The head of Goldman Sachs is scared.

Speaking to CNBC’s Squawk Box last week during the aftermath of Hillary Clinton’s razor thin victory over Bernie Sanders in the Iowa caucuses, Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein conceded that the Vermont senator’s insurgent candidacy “has the potential to be a dangerous moment.”

“It has the potential to personalize it, it has the potential to be a dangerous moment,” Blankfein said of Sanders’ fiery rhetoric directed toward America’s billionaire class. “Not just for Wall Street, not just for the people who are particularly targeted, but for anybody who is a little bit out of line. It’s a liability to say I’m going to compromise I’m going to get one millimeter off the extreme position I have and if you do you have to back track and swear to people that you’ll never compromise. It’s just incredible. It’s a moment in history.”

Beneath Blankfein’s salvo at Sanders is an element of fear—and it’s not unjustified. The up-and-coming class of Millennial consumers whose behaviors will fundamentally shape the economy don’t trust established institutions, let alone the stock market. This is a big deal, considering that 71 percent of Millennials would change their vote if a candidate doesn’t meet their position on financial regulation, according to a 2015’s poll from Harvard University/IOP—the same poll that showed Wall Street is trusted less than any other major political or economic institution except for the media. While Clinton dominated the Iowa caucus among Democratic voters on issues like health care, terrorism, and jobs, Sanders outperformed on income inequality among 61 percent of voters. The senator, who has run his campaign almost entirely on individual contributions, has come to represent a symbolic rebuke of the monied politics unleashed by Citizens United.

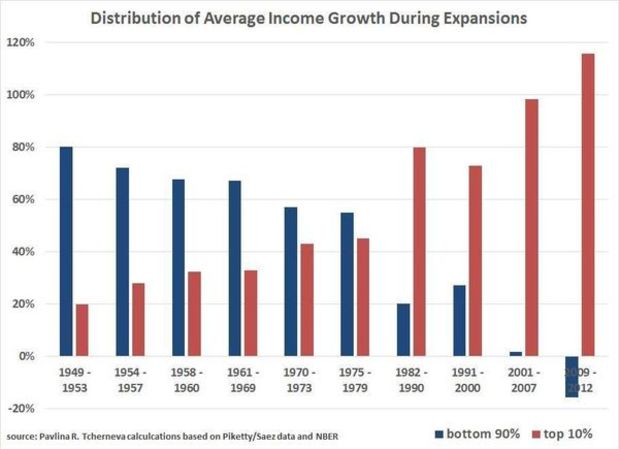

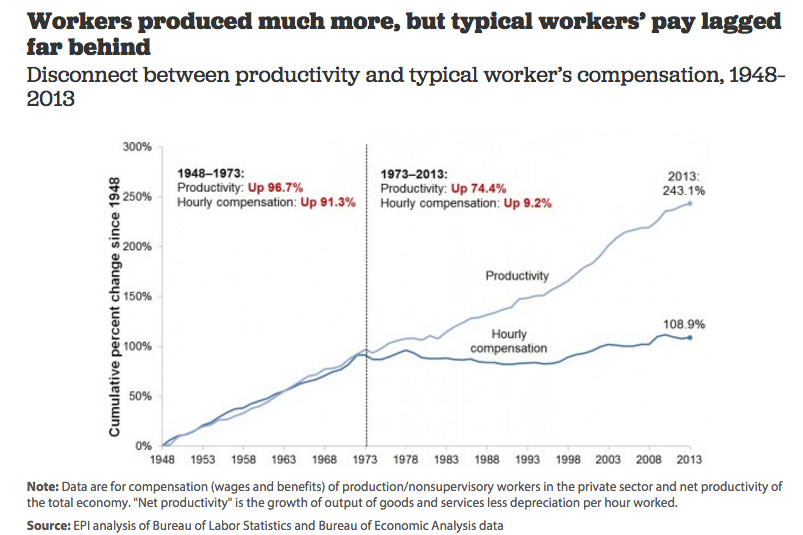

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that Wall Street, because of and in spite of its political clout, has become one of the most loathed sectors of American society. Most major financial institutions like Goldman Sachs haven’t just escaped prosecution by the Department of Justice for their hand in the housing crisis that precipitated the Great Recession; they’ve also monopolized the gains of the resulting recovery. Meanwhile, average income growth has become increasingly concentrated in the hands of the top 90 percent of earners; wealth has become increasingly concentrated in the hands of the super rich; and wages remain stagnant for the middle-class workers not already left behind by the decimation of America’s manufacturing sector. We live in a world where 62 people own as much wealth as half the planet and the United States has the worst income inequality of any developed nation.

