On Tuesday, at a factory in Kenosha, Wisconsin, President Donald Trump signed a new executive order calling for stricter enforcement of both the federal government’s “buy American” mandate and the rules governing the H-1B visa, the temporary, non-immigrant guest worker program. The order, which comes on the heels of several other changes to the H-1B visa program made earlier this month, also asks federal agencies to conduct a review of the H-1B visa program and propose their own reforms.

Trump lauded his order as a means of bringing back “the American dream.” But this isn’t all bluster on Trump’s part: The president’s targeting of the H-1B visa program may be among the most popular actions he’s taken so far.

The H-1B visa program was intended to enable companies to hire highly skilled foreign workers with specialized knowledge — think rocket scientists, world-class neurosurgeons, technology geniuses, etc. The idea is to target people with a skill set that employers couldn’t already find in the United States. If the program really worked like that, the economic arguments in favor of it would be pretty solid. The workers arriving in the country on these visas wouldn’t be “taking American jobs”; they would be filling jobs that couldn’t be filled by an American.

Unfortunately, that’s not how the program works. Somewhere along the line, companies started using the program to cut costs. The H-1B program has been plagued by accusations that companies (including Toys “R” Us, Disney, and Southern California Edison) are bringing guest workers into the country, teaching them to perform the jobs of American workers (while paying them less than those workers), sending those guest workers home to set up an outsourcing operation, and eventually firing the now-redundant American workers.

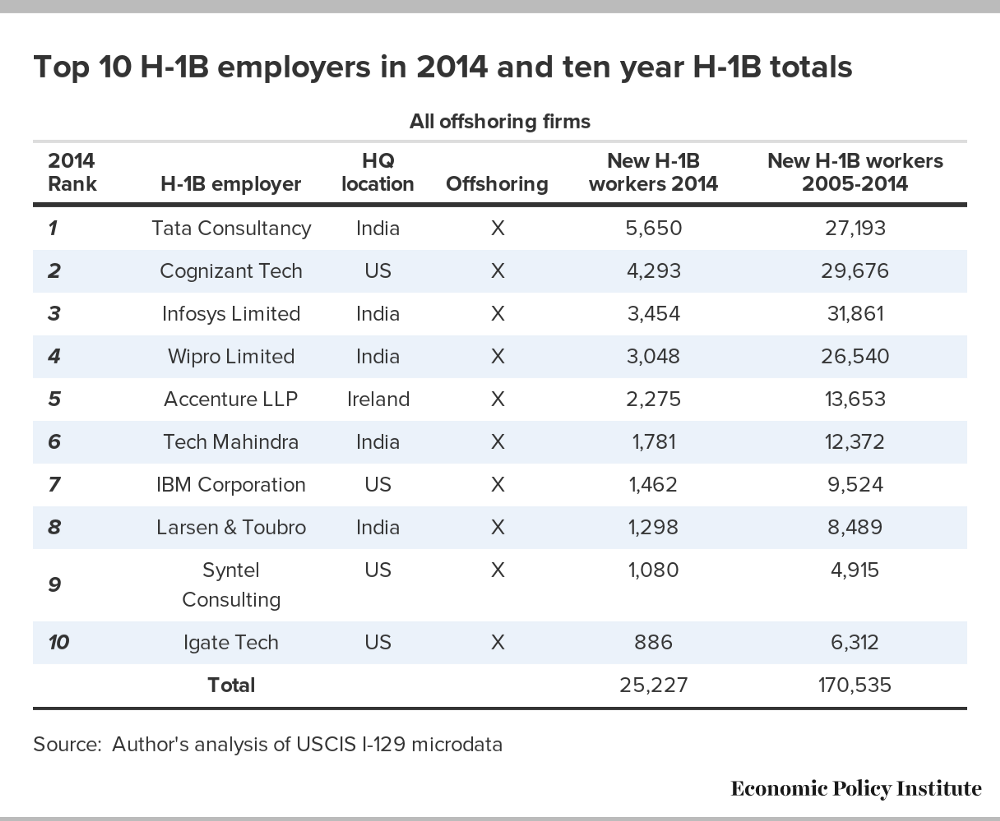

The chart below, fromRon Hira of the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal think tank, lists the top 10 H-1B employers:

All of these companies are, in Hira’s words, “leaders in using the offshore outsourcing business model to sell information technology (IT) services.”

There’s quite a bit of evidence to suggest that at least some of these companies are using these visas in a way that doesn’t align with the program’s intent. If the recipients of H-1B visas were indeed highly skilled, we would expect them to be well-paid. But as this chart (also from the EPI) shows, Infosys and Tata Consultancy, consistently two of the biggest users of the program, pay H-1B visa workers less than we’d expect:

Nor do the workers hired by Infosys and Tata seem to be especially well-educated. Here’s Hira again:

Are H-1B workers being brought in because they have extensive formal training, like an advanced degree? The answer to that is a definitive no. The vast majority of Infosys and Tata’s imported H-1B workers hold no more than a Bachelor’s degree. During the FY10–12 period, 78 percent of Tata’s and 85 percent of Infosys’s H-1B employees held only a Bachelor’s degree or less. Finally, there’s also no evidence that Tata and Infosys are using the H-1B to retain foreign students who studied and earned an advanced degree in the United States: Only 1-in-206 of Infosys’ H-1B workers held an advanced degree from a U.S. university, and even less of Tata’s H-1B workers did, just 1-in-222.

The available academic research also raises alarm bells about whether the program is being abused. In a working paper published earlier this year by the National Bureau of Economic Research, economists John Bound, Gaurav Khanna, and Nicolas Morales looked at the effects of the H-1B visa program on consumer welfare and the wages and employment of U.S. computer scientists between 1994 and 2001.

They found that, while consumers benefited from lower prices on IT goods, employment of U.S.-born computer scientists declined.

“In the absence of immigration, wages for US computer scientists would have been 2.6% to 5.1% higher and employment in computer science for US workers would have been 6.1% to 10.8% higher in 2001,” the economists concluded. “On the other hand … immigration also lowered prices and raised the output of IT goods by between 1.9% and 2.5%, thus benefiting consumers. Finally, firms in the IT sector also earned substantially higher profits due to immigration.”

In its current form, the H-1B visa program isn’t particularly popular, and members of both political parties have called for reform. Some tech companies (i.e. Google) also want reform as it’s become increasingly difficult to obtain visas for genuinely skilled workers (the program has essentially operated as a lottery in recent years, advantaging the companies that place more applications). Even immigration advocates don’t love the program because its structure leaves guest workers vulnerable to exploitation by their employers.

There are a lot of really good economic (not to mention moral) reasons to support immigration, and eliminating the program entirely would serve no one. Trump, however, is correct: The H-1B visa program is due for a revision.