Math students everywhere will be eating pies in class this week in celebration of what is known as Pi Day, the 14th day of the third month.

The symbol π (pronounced paɪ in English) is the 16th letter of the Greek alphabet and is used in mathematics to stand for a real number of special significance. When π is written in decimal notation, it begins 3.14, suggesting the date 3/14. In fact, the decimal expansion of π begins 3.1415, so Pi Day 2015, whose date was abbreviated as 3/14/15, was said to be of special significance, a once-per-century coincidence. (The same was said about the following year, on 3/14/16, since 3.1416 is a closer approximation to π than is 3.1415.)

Besides a reason to enjoy baked goods while feeling mathematically in-the-know, just what is π anyway?

It’s defined to be the ratio between the circumference of a circle and the diameter of that circle. This ratio is the same for any size circle, so it’s intrinsically attached to the idea of circularity. The circle is a fundamental shape, so it’s natural to wonder about this fundamental ratio. People have been doing so going back at least to the ancient Babylonians.

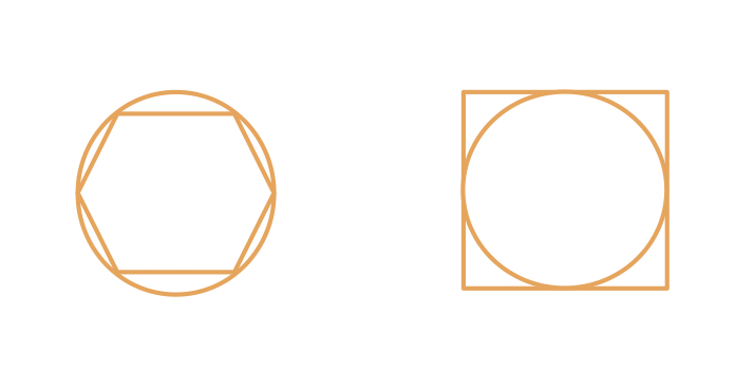

You can see that π is greater than three if you look at a hexagon inscribed within a circle. The perimeter of the hexagon is shorter than the circumference of the circle, and yet the ratio of the hexagon’s perimeter to the circle’s diameter is three. And you can see that π is less than four if you look at the square that circumscribes a circle. The square’s perimeter is longer than the circle’s circumference, and yet the ratio of this perimeter to the diameter of the circle is four. So π is somewhere in there between three and four. OK, but what number is it?

A little experimentation with a measuring tape and a dinner plate suggests that π might be 22/7, a number whose decimal expansion begins 3.14. But it turns out that 22/7 is approximately 3.1429, while even 2,250 years ago Archimedes knew that π is approximately 3.1416. The fraction 355/113 is much closer to π but still not exactly equal to it.

Fractionally Closer?

So this raises the question: Is there some other fraction out there that equals π, not merely approximately but exactly? The answer is no. In 1761, Swiss mathematician Johann Lambert proved that no fraction exactly equals π. This implies that its decimal expansion is never-ending, with no repeated pattern.

The German mathematician Ferdinand Lindemann proved in 1882 that π is, in fact, transcendental, which means that it does not solve any polynomial equation with integer coefficients. This implies in some sense that there isn’t ever going to be a simple way of describing π arithmetically. Nowadays, machines can compute trillions of decimal digits of π, but that in no way helps us understand what π is exactly. It’s easiest just to say that, to be exact, π is equal to … π.

No one knows whether each of the 10 digits—zero through nine—appears with equal frequency in the decimal expansion of π, as we would expect if the digits of π were produced by a random digit generator. This illustrates that a strikingly elementary question can be out of reach of modern mathematics. Perhaps in a century mankind will know the answer to this question, but it’s not even clear at this time how to attack it effectively.

Everything’s Coming Up π

What is astonishing about π is that it appears in many different mathematical contexts and across all mathematical areas. It turns out that π is the ratio of the area of a circle to the area of the square built on the radius of the circle. That seems like a coincidence, because π was defined to be a different ratio. But the two ratios are the same. π is also the ratio of the surface area of a sphere to the area of the square built on the diameter of the square. And what about the ratio of the volume of sphere to the volume of the cube built on the sphere’s diameter? That’s π/6.

The area under the bell-shaped curve y=1/(1+x²) is π. But this curve isn’t actually the well-known and universal bell-shaped curve seen in statistics that has the formula y=e. The area under that curve is the square root of π! If you drop a pin of length one centimeter on a sheet of lined paper with lines spaced at centimeter intervals, the probability that the pin crosses one of the lines is 2/π. If you choose two whole numbers at random, the probability that they will have no common factor is 6/π².

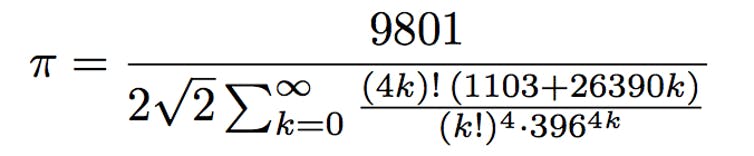

There are thousands of formulas for π of one sort or another, although it isn’t clear whether any of them will satisfy the desire to know what π is exactly. One such formula is

where the sigma symbol indicates that one must plug in all the whole numbers in place of the symbol “k” in the subsequent formula and add up the resulting infinitely many fractions. What is remarkable about this expression is that it was discovered by the legendary Indian genius Srinivasan Ramanujan in 1914, working alone. No one knows how Ramanujan came up with this amazing formula. Moreover, his formula wasn’t even shown to be correct until 1985—and that demonstration used high-speed computers to which Ramanujan had no access.

π Is Beyond Universal

The number π is a universal constant that is ubiquitous across mathematics. In fact, it is an understatement to call it “universal,” because π lives not only in this universe but in any conceivable universe. It existed even prior to the Big Bang. It is permanent and unchanging.

That’s why the celebration of Pi Day seems so silly. The Gregorian calendar, the decimal system, the Greek alphabet, and pies are relatively modern, human-made inventions, chosen arbitrarily among many equivalent choices. Of course a mood-boosting piece of lemon meringue could be just what many math lovers need in the middle of March at the end of a long winter. But there’s an element of absurdity to celebrating π by noting its connections with these ephemera, which have themselves no connection to π at all, just as absurd as it would be to celebrate Earth Day by eating foods that start with the letter “E.”

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Daniel Ullman is a professor of mathematics at George Washington University.