While the electorate feels the economic effects, American greed is made manifest in the culture by the likes of Donald Trump and Martin Shkreli, both of whom see themselves simply as products of a system, apparently oblivious to the moral treachery they are complicit in.

Consider this mind-boggling quote from Steven Schwartzman, the billionaire CEO of private equity giant Blackstone, at the annual confab of economic elites in Davos this year: “I find the whole thing astonishing, and what’s remarkable is the amount of anger, whether it’s on the Republican side or the Democratic side. Bernie Sanders, to me, is almost more stunning than some of what’s going on in the Republican side. How is that happening, why is that happening?”

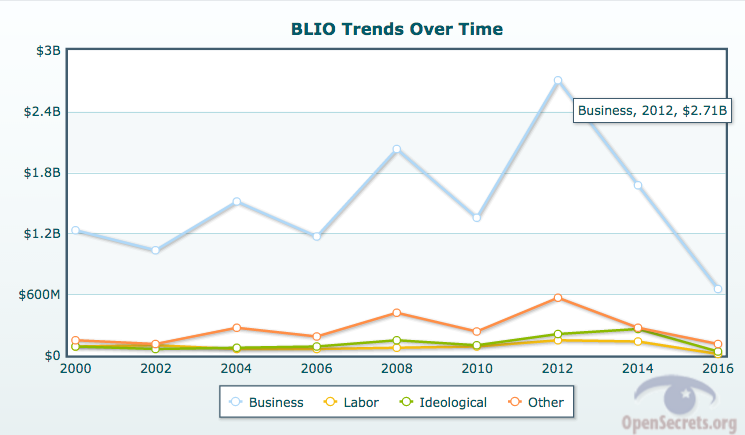

This is the more acute political anxiety underlying the dread felt on Wall Street. The eventual victory of Clinton or really any moderate Republican candidate would offer a relatively safe respite from the political backlash to the disparate economic gains made under President Obama’s administration. And this sense of predictability, an econometric certainty that analysts love, is bought and paid for by Wall Street; business interests have donated some $654.7 million already this cycle, far more than any other individual or PAC affiliation. Goldman Sachs alone has already forked over some $4.7 million in donations to both Republicans and Democrats this election cycle, while Clinton herself received a total of $675,000 from the investment bank for three speeches. The same day Blankfein aired his anxiety on Squawk Box, Clinton reminded the country who she really works for: When asked of her speaking fees at the Democratic Town Hall on Wednesday, Clinton responded with “that’s what they offered.” No wonder Wall Street loves Clinton.

This is the problem that Sanders’ insurgent campaign poses for Wall Street. While a Sanders presidency would almost immediately lead to gains in the House and Senate during the 2018 mid-terms (assuming the GOP follows the same playbook as the 2010 Tea Party backlash to Barack Obama’s “socialism,” which they might given the current ideological composition of the Republican caucus), his momentum as a populist candidate poses more of a threat to the current American ecosystem. “Markets don’t like uncertainty, and the more extreme the candidates that get nominated the greater the uncertainty,” JPMorgan Funds chief global strategist David Kelly told CNBC as oil declined and stocks dropped following the Iowa caucus. “The fact that on the Democratic side, a more centrist candidate won, although narrowly, and on the Republican side, there was a swing toward a more centrist candidate. I think in both those cases, those things would be regarded as market friendly.”

Sanders isn’t “market friendly” because Sanders is an enemy of the status quo, and that’s terrifying to executives at Goldman, JP Morgan, and BlackRock who have had free run of the place. But the “dangerous moment” that Blankfein referred to isn’t just a short-term drop in a stock market Millennials don’t care about. A Sanders candidacy, even a Sanders insurgency that’s more an ideological test balloon than it is a realized political revolution, is terrifying, especially as the biggest investors on Wall Street are fundamentally questioning the inner workings of capitalism.

The same Wednesday that Blankfein and Clinton tipped their hands on Wall Street, a memo surfaced from Goldman Sachs saying that the soaring profit margins enjoyed by banks indicate a reckoning on the horizon. “We are always wary of guiding for mean reversion,” the note reads, per Bloomberg’s Joe Weisenthal. “But, if we are wrong and high margins manage to endure for the next few years (particularly when global demand growth is below trend), there are broader questions to be asked about the efficacy of capitalism.”

The system is broken, and Wall Street knows it—and it’s terrified that Sanders is actually going to fix it.