When parents go to prison, it’s the children who pay.

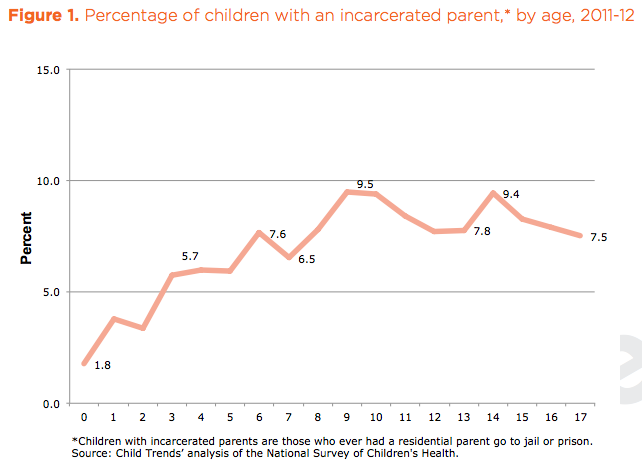

That’s the conclusion of a new report from Child Trends, a non-profit center dedicated to providing educational research for lawmakers. The center’s new report on Parents Behind Bars examines the impact of incarceration on the children of inmates, and the results aren’t pretty: More than five million children in the United States—one in 14, to be more precise—had at least one parent in prison at some point in their lives, and the resulting trauma can often lead to both physical and psychological problems for their entire lives.

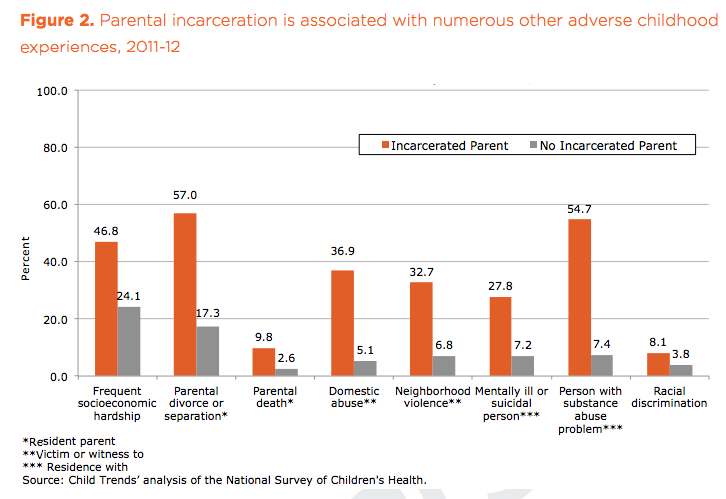

The causes of this trauma are varied, but in all cases the incarceration means a child is far more likely to experience additional adversity in the crucial years of their development. More than half of children who have seen a parent go to prison have also lived with someone with a substance abuse problem (compared to less than 10 percent of those without a parent in prison). Nearly 60 percent also saw their parents divorce, while the divorce rate was substantially lower for those families without prison in the mix. Finally, more than a third witnessed domestic violence. Incarceration, the forcible wrenching of a family unit, leaves dysfunction in its wake.

These traumas have serious long-term consequences for childhood development. According to Child Trends, children between the ages of six and 11 with incarcerated parents are more likely to have problems at school and be less engaged in their classes. They’re also more likely than other children to have emotional control issues (72 percent versus 64 percent). Part of this is simply due to stigma: “Having an imprisoned parent is an example of a loss that is not socially approved or (often) supported,” the report states, “which may compound children’s grief and pain, leading to emotional difficulties and problem behaviors.”

In many cases, family trauma starts—and ends—with the tendrils of the prison-industrial complex. It’s unclear from the Child Trends data if this is correlational or some level of causation, but longitudinal research on the relationship between socioeconomic status and dysfunctional family structures shows the two are certainly intermingled. Consider that 20 percent of the 2.2 million inmates in the U.S. have child support obligations, many of which can’t be met while prisoners work for pennies behind bars. The result is that lower-income single-parent households are perpetually stuck in poverty (45 percent of children without fathers, either in jail or otherwise, are living in poverty), and are naturally predisposed to traumas like domestic violence and mental illness.

It’s black children who disproportionately endure the carceral trauma of the prison-industrial complex. Less-educated black men have made up the bulk of the U.S. prison explosion since the 1980s, jumping from 10 percent in 1980 to 30 percent in 2000. The Child Trends data confirms this damaging effect on the children they leave behind: The children of parents with no high school education are 41 percent more likely to have one in prison. It’s a vicious cycle of destitution and despair, and it can swallow successive generations of children whole.

So what can be done to remedy this corrosive disconnect between inmates and their children? Child Trends recommends that policymakers “make it easier for children to maintain positive relationships with their parents” during incarceration, noting that 52 percent of incarcerated parents “had at least monthly mail contact” with their children, while 38 percent “had at least monthly phone contact.” Reducing the absurd cost of prison phone calls certainly helps, as does putting the administrative purview of visitation rights under state control, as opposed to individual private prison organizations (although Child Trends does note that in-person visits can be more upsetting to children.)

But the real answer, obviously, is to put an end to mass incarceration once and for all: Get rid of mandatory minimums for non-violent drug offenses; grant commutations to those already behind bars; overhaul the bail system that keeps police coffers full while permanently tarring people’s lives over minor infractions; reign in overzealous prosecutors; eliminate racism from every corner of the criminal justice system. But given how tough the legislative road ahead for criminal justice amendment looks in Congress, the small programs and reforms cited by the Child Trends report might have to be enough—for now.