The Emissions Gap Report finds that the world is on track to overshoot emissions reduction targets in 2030—and blow past the two-degree warming limit.

By Kate Wheeling

A Chinese woman wears as mask while walking in a neighborhood next to a coal-fired power plant in Shanxi, China. (Photo: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images)

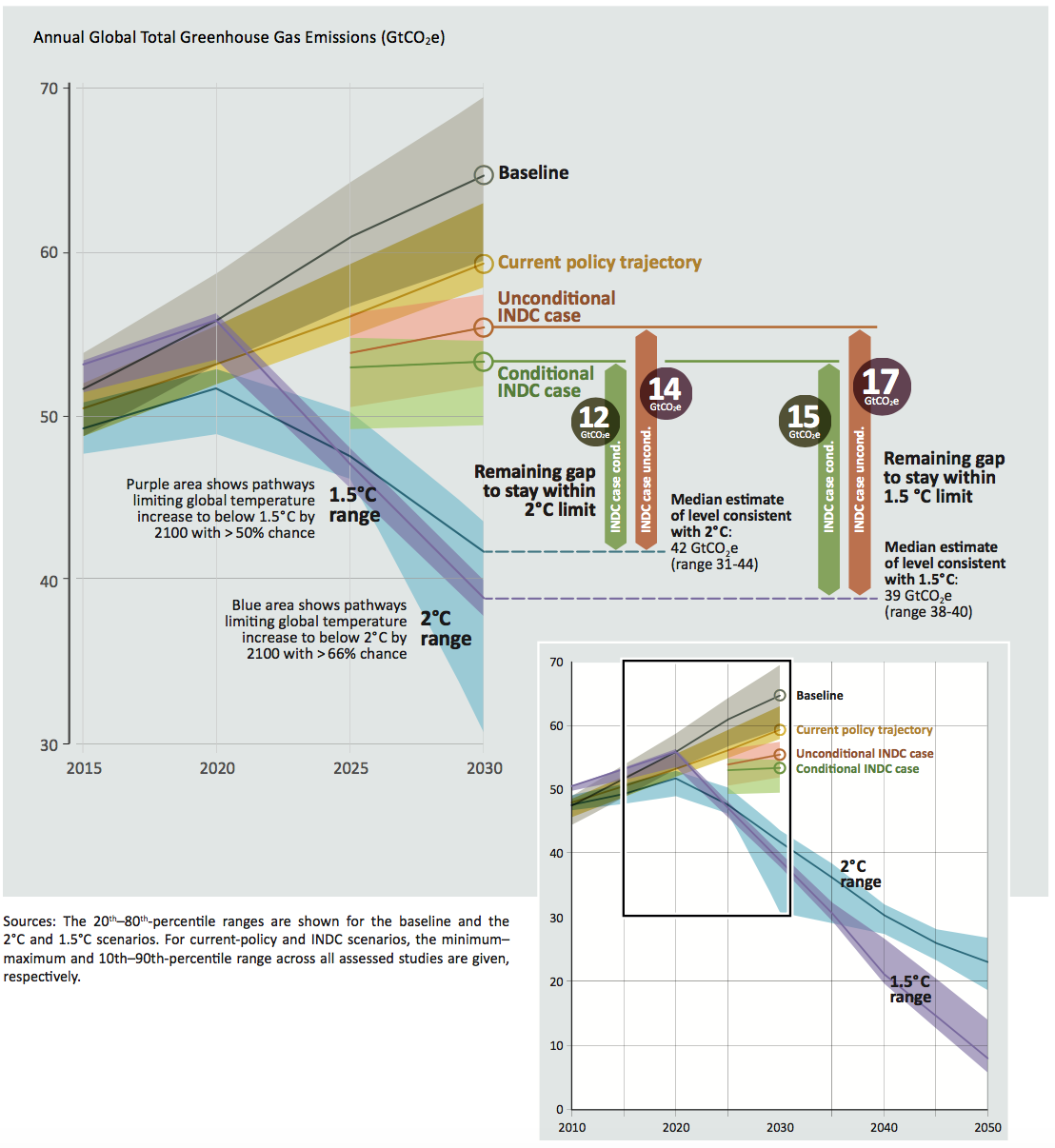

The day before the Paris Agreement enters into force, the United Nations Environment Program has released its annual Emissions Gap Report, which measures the discrepancies between likely emissions (based on climate policies and plans) versus the emissions levels necessary to limit warming. The outlook is bleak. To meet the goal of the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit warming below two degrees Celsius (and ideally below 1.5 degrees), we need to reduce global emissions to roughly 42 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2030.

The latest UNEP report suggests that, even in a best-case scenario, we could miss the mark by at least 12 gigatons.

Global greenhouse gas emissions have been climbing for decades, reaching 53 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2014. While the rate of increase of global emissions, and carbon dioxide emissions in particular, began to slow around 2012, it’s still too soon to tell whether the trend has permanently reversed. In fact, the new report suggests that, even if all of the Intended Nationally Determined Contributions submitted by Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change are implemented, global emissions are likely to remain about the same—or could increase even further.

The new report evaluates INDCs accounting for 187 of the 195 Parties to the UNFCC, and finds that, if they are fully implemented, emissions are likely to reach between 53 and 56 gigatons by 2030. Those emissions levels translate to a temperature increase of about three degrees Celsius by 2100. If both the conditional and unconditional aspects of all the INDCs are implemented by 2030, we’ll still miss the emissions mark by 15 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent, according to the UNEP.

