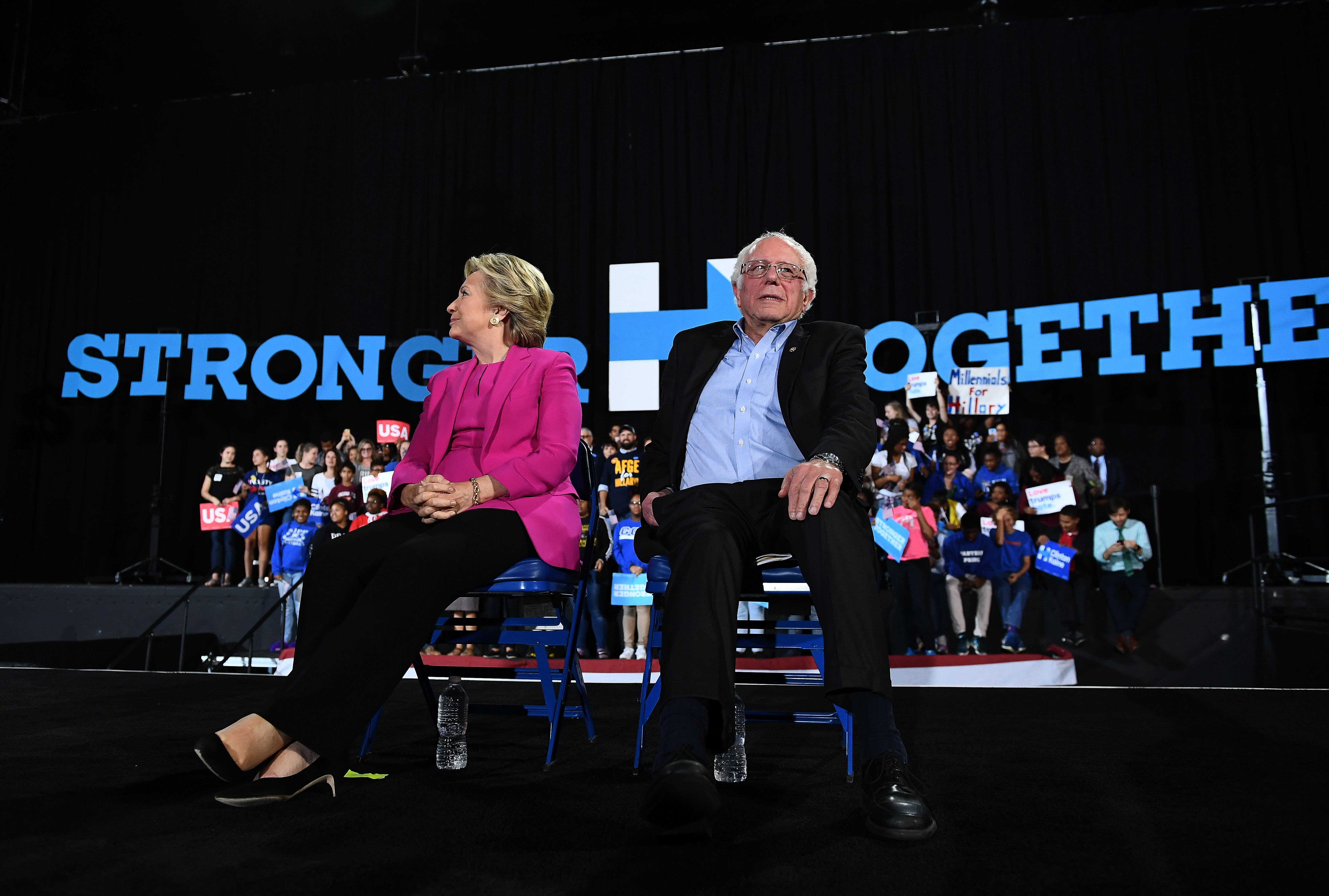

The demands of the Sanders faction of the Democratic Party have struck me as unusual. Sanders ran an impressive campaign for the 2016 nomination, winning far more votes and delegates than many observers had expected given Clinton’s broad level of support among party leaders. Nonetheless, he came up short in that contest. Clinton won the nomination, and Sanders endorsed her at the convention.

