Koren Carbuccia is an employment specialist in Pawtucket, R.I., a busy mother of an inquisitive 6-year-old and an ex-felon. Carbuccia served two sentences in Rhode Island for dealing and possession of cocaine. She is on probation until 2017. Until recently, she couldn’t vote under Rhode Island law, which considers the probation to be part of her felony sentence.

“I keep my head high when I walk down the street because I know I’m an honest person today. But there’s always that back feeling,” Carbuccia says. “It’s just another shot down at me, trying to do the better and the right thing.

“Like, ‘You still can’t (vote).’

“‘But I paid my dues.’

“‘You still can’t.'”

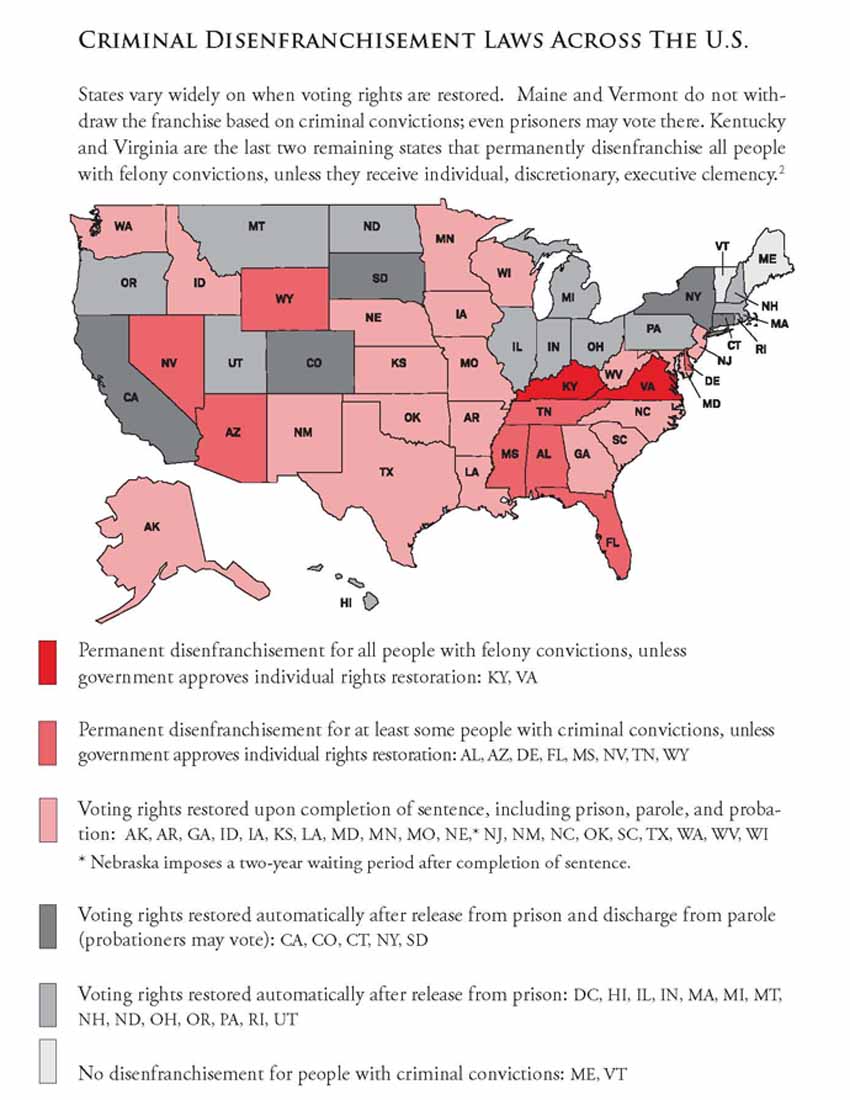

Across the United States, more than 5 million people cannot vote because of a felony conviction, according to estimates by the American Civil Liberties Union and The Sentencing Project, a criminal justice advocacy and research nonprofit. In almost every state, people who go to prison lose the right to vote while there. Whether they can vote when they get out of prison depends on their location. Of the more than 5 million people who can’t vote because of a felony conviction, about 4 million are outside prison.

