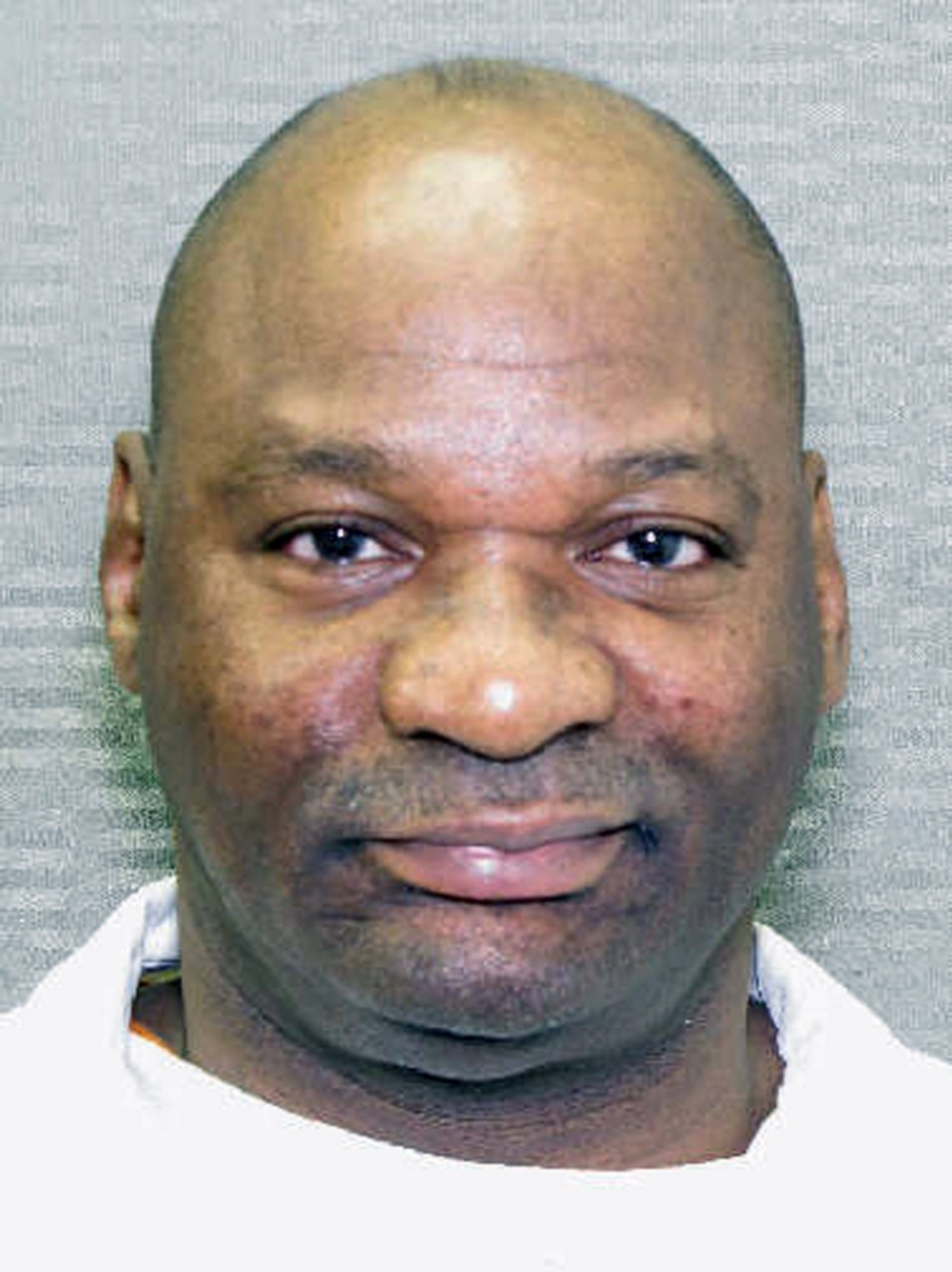

The state of Texas really wants to kill Bobby J. Moore. The Supreme Court, in its 5–3 decision in Moore v Texas on Tuesday, says it can’t. Better still, the majority and the three dissenters all agree, Texas has to stop comparing potentially intellectually disabled individuals to the fictional character Lennie, from John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, when making decisions about life and death.