But Sanders and his supporters have continued to use his better-than-expected run to claim some sort of mandate to change the structure of the Democratic Party and the way it nominates candidates for high office, whether that means more open primaries, more caucuses, or neutered superdelegates. And Sanders is doing all the things a candidate for 2020 would be doing at this point.

(Photo: Simon & Schuster)

This is to say, there is a lively debate within the Democratic Party right now over the best direction to head, and those divisions largely break down along the Clinton/Sanders lines from 2016. It’s not at all clear why one of those candidates and his supporters should be encouraged to participate in that debate while the other—the one who won the nomination—should disappear.

Does her book add fuel to intra-party fights? Undoubtedly. And there’s a great time for a party to try to squelch dissent within its ranks. That’s in the few months leading up to a general election. We’re nowhere near there. We’re more than a year from the congressional mid-term elections and more than three years from the next presidential general election. Now is precisely when a party argues over its differences. If you don’t think now is the time for Democrats to debate how their party runs and what it should stand for, then you basically think there’s never such a time.

Now, a lot of the arguments across Sanders and Clinton factional lines stem from their supporters’ feelings about point No. 2 above—her performance relative to Donald Trump last year. Many Sanders supporters (and others) feel that Clinton should have done better against Trump, and her narrow loss suggests that a different Democratic candidate would be president today.

I addressed much of this in a post last year, but to briefly summarize: Clinton out-campaigned Trump in pretty much every way, from debate performances to advertising to ground game to fundraising to candidate travel. That is, in terms of the things candidates do, given the aspects of the political world over which they have control and the information that they had prior to the election, Clinton was a dramatically better candidate. To say she was a bad candidate because she lost is simply not a very useful claim. One can be a very good candidate, even a perfect one, and still lose an election.

Clinton was trying to do something that is historically very challenging: win a third consecutive White House term for a party during a period of modest economic growth. The “fundamentals” suggested a narrow Republican victory; Clinton modestly out-performed those fundamentals.

Now, one’s view of how Clinton should have performed depends strongly on the standard to which she is being held. If you’re saying she under-performed, are you comparing her to:

- How a typical Democrat would do against a typical Republican in similar fundamental conditions?

- How you think she should have done given that she was running against an undisciplined and toxic Republican nominee?

- How you think Sanders, Joe Biden, or some other Democrat would have done in a similar race?

I would note that the first of these is the only one for which we have any real evidence; the other options are basically hunches. And the evidence suggests that, despite Trump’s obvious problems as a campaigner and the fact that he went out of his way to offend key constituencies, party lines held. Roughly 90 percent of Republicans voted for Trump, and roughly the same percentage of Democrats voted for Clinton.

She’s being held to an odd double-standard of campaigning here if all of her flaws as a candidate were fatal while none of Trump’s were. She should have campaigned in Wisconsin? Sure. He bragged on tape about committing sexual assault. She could have given a better convention speech? Fine. He publicly attacked a Gold Star family and threatened to jail his opponent upon his victory. For every run-of-the-mill problem in her campaign, he committed some sort of epic apostasy that’s supposed to end careers and possibly result in prison time. And the election results ended up very close to what the economic forecast models predicted. Maybe, just maybe, in a highly partisan system, individual candidate activities just don’t matter all that much.

(Photo: Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images)

Now, on the question of whether it’s time for Clinton to go away, I would refer you to John Anderson’s wonderful post from last week. As he notes, the orders to go away seem historically unusual:

It’s kind of funny how nobody cares how John Kerry acted after he lost the “easily winnable election” in 2004 and instead of going to live as a monk on an island in the Black Sea and contemplate his sins did this. Just like it’s also funny nobody cares that John Edwards went back to practicing law. And funny that Richard M. Nixon, one of the most destructive American politicians of the 20th century, wrote books too.

In general, our political culture is pretty tough on failed presidential candidates. Walter Mondale, Mitt Romney, and Kerry will pretty much always be labeled losers even if they ran pretty good campaigns and performed about where we should have expected them to perform. But the derision aimed at Clinton is atypical. Surely the first female major party nominee and the popular winner in the biggest popular vote/Electoral College mismatch in history has something to say.

My advice, if anyone’s interested, is that if you’re not particularly interested in her take on politics, don’t buy or read Clinton’s book, and leave it at that. And if you’re a prominent figure in a party that wishes to be seen as a champion of professional women, think twice before silencing one.