Some states keep ex-felons from voting for the rest of their lives. Other states restore voting rights at the prison door. Some require cumbersome restoration procedures. In Mississippi, a formerly incarcerated person would have to get the Legislature to pass a personal bill to get the right to vote back. In some 20 states, ex-felons cannot vote if they are still on parole or on probation. And terms of parole or probation could last a few months or many years. In some states, convicted sex offenders and people released from life prison sentences can be placed on parole for the rest of their lives.

The variation in how states deal with voting rights and felons creates real-life problems, says Erika Wood, director of the Right to Vote Project at the Brennan Center for Justice, a legal research institute based at the New York University School of Law.

“If you’re convicted in New York and you retire to Florida, like so many people in New York do, do you have the right to vote or not? You know laws are different in each state, and how does that play out?” Wood asks.

In the past decade, more than a dozen states, including Florida, New Mexico and Maryland, have made changes to their voting laws to extend the franchise to ex-felons. In 2006, voters approved an amendment to Rhode Island’s constitution to allow 15,000 people on parole and probation to vote. Koren Carbuccia was one of them. “When it happened, it was overwhelming for me, and I couldn’t wait to run home and hug my son,” Carbuccia says. “I mean we changed history.”

It’s unclear if or when history might change in the same way across the nation.

In February, U.S. Sen. Russ Feingold, D-Wis., co-wrote an op-ed for The (Baltimore) Sun, announcing that he will introduce a bill, the Democracy Restoration Act, to allow every non-incarcerated person in the U.S. to vote in federal elections. He called post-incarceration loss of the voting franchise “civil death” and a national problem that harms democracy.

There have been other efforts to restore federal voting rights to ex-felons; U.S. Rep. John Conyers, D-Mich., has repeatedly introduced bills on the subject, often in cooperation with voting rights organizations. The Brennan Center’s Wood says the effort continues because ex-felon voting prohibitions are fundamentally wrong. “This is America, and we don’t decide who gets to vote based on if we think they deserve to vote,” she says. “American citizens should have the right to vote.”

But the question is hardly cut and dried, in the legal or the ethical sense, and it is absolutely suffused with politics. The felon voting bills and amendments haven’t passed in large part because they have failed to draw Republican votes.

U.S. Sen. Jeff Sessions, R-Ala., opposed an amendment in 2002 that would have given all ex-felons the right to vote in federal elections. “Frankly, I do not think the American debate and American policy is going to be better informed if we have a bunch of felons in this process, as opposed to them not being in this process,” he said.

Sessions and many other Republicans contend that Congress doesn’t have the authority to alter voting regulations. Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., concurred and, during the same Senate debate, added that “voter qualification is generally a power the Constitution leaves within the prerogative of the states. The Constitution grants states broad power to determine voter qualification.”

Beyond politics are the legal arguments for stripping felons of voting rights.

Voting may be a right granted to every American who is 18 or older, but society deprives people who have been convicted of serious offenses of all kinds of rights, says John Lott, a researcher at the University of Maryland and the author of More Guns, Less Crime: Understanding Crime and Gun Control Laws and Freedomnomics: Why the Free Market Works and Other Half-Baked Theories Don’t. “We lock them up,” he says. “We deprive them of liberty.”

And don’t allow them to vote.

Public opinion polls show that few Americans support voting rights for people serving a prison sentence, and only two states, Maine and Vermont, allow felony prisoners to vote. Massachusetts used to allow inmates to vote — until a few prisoners attempted to form a political action committee in 1997. Then-Gov. Paul Cellucci, a Republican concerned that inmates might organize to fight the laws that put them in prison, proposed a state constitutional amendment to curb the prisoner vote. The Democratic state Legislature approved the amendment in 2000.

Lott says other officials should be concerned about the motivations of ex-felons in the voting booth. “Is that clear, that you want those types of people to make decisions on who’s going to be a sheriff or what types of law enforcement activity they’re going to be having in a particular area?” Lott asks.

Just the same, there is increasing clamor to give ex-felons the right to vote. Most of the noise has been made by Democrats, in no small part because voting restrictions on felons disproportionately affect African Americans and Hispanics, who tend to vote overwhelmingly Democratic.

