A white man arrested for threatening to bomb a Muslim-majority town avoided terror charges. In all likelihood, he won’t be the last.

By Jared Keller

(Photo: Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

In April of 2015, Robert Doggart was arrested for allegedly planning to destroy a mosque in the town of Islamberg, New York. While he lacked weapons, the New York Daily Newsreports that Doggart “allegedly went on right-wing online forums and openly talked about using AR-15 assault rifles to attack Muslims because he believed the small upstate community was an extremist training camp.” Despite Doggart’s convictions, there is no evidence to suggest that Islamberg, a Muslim-majority community founded in the 1980s, has ever harbored terrorism. It was Doggart’s Internet activity that led to his arrest by New York law enforcement.

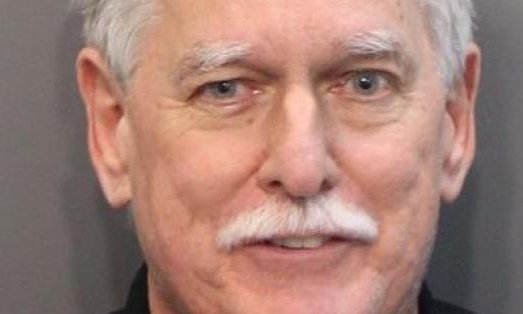

But Doggart, a 65-year-old Tennessee man, isn’t necessarily classified as a terrorist in the eyes of the law.

While Doggart was found guilty on Thursday of planning to attack Islamberg (the charges included “one count of solicitation to commit a civil rights violation, one count to commit arson of a building, and two counts of threat in interstate commerce”), he escaped without being branded as a domestic terrorist. The Daily News reports that he’ll escape terror charges thanks to “a gap in the law,” as attorney Tahirah Amatul-Wadud told the paper: “[T]here is nothing on terrorism unless it’s connected to a foreign element. You won’t see the KKK charged with domestic terror even though that’s what they do.”

This isn’t the first time the issue of labeling domestic terrorism as “terrorism” rather than a hate crime or a lesser infraction has come up in recent years. As I noted in the aftermath of the Charleston church massacre, the Federal Bureau of Investigation has a very specific definition of domestic terrorism: It involves “acts dangerous to human life that violate federal or state law,” which appear “intended to intimidate or coerce a civilian population,” and “occur primarily within the territorial jurisdiction of the U.S.” Ironically, the Patriot Act passed in the aftermath of 9/11 that created this (relatively expanded) definition of domestic terrorism has been criticized by civil rights groups like the American Civil Liberties Union for being dangerously broad, broad enough to include more aggressive activist groups (namely Greenpeace, as the ACLU points out). That definition isn’t broad enough to encompass people like Doggart, who “tend to be charged with conspiracy, organized crime, and weapons violations,” the Southern Poverty Law Center told the BBC.

Robert Doggart. (Photo: Hamilton County Jail)

That double standard on terrorism is deeply entrenched in American society. A late-2015 Public Religion Research Center poll conducted in the aftermath of the deadly Paris attacks found that Americans tend to think of religious extremism, for example, as a primarily Muslim problem: Seventy-five percent of respondents believed Christian terrorists “are not really Christian,” but only 50 percent said self-identified Muslim terrorists “are not really Muslim.” Similarly, Americans tend to automatically label Muslim mass murderers as “terrorists,” while white Christian shooters tend to like a “lone wolf” in the public’s mind. When the threat is brown or black, whether a foreign terrorist or anti-police activist, Americans put their hackles up; when it’s white, not so much.

What was once primarily a cultural bias is swiftly becoming official policy at the hands of President Donald Trump, and not just through his immigration executive order. Earlier this month, Reuters reported that the Trump administration planned on repurposing a government program meant to neutralize all types of violent ideologies to zero in on Islamic extremism: “Countering Violent Extremism” will quite literally become “Countering [Radical] Islamic Extremism.” The irony, of course, is that CVE pilot programs and community grants launched in Boston, Los Angeles, and Minneapolis during the Obama administration tended to disproportionately focus on Muslims anyway, according to a 2015 report by the Brennan Center for Justice; Trump merely baptized America’s cultural biases with a name.

This is unsurprising. In the waning years of the Obama administration, Congress refused a $2 million funding request for the Department of Justice’s State and Local Anti-Terrorism Training Program that, created in 1966, has kept tens of thousands of law enforcement officers ready to deal with domestic terror threats. Consider that Steve Bannon, who in the last few years has warned of the prospect of a religious war between the West and Islam, mocked the prospect of right-wing terrorism on a Breitbart News Daily segment this past April. Consider the 27-year-old Canadian student accused of murdering six civilians in a Quebec City mosque — who was reportedly a devotee to far-right and anti-immigrant causes, but was initially portrayed as a Moroccan Muslim by right-wing media. White House press secretary Sean Spicer used the incident to justify the president’s immigration ban.

This single-minded obsession with the specter of Islamic terror couldn’t come at a worse time: According to a new report by the SPLC, right-wing extremism was “more successful in entering the political mainstream last year than in half a century.” The number of hate groups operating in the United States jumped to a high of 917 in 2016, from 892 in 2015 (although both remain below the historic peak of 2011), with a particularly pronounced increase (197 percent) among anti-Muslim hate groups; indeed, hate crimes against Muslims spiked in the first month after Election Day. Until the 2016 attack on the Pulse nightclub in Orlando that left 49 dead, right-wing extremists took far more American lives than Islamic terrorists in the years after 9/11, according to a count by the New America Foundation. And a survey of more than 350 law enforcement groups by the Triangle Center on Terrorism and Homeland Security found that the majority considered “anti-government violent extremists, not radicalized Muslims, to be the most severe threat of political violence that they face.”

Doggart wasn’t the first far-right extremist to come out of the woodwork this election cycle: In October, three militiamen affiliated with a group called “The Crusaders” were charged with conspiring to bomb a Kansas apartment complex on Election Day that was home to more than 100 Somali-Muslim refugees. By focusing on solutions for problems that don’t exist, Trump might miss the real threat growing at home — because Doggart and the Crusaders likely won’t be the last.