Global greenhouse gas emissions under different scenarios and the emissions gap in 2030 (Source: The UNEP)

Many experts have previously acknowledged that the INDCs, at their current level of ambition, are inconsistent with the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goals. “The INDCs represent a very meaningful improvement compared to business as usual. Under business as usual, we were on track for warming on the order of four to five degrees. With the INDCs in place we’re looking at warming between 2.7 and 3.7 degrees depending on the estimate,” Taryn Fransen of the World Resources Institute says. “That’s a significant improvement, but obviously it’s not yet consistent with the global goal of 1.5 to two degrees, and that’s why the Paris Agreement adopted several mechanisms by which countries will need to increase the ambition of their targets over time.”

Parties submit new INDCs every five years, and the Paris Agreement stipulates that “each Party’s successive nationally determined contribution will represent a progression beyond the Party’s then current nationally determined contribution and reflect it’s highest possible ambition.”

For most countries, additional climate action beyond their current policies is necessary to meet the promises made in their INDCs, but the report notes that, in some countries, current policies could meet or exceed their INDCs. This suggests there may be some easy targets for strengthening INDCs, according to the report.

But the new Emissions Gap Report underscores the importance of immediate action. Most climate models that limit warming below two degrees involve the use of unproven and expensive technologies that actively remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere by the end of the century. Sharp decreases in emissions in the short term could help nations avoid the use of costly negative emissions technologies. Indeed, pre-2020 mitigation measures are likely the only way warming can be limited to 1.5 degrees, as most studies suggest that, to limit warming to that degree, carbon emissions have to peak around 2020.

“Due to the path-dependence of technology and the risk of lock-in, the earlier these targets are enhanced, the easier and less costly it will be to achieve them,” the report states. “The more ambitious early mitigation is, the less the world will have to rely on socially contested negative emissions technologies and high-cost emission reduction op ons in the future.”

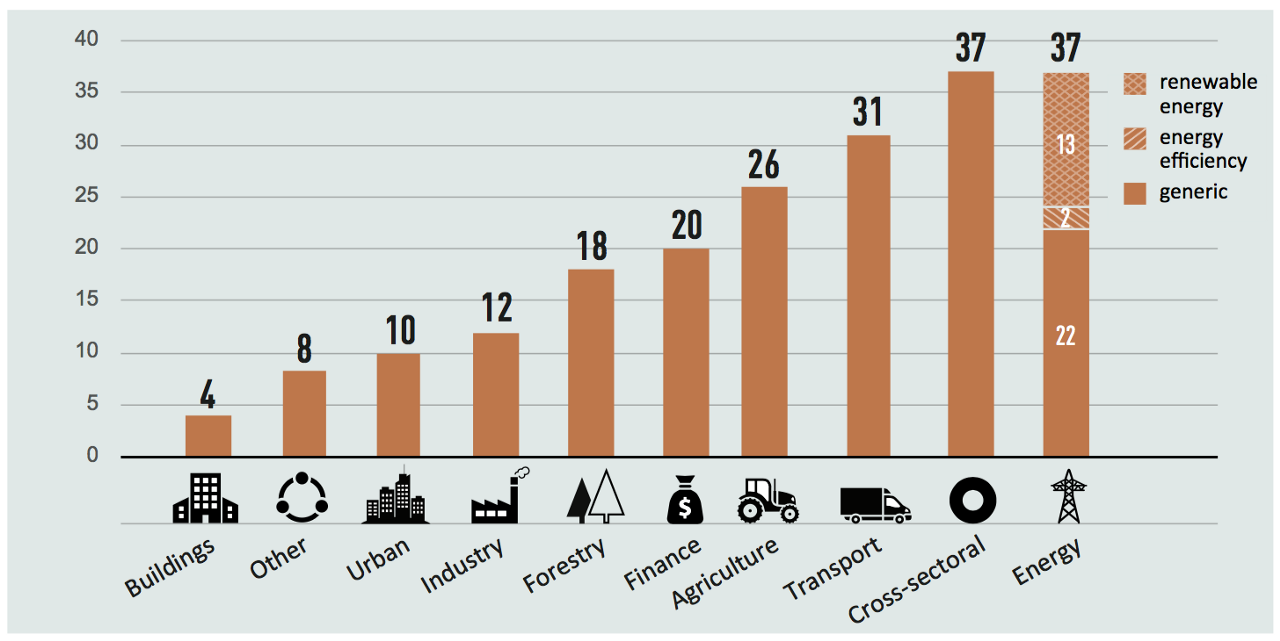

Climate action from so-called non-state actors — cities, citizens groups, and the private sector — could supplement INDCs, closing the gap by a few gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent. The number of such non-state climate initiatives has been growing for years; there are over 11,000 climate commitments from cities, companies, civil groups, and investors in the Non-State Actor Zone for Climate Action platform, which was launched just two years ago at COP20 in Lima. Energy efficiency gains in three key sectors — buildings, industry, and transport — is another area that can cut into the emissions gap. A conservative estimate of the emissions reduction potential suggests at least 5.9 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent from buildings could be saved, 4.1 gigatons for industry, and 2.1 for transport.

Distribution of non-state, mitigation-focused International Cooperative Initiatives by sector. (Source: The UNEP)

“You see a lot of media coverage around the Paris Agreement coming into force,” Harjeet Singh of ActionAid says. “It’s important for us to continue to highlight that the pre-2020 action is equally or probably more important, and we can’t lose sight of that.”