(Photo: Brendan Smialowski/Getty Images; Pacific Standard)

When questioned on immigration, Donald Trump returned to his usual trope of building a wall to prevent drugs and crime from flowing from Mexico into the United States. It is, of course, “a mess,” in his viewing.

But, according to the data, not so much: President Barack Obama has overseen one of the highest upticks in border enforcement and deportment in modern American history. As I wrote in September:

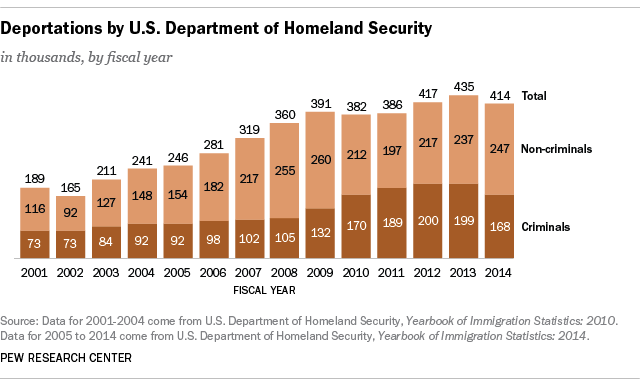

Despite accusing President Barack Obama of being lax on immigration, the current administration spent a record $18 billion on immigration enforcement in 2012, more than all other federal law enforcement agencies combined (per the New York Times). By the end of 2013, deportations reached a record high of 438,421 unauthorized immigrants, according to the Pew Research Center; while that number dropped 5 percent the next year, the Obama administration has still deported a total of 2.4 million between 2009 and 2014.

(Chart: Pew Research Center)

Clinton’s riposte to Trump — a pledge to introduce comprehensive immigration reform within her first 100 days in the White House — actually gets more to the heart of the real crisis at the border: That undocumented immigrants, especially children, often suffer in a bureaucratic limbo before they’re processed and, often, deported. As I wrote:

Children are either thrown into a short-term border control holding facility or sent to U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement shelter. In the case of the former, these children are often placed in foster care or released to sponsors, few of whom are appropriately vetted. Home studies of sponsors are only conducted in fewer than 5 percent of cases, per Child Trends, and a 2016 report by the Department of Health & Human Services revealed “allegations of sexual misconduct by contract staff in [ORR] contracted facilities, extortion scams of ORR sponsor families, and the potential for grant fraud.” …

While undocumented migrant children must be referred to an immigration court within three weeks of their apprehension at the border, Child Trends reveals that the average filing for a hearing day is nearly 700 days, or almost two years, after. That’s a significant increase from the 100-day waiting period the Office of Inspector General uncovered back in 2012, itself far beyond the department’s 60-day “timeliness” limit.

Compassion, not suspicion, can fix the real crisis at the border.