In 1980, Moore, a black man with a variety of disabilities, shot a 72-year-old store clerk in Houston. He was sentenced to death soon after, but his long journey through the legal system has seen many changes in how we adjudicate such cases. In 2002, the Supreme Court ruled in Atkins v. Virginia that people with intellectual disabilities should not be executed, but the ruling left it up to the states to determine who, precisely, qualifies as intellectually disabled.

When courts adjudicate who is or is not really disabled, injustice and bias always creep in.

Enter “the Lennie standard.” In 2004, a justice in Texas’ Court of Criminal Appeals suggested that “Most Texas citizens might agree that Steinbeck’s Lennie should, by virtue of his lack of reasoning ability and adaptive skills, be exempt” from the death penalty. Therefore, instead of basing decisions on either the foremost medical standards or the best practices of the psychiatric community — let alone on the expertise of the disability rights world — Texas courts suggested performing an act of literary analysis on a given individual to determine whether the state could kill them. As Brian Stull, senior staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union, tells me: “Numerous people have been executed in Texas because courts found they were not intellectually disabled under this standard, including ACLU client Robert Ladd and Marvin Wilson.” Moore, whom the CCA had found to be more functional than the Lennie standard, was slated to be next.

But the Supreme Court disagrees. Tuesday’s majority decision, authored by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, clearly swept away Ex Parte Briseno, the legal opinion that established the Lennie standard, but so did the dissent, authored by Chief Justice John Roberts. It’s clear that “Justice Roberts found the Lennie standard ridiculous,” says Samantha Crane, a lawyer and director of public policy for the Autistic Self Advocacy Network. Ginsburg, Crane explained, wanted to rely on medical expertise, whereas Roberts wanted to give courts more “discretion in terms of which people with intellectual disabilities should be protected from execution.”

So how should we assess intellectual disability? Here, the Supreme Court, and courts in general, are divided. IQ tests have long been used to draw bright dividing lines between intellectually disabled, normal, and genius. They are, of course, now widely discredited as distorted by all types of bias.

Moore took seven IQ tests over the years, with results more or less coalescing in the 70s (70 is the standard for intellectual disability), and the legal proceedings hinged on whether his range was 69–74 or 70–75. Other judges and courts, including the Texas CCA in its hearings on Moore, tried to determine whether an individual could be considered to have an intellectual disability based on how well they adapted to circumstances. The CCA, for example, cited Moore’s good behavior in prison, his survival while homeless, and the income he made mowing lawns as evidence that he wasn’t disabled enough to live.

Ginsburg and the majority argued otherwise. As Stull tells me: “The detailed decision dismantles many of the non-medical and non-scientific tests which courts, including but not limited to the CCA, have contrived to deny Atkins protection.” (Atkins is the 2002 decision that ruled it unconstitutional to execute people who have intellectual disabilities, but which states like Texas have tried to undermine.) Stull continues: “Some of those improper tests have relied on stereotypes regarding intellectual disability while others have involved fundamental misunderstandings. One of the most troubling myths about the condition today’s decision knocks down is that people with intellectual disability cannot have any strengths.” In other words, Ginsburg cited the definitions used by the medical community that acknowledge a person can be, at once, intellectually disabled and yet able to adapt to one’s circumstances.

But there’s still the limitation that Moore v. Texas only expands protections for people with intellectual disabilities. Crane is worried that courts will try to use histories of trauma, evidence of developmental disabilities, and other forms of neurodiverse behavior as ways of linking violent behavior to some other kind of disability, and thus skirt precedent.

“Until we see a broader death penalty exemption — one that includes people with other kinds of disabilities that affect adaptive functioning — we’re going to keep seeing courts making the same kinds of awful arguments in favor of executing people with intellectual disability,” Crane says. “They’ll continue to argue that the ‘real’ cause of adaptive functioning issues is mental illness or developmental disability, so they’re not covered by Atkins.”

When courts adjudicate who is or is not really disabled, injustice and bias always creep in. Disability operates on spectrums; diagnoses intersect, magnify, or even conceal each other. No human being perfectly fits any one set of criteria. The Ginsburg standard of embracing the best medical knowledge is a vast improvement over performing amateur literary criticism while determining whom to execute, but it’s far from just.

Meanwhile, Bobby J. Moore is currently still on death row, waiting to be re-evaluated and moved to a new prison.