The Liberal Party won a surprise victory in Canadian elections last week, sweeping Justin Trudeau into 24 Sussex Drive. (That’s Canadian for “10 Downing Street.”) The victory has given hope to environmentalists and others worried about climate change.

The new prime minister could hardly be worse than his predecessor, Stephen Harper, who was a quote machine for climate change denial: The Kyoto Accord, he said, was based on “contradictory evidence about climate trends” and argued that we shouldn’t focus on carbon dioxide because it is “essential to life.” He tried to silence government scientists on the matter and called climate-based regulations on oil and gas “crazy.”

Trudeau, on the other hand, accepts the reality of climate change, making him an immediate upgrade on Harper. But he’s not Al Gore either. His proposals are nuanced and, in some cases, opaque.

The country will almost certainly miss its 2009 commitment to reduce carbon emissions 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2020—in fact, Canada’s emissions are on track to grow.

Take tar sands, for example. Miners in northern Alberta are digging up the world’s most carbon-intensive fossil fuel, contributing to the destruction of both the local environment and the global climate. The Harper government took a series of actions to facilitate expansion of the mines. Over the objection of prominent scientists, Harper removed habitat protections from the Canadian Fisheries Act. He stuffed the National Energy Board, which regulates pipeline companies, with oil executives and tried to rush projects along with little public input. Trudeau has repudiated those decisions and says he wants environmental assessments to include climate concerns.

What’s complicated, however, is Trudeau’s position on pipelines, a sine qua non of tar sands. Rail transport makes the already expensive Canadian crude completely uneconomical, so the industry is heavily reliant on the constant expansion of the pipeline network. Trudeau opposes the Northern Gateway pipeline on the grounds that it will increase shipping traffic in the sensitive intercoastal waters of British Columbia. But he backs the controversial Keystone XL, which is designed to funnel tar sands to the refineries on the United States Gulf Coast.

Days before the election, it emerged that David Gagnier, co-chair of Trudeau’s national campaign, had been advising KXL builder TransCanada on how to lobby the Quebec government. Although Gagnier quickly resigned, the incident is worrying.

“It would be a mistake to believe that Trudeau is the mirror opposite of Harper on tar sands expansion,” says Anthony Swift, director of the Natural Resource Defense Council’s Canada program. “He has left himself room to be progressive, but he could also tack right toward Harper’s positions.”

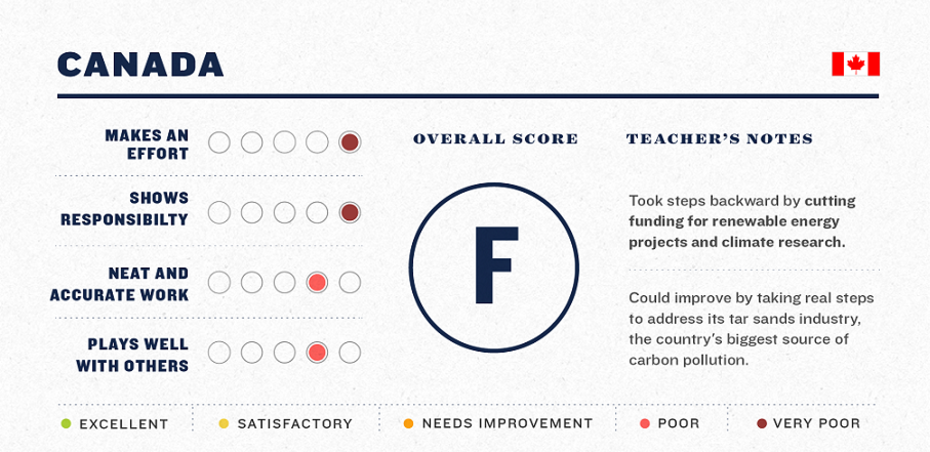

Trudeau’s approach to the global movement to cut carbon emissions is also unclear. Canada became something of an international climate pariah under Harper. The country will almost certainly miss its 2009 commitment to reduce carbon emissions 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2020—in fact, Canada’s emissions are on track to grow. Harper’s carbon pledge in anticipation of next month’s climate summit in Paris is also disappointing, as the country is no longer projected to meet its long-term targets and has abandoned its policy to keep in step with U.S. reduction commitments. (Click here to see why the NRDC gave Canada an “F” for its carbon commitment.)

Trudeau’s Liberal Party platform supports the international goal to limit global warming to two degrees Celsius, but Trudeau himself has said very little about how Canada will contribute. He hasn’t announced any carbon pollution targets, leaving open the possibility that he could stick to or even weaken Harper’s commitment. The little that Trudeau has said on the topic suggests his motivation on climate policy is to get the country away from its outcast status and aid the economy, not necessarily to improve the environment.

Fundamentally, the election was a referendum on the Harper government. Pre-election polling showed major swings between the more environmentally friendly New Democratic Party and the Liberals, apparently as voters shifted their opinions based on which side was more likely to amass enough support to unseat the incumbent. For that reason, Trudeau was able to leave many of his positions—particularly his views on climate change and tar sands—surprisingly vague.

The incoming prime minister’s window for obfuscation is now over. His first couple of months will reveal whether he’s ready to move Canada toward a clean energy future or stay stuck in the tar.

This story originally appeared on Earthwire as “Is Justin Trudeau Canada’s Climate Savior?” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.