Since ancient Greece, societies have taken away the voting rights of citizens who commit heinous crimes. But slaves and women couldn’t vote in ancient Greece, and now most European Union countries allow all or some inmates to vote from prison. Of the EU nations that take the vote away from prisoners, few continue the prohibition post-incarceration.

Voting-rights advocates like Wood say laws that strip felons of the vote are vestiges of systemic racism. Even though some states have had felon and ex-felon voting statutes on the books since the founding of the country, many others instituted restrictions during the post-Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras. The object: to suppress the black vote.

“Just like literacy tests and poll taxes,” Wood says, “they for the most part targeted offenses that lawmakers thought freed slaves were most likely to commit.”

Felon-disenfranchising laws still disproportionately affect black people and Latinos because members of those groups are locked up for felony crimes at higher rates than whites and other racial groups. The Sentencing Project estimates that some 13 percent of black men in America have lost their voting rights. And in certain majority-black communities, the number is higher. Before Rhode Island changed its laws, in parts of the capital, Providence, nearly 40 percent of black men couldn’t vote because of a conviction.

The implications for black and brown communities are huge, says Juan Cartagena, a civil rights lawyer and the general counsel for the Community Service Society in New York, an organization that works on poverty issues.

“Felon disfranchisement affects not only the individual whose vote has been taken away; it’s not just what voting-rights lawyers call a vote-denial claim. It’s also a vote-dilution claim,” Cartagena says. “That relative political power is taken away from the neighbors of persons who come back home (and) from their family members. Their relative collective voting strength is wiped off the map almost.”

So the argument comes back to whether the government can deny basic rights to citizens who are deemed unfit, including people in prison and people who have been released from prison, especially if the denial has a disproportionate effect on the voting power of a minority group. In fact, several different voting-rights lawsuits have been filed in federal court in recent years.

Court cases in Washington, New York, Florida, Massachusetts and New Jersey have challenged felon disenfranchisement laws as discriminatory and, in some instances, as violations of the Voting Rights Act. The cases have largely been dismissed. Voting-rights advocates refuse to concede defeat and continue their appeals. The Supreme Court has repeatedly declined to review the issue.

Curran white of Newark, N.J., did three stints in prison and spent much of his 20s and 30s cycling through the penal system. After his last sentence — for felony possession of marijuana, cocaine and heroin — he was determined to do everything right: go to school, keep up with his parole officer and become an honest-to-God taxpaying citizen. And, for that, he needed a job, any job. Well, any legal job.

“I need some type of finances coming in; otherwise I’ll be right back where I started from, and that’s not a pretty place to be,” White says.

Omar Shabazz coordinates the Prisoners Resource Center, a re-entry project of the American Friends Service Committee in Newark. He says the prison revolving door spins fast because society deprives ex-felons of so many rights. “Right now they are sending people out here who don’t have a job, don’t have food, don’t have clothing, don’t have family,” Shabazz says. “They give them a fishnet bag with some books and papers they had in prison and turn them loose on society.”

And maybe that’s a reason we might actually want ex-felons to vote, Shabazz says. He is also an ex-felon, on lifetime parole. If he and Curran White and all the people he knows on long parole or probation sentences could vote, Shabazz says, politicians might pay attention.

“If you had this voting bloc and say we’re going to support this group here because they’re going to have free meals for all the people that come home from prison. Or they gonna address the mandatory minimums in sentencing or address discrimination in hiring practices for the ex-offender population,” Shabazz says. “So, there’s a lot of things, if you had the vote, politically, that you would ask the legislators — whether it be the mayor, the councilman, the senator — to come up with some programs for this population that’s coming home after serving time and paying their debt to society.”

According to a recent Pew study, 1 in 100 Americans is in prison. Thirteen states restore voting rights upon release from prison. If the Democracy Restoration Act passes, it will change the law for federal elections in New Jersey and 34 other states all at once. Omar Shabazz’s hypothetical vote would become a reality.

And whether you view that as good or bad may depend as much on your politics and race as on anything else.

(Image from “Restoring the Right to Vote,” by Erika Wood, Brennan Center for Justice, New York University School of Law)

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Click here to